Protecting our right to breathe good, clean air.

Fundamentally, today’s post is not about dogs. But it is about the qualities that we can see in our dogs: trust, honesty, openness, and the core quality that inspires my writings about dogs: integrity.

I’m speaking of the disgusting news that has been headlined in the world’s media in recent days, no better summarised than by this extract from a current (1pm PDT yesterday)) BBC news report:

Volkswagen chief executive Martin Winterkorn has resigned following the revelation that the firm manipulated US diesel car emissions tests.

Mr Winterkorn said he was “shocked” by recent events and that the firm needed a “fresh start”.

He added that he was “not aware of any wrongdoing on my part” but was acting in the interest of the company.

VW has already said that it is setting aside €6.5bn (£4.7bn) to cover the costs of the scandal.

The world’s biggest carmaker admitted last week that it deceived US regulators in exhaust emissions tests by installing a device to give more positive results.

The company said later that it affected 11 million vehicles worldwide.

As ever, the voice of George Monbiot speaks a little clearer than most, and I am referring to his recent essay published both on his blog and in The Guardian newspaper. I am very pleased to have Monbiot’s permission to republish his essay here on Learning from Dogs.

ooOOoo

Smoke and Mirrors

22nd September 2015

Pollution, as scandals on both sides of the Atlantic show, is a physical manifestation of corruption.

By George Monbiot, published in the Guardian 23 September 2015

In London, the latest figures suggest, it now kills more people than smoking. Worldwide, a new study estimates, it causes more deaths than malaria and HIV-Aids together. I’m talking about the neglected health crisis of this age, that we seldom discuss or even acknowledge. Air pollution.

Heart attacks, strokes, asthma, lung and bladder cancers, low birth weight, low verbal IQ, poor memory and attention among children, faster cognitive decline in older people and – recent studies suggest – a link with the earlier onset of dementia: all these are among the impacts of a problem that, many still believe, we solved decades ago. The smokestacks may have moved to China, but other sources, whose fumes are less visible, have taken their place. Among the worst are diesel engines, sold, even today, as the eco-friendly option, on the grounds that their greenhouse gas emissions tend to be lower than those of petrol engines. You begin to wonder whether any such claims can still be trusted.

Volkswagen’s rigging of its pollution tests is an assault on our lungs, our hearts, our brains. It is a classic example of externalisation: the dumping of costs that businesses should carry onto other people. The air that should have been filtered by its engines is filtered by our lungs instead. We have become the scrubbing devices it failed to install.

Who knows how many people have paid for this crime already, with their health or with their lives? In the USA, 200,000 deaths a year are attributed to air pollution. For how many of those might Volkswagen be responsible? Where else was the fraud perpetrated? Of what proportion of our health budgets has this company robbed us?

The fraud involves the detection of nitrogen oxides (NOx), of which diesel engines are the major source in many places. This month, for the first time in our history, the UK government estimated the impact of NOx emissions on public health, and discovered that they are likely almost to double the number of deaths from air pollution, adding 23,000 to the 29,000 attributed to particulates (tiny particles of soot).

The government released this discovery, alongside its useless proposals for dealing with the problem, on Saturday 12 September, a few minutes before Jeremy Corbyn’s election as Labour leader was announced. How many government press releases are published on a Saturday? How many are published on a Saturday during an event on which everyone is focused? In other words, as a Labour press officer once notoriously advised, this was “a good day to bury bad news”. Not only was the number of deaths buried by this means, but so was the government’s consultation on its feeble plans for reducing this pollution: a consultation to which it evidently wanted as few respondents as possible. Liz Truss, the environment secretary, has some explaining to do.

She has her reasons for keeping us in the dark. In April, the Supreme Court ruled that the UK is in breach of the European air quality directive, and insisted that the government draw up a plan for compliance by the end of this year. Instead, Truss produced a plan to shed responsibility. Local authorities, her consultation suggests, should create clean air zones in at least eight cities, in which diesel engines are restricted or banned. But she has given them neither new money nor new powers. Nor has she offered an explanation of how this non-plan is going to address the issue in the rest of the country, as the ruling demands.

Already, the UK has missed the European deadline by six years. Under Truss’s proposals, some places are likely still to be in breach by 2025: 16 years after the original deadline. I urge you to respond to the consultation she wanted you to miss, which closes on November 6.

The only concrete plan the government has produced so far is to intensify the problem, through a new programme of airport expansion. This means more nitrous oxides, more particulates, more greenhouse gas emissions.

Paradoxically, the Volkswagen scandal may succeed where all else has failed, by obliging the government to take the only action that will make a difference: legislating for a great reduction in the use of diesel engines. By the time this article is published, we might know whether the company’s scam has been perpetrated in Europe as well as North America: new revelations are dripping by the hour. But whether or not this particular deception was deployed here, plenty of others have been.

Last week the Guardian reported that nine out of ten new diesel cars break European limits on nitrous oxides – not by a little but by an average of sevenfold. Every manufacturer whose emissions were tested had cars in breach of the legal limit. They used a number of tricks to hotwire the tests: “stripping components from the car to reduce weight, using special lubricants, over-inflating tyres and using super-smooth test tracks.” In other words, the emissions scandal is not confined to Volkswagen, not confined to a single algorithm and not confined to North America: it looks, in all its clever variants, like a compound global swindle.

There are echoes here of the ploys used by the tobacco industry: grand deceptions smuggled past the public with the help of sophisticated marketing. Volkswagen sites advertising the virtues of “clean diesel” have been dropping offline all day. In 2009, the year in which its scam began, the TDI engine at the centre of the scandal won the Volkswagen Jetta 2.0 the green car of the year award. In 2010, it did the same for the Audi A3.

There’s plenty that’s wrong with corporate regulation in the United States, but at least the fines, when they occur, are big enough to make a corporation pause, and there’s a possibility of guilty executives ending up in prison. Here, where corruption, like pollution, is both omnipresent and invisible, major corporations can commit almost any white-collar crime and get away with it. Schemes of the kind that have scandalised America are, in this country, both commonplace and unremarked. How can such governments be trusted to defend our health?

www.monbiot.com

ooOOoo

I found myself having two emotional reactions to Monbiot’s essay. The first was that for many years, when I was living and working in England, I drove diesel-powered cars on the (now false) belief that they were better for the environment.

My second reaction was to Monbiot listing the likely impacts from air pollution,”Heart attacks, strokes, asthma, lung and bladder cancers, low birth weight, low verbal IQ, poor memory and attention among children, faster cognitive decline in older people and – recent studies suggest – a link with the earlier onset of dementia. . . “, for the reason that at the age of 70, I am already noticing the creeping onset of reduced verbal IQ, cognitive decline, and worry about the onset of dementia. To think that my earlier decisions about what cars to drive might be a factor in this is disturbing.

I am going to close this post by highlighting how fighting for what we want is important, critically so. By republishing an item that was posted on AmericaBlog just over a year ago, that fortuitously is a reward for living in the State of Oregon.

ooOOoo

Climate win: Appeals court in Oregon rules state court must decide if atmosphere is a “public trust”

6/16/14 10:00am by Gaius Publius

Two teenagers from Eugene, Ore. filed suit against Governor Kitzhaber and the State of Oregon for failing to protect the “atmosphere, state waters, and coast lines, as required under the public trust doctrine.”

They lost the first round, where the state court said that climate relief was not a judicial matter. But they won on appeal. The case goes back to the original court, which now has orders to decide the case on its merits and not defer to the executive or legislature.

The gist of the appeals court decision:

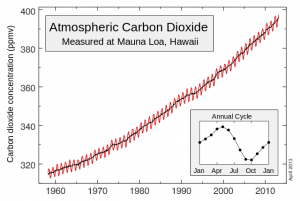

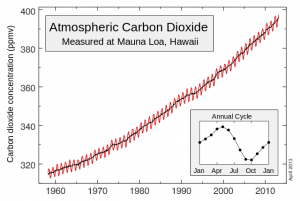

Their lawsuit asked the State to take action in restoring the atmosphere to 350 ppm of CO2 by the end of the century. The Oregon Court of Appeals rejected the defenses raised by the State, finding that the youth could obtain meaningful judicial relief in this case.

That’s quite a nice victory. Here’s the full story, from the Western Environmental Law Center (my emphasis throughout):

In a nationally significant decision in the case Chernaik v. Kitzhaber, the Oregon Court of Appeals ruled a trial court must decide whether the atmosphere is a public trust resource that the state of Oregon, as a trustee, has a duty to protect. Two youth plaintiffs were initially told they could not bring the case by the Lane County Circuit Court. The trial court had ruled that climate change should be left only to the legislative and executive branches. Today, the Oregon Court of Appeals overturned that decision.

Two teenagers from Eugene, Kelsey Juliana and Olivia Chernaik, filed the climate change lawsuit against Governor Kitzhaber and the State of Oregon for failing to protect essential natural resources, including the atmosphere, state waters, and coast lines, as required under the public trust doctrine. Their lawsuit asked the State to take action in restoring the atmosphere to 350 ppm of CO2 by the end of the century. The Oregon Court of Appeals rejected the defenses raised by the State, finding that the youth could obtain meaningful judicial relief in this case. …

In reversing the Lane County trial court, the Oregon Court of Appeals remanded the case ordering the trial court to make the judicial declaration it previously refused to make as to whether the State, as trustee, has a fiduciary obligation to protect the youth from the impacts of climate change, and if so, what the State must do to protect the atmosphere and other public trust resources.

The implications of this are broad, and similar cases are pending in other states, as the article describes.

Make no mistake; decisions like this matter. It places the court squarely in the mix as a power player in the climate war, the fight for “intergenerational justice” as James Hansen puts it — or the war against intergenerational betrayal, as I put it.

This is a cornerstone decision from the Oregon Court of Appeals in climate change jurisprudence. The court definitively ruled that the question of whether government has an obligation to protect the atmosphere from degradation leading to climate change is a question for the judiciary, and not for the legislative or executive branches. The Court did not opine as to how that question should be answered, only that it should be answered by the judiciary.

We can win this; it’s not over. If we reach 450 ppm and we’re still not stopping with the CO2, then it’s over and I become a novelist full-time. But we’re not there yet, and please don’t surrender as if we were.

The courts are now a powerful tool, as is divestment. James Hansen has a way to restore the atmosphere to 350 ppm CO2 in time to stop slow feedbacks from kicking in. It’s a doable plan, but we’ll need to use force. Using the courts, as with using divestment campaigns, counts as force. Stay tuned.

(Want to use force at the national level? Find a way to challenge Obama publicly to stop leasing federal land to coal companies. He’s a hypocrite until he stops federal coal from being mined and sold abroad. A simple and obvious challenge for him. You too can be the activist.)

GP

Twitter: @Gaius_Publius

Facebook: Gaius Publi

(Facebook note: To get the most from a Facebook recommendation, be sure to Share what you also Like. Thanks.)

ooOOoo

Never forget that you, me and every other good-minded person on this planet can make a positive difference. Need inspiration? Gain it from our dogs! Let’s use the liberty we enjoy to make a difference.