An article published by The Conversation is offered today.

ooOOoo

Jane Goodall, the gentle disrupter whose research on chimpanzees redefined what it meant to be human

Charles Sykes/Invision/AP

Mireya Mayor, Florida International University

Anyone proposing to offer a master class on changing the world for the better, without becoming negative, cynical, angry or narrow-minded in the process, could model their advice on the life and work of pioneering animal behavior scholar Jane Goodall.

Goodall’s life journey stretches from marveling at the somewhat unremarkable creatures – though she would never call them that – in her English backyard as a wide-eyed little girl in the 1930s to challenging the very definition of what it means to be human through her research on chimpanzees in Tanzania. From there, she went on to become a global icon and a United Nations Messenger of Peace.

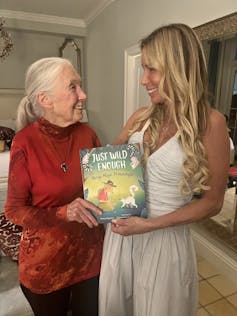

Until her death on Oct. 1, 2025 at age 91, Goodall retained a charm, open-mindedness, optimism and wide-eyed wonder that are more typical of children. I know this because I have been fortunate to spend time with her and to share insights from my own scientific career. To the public, she was a world-renowned scientist and icon. To me, she was Jane – my inspiring mentor and friend.

Despite the massive changes Goodall wrought in the world of science, upending the study of animal behavior, she was always cheerful, encouraging and inspiring. I think of her as a gentle disrupter. One of her greatest gifts was her ability to make everyone, at any age, feel that they have the power to change the world. https://www.youtube.com/embed/rcL4jnGTL1U?wmode=transparent&start=0 Jane Goodall documented that chimpanzees not only used tools but make them – an insight that altered thinking about animals and humans.

Discovering tool use in animals

In her pioneering studies in the lush rainforest of Tanzania’s Gombe Stream Game Reserve, now a national park, Goodall noted that the most successful chimp leaders were gentle, caring and familial. Males that tried to rule by asserting their dominance through violence, tyranny and threat did not last.

I also am a primatologist, and Goodall’s groundbreaking observations of chimpanzees at Gombe were part of my preliminary studies. She famously recorded chimps taking long pieces of grass and inserting them into termite nests to “fish” for the insects to eat, something no one else had previously observed.

It was the first time an animal had been seen using a tool, a discovery that altered how scientists differentiated between humanity and the rest of the animal kingdom.

Renowned anthropologist Louis Leakey chose Goodall to do this work precisely because she was not formally trained. When she turned up in Leakey’s office in Tanzania in 1957, at age 23, Leakey initially hired her as his secretary, but he soon spotted her potential and encouraged her to study chimpanzees. Leakey wanted someone with a completely open mind, something he believed most scientists lost over the course of their formal training.

Because chimps are humans’ closest living relatives, Leakey hoped that understanding the animals would provide insights into early humans. In a predominantly male field, he also thought a woman would be more patient and insightful than a male observer. He wasn’t wrong.

Six months in, when Goodall wrote up her observations of chimps using tools, Leakey wrote, “Now we must redefine tool, redefine Man, or accept chimpanzees as human.”

Goodall spoke of animals as having emotions and cultures, and in the case of chimps, communities that were almost tribal. She also named the chimps she observed, an unheard-of practice at the time, garnering ridicule from scientists who had traditionally numbered their research subjects.

One of her most remarkable observations became known as the Gombe Chimp War. It was a four-year-long conflict in which eight adult males from one community killed all six males of another community, taking over their territory, only to lose it to another, bigger community with even more males.

Confidence in her path

Goodall was persuasive, powerful and determined, and she often advised me not to succumb to people’s criticisms. Her path to groundbreaking discoveries did not involve stepping on people or elbowing competitors aside.

Rather, her journey to Africa was motivated by her wonder, her love of animals and a powerful imagination. As a little girl, she was entranced by Edgar Rice Burroughs’ 1912 story “Tarzan of the Apes,” and she loved to joke that Tarzan married the wrong Jane.

When I was a 23-year-old former NFL cheerleader, with no scientific background at that time, and looked at Goodall’s work, I imagined that I, too, could be like her. In large part because of her, I became a primatologist, co-discovered a new species of lemur in Madagascar and have had an amazing life and career, in science and on TV, as a National Geographic explorer.

When it came time to write my own story, I asked Goodall to contribute the introduction. She wrote:

“Mireya Mayor reminds me a little of myself. Like me she loved being with animals when she was a child. And like me she followed her dream until it became a reality.”

In a 2023 interview, Jane Goodall answers TV host Jimmy Kimmel’s questions about chimpanzee behavior.

Storyteller and teacher

Goodall was an incredible storyteller and saw it as the most successful way to help people understand the true nature of animals. With compelling imagery, she shared extraordinary stories about the intelligence of animals, from apes and dolphins to rats and birds, and, of course, the octopus. She inspired me to become a wildlife correspondent for National Geographic so that I could share the stories and plights of endangered animals around the world.

Goodall inspired and advised world leaders, celebrities, scientists and conservationists. She also touched the lives of millions of children.

Through the Jane Goodall Institute, which works to engage people around the world in conservation, she launched Roots & Shoots, a global youth program that operates in more than 60 countries. The program teaches children about connections between people, animals and the environment, and ways to engage locally to help all three.

Along with Goodall’s warmth, friendship and wonderful stories, I treasure this comment from her: “The greatest danger to our future is our apathy. Each one of us must take responsibility for our own lives, and above all, show respect and love for living things around us, especially each other.”

It’s a radical notion from a one-of-a-kind scientist.

This article has been updated to add the date of Goodall’s death.

Mireya Mayor, Director of Exploration and Science Communication, Florida International University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

That comment by Jane that was treasured by Mireya is so important. “The greatest danger to our future is our apathy. Each one of us must take responsibility for our own lives, and above all, show respect and love for living things around us, especially each other.”