What is happening in beautiful Indonesia is beyond imagination.

I am indebted to John Zande for introducing me to the word kakistocracy, that he explained means: “government by the worst persons; a form of government in which the worst persons are in power.”

For what is happening in Indonesia could well be an awful example of kakistocracy in action.

Like numerous others I knew that there were fires burning in Indonesia and that it was all somehow caught up in illegal logging, but knew little over and above that. And that is the crux of the title of a recent essay from George Monbiot: Nothing to See Here. It really is a “must read” essay and is republished below with Mr. Monbiot’s very kind permission. As with most of his essays, they are published in the Guardian newspaper. In this case, the Guardian version includes photographs that vividly underline the terrible situation out there. I agonised about copying them from the Guardian article, without explicit permission to so do, but have nevertheless done so on the basis of this story needing to make the maximum impact on readers. The photographs are inserted in Monbiot’s essay very closely to the format that is presented in the Guardian article.

ooOOoo

Nothing to See Here

30th October 2015

In the greatest environmental disaster of the 21st Century (so far), Indonesia has been blotted out by smoke. And the media.

By George Monbiot, published in the Guardian 30th October 2015.

I’ve often wondered how the media would respond when eco-apocalypse struck. I pictured the news programmes producing brief, sensational reports, while failing to explain why it was happening or how it might be stopped. Then they would ask their financial correspondents how the disaster affected share prices, before turning to the sport. As you can probably tell, I don’t have an ocean of faith in the industry for which I work.

What I did not expect was that they would ignore it.

A great tract of the Earth is on fire. It looks as you might imagine hell to be. The air has turned ochre: visibility in some cities has been reduced to 30 metres. Children are being prepared for evacuation in warships; already some have choked to death. Species are going up in smoke at an untold rate. It is almost certainly the greatest environmental disaster of the 21st Century – so far.

[NB: The video that is embedded in the Guardian version is without sound. I have added one that is also a Greenpeace video, with sound, further on in the post.]

And the media? It’s talking about the dress the Duchess of Cambridge wore to the James Bond premiere, Donald Trump’s idiocy du jour and who got eliminated from the Halloween episode of Dancing with the Stars. The great debate of the week, dominating the news across much of the world? Sausages: are they really so bad for your health?

What I’m discussing is a barbeque on a different scale. Fire is raging across the 5000-kilometre length of Indonesia. It is surely, on any objective assessment, more important than anything else taking place today. And it shouldn’t require a columnist, writing in the middle of a newspaper, to say so. It should be on everyone’s front page.

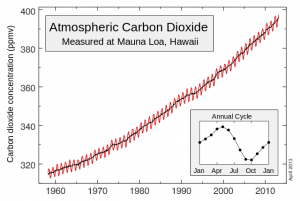

It is hard to convey the scale of this inferno, but here’s a comparison that might help: it is currently producing more carbon dioxide than the US economy. In three weeks the fires have released more CO2 than the annual emissions of Germany.

But that doesn’t really capture it. This catastrophe cannot be measured only in parts per million. The fires are destroying treasures as precious and irreplaceable as the archaeological remains being levelled by Isis. Orang utans, clouded leopards, sun bears, gibbons, the Sumatran rhinoceros and Sumatran tiger, these are among the threatened species being driven from much of their range by the flames. But there are thousands, perhaps millions, more.

One of the burning islands is West Papua, a nation that has been illegally occupied by Indonesia since 1963. I spent six months there when I was 24, investigating some of the factors that have led to the current disaster. At the time, it was a wonderland, rich with endemic species in every swamp and valley. Who knows how many of those have vanished in the past few weeks? This week I have pored and wept over photos of places I loved, that have now been reduced to ash.

Nor do the greenhouse gas emissions capture the impact on the people of these lands. After the last great conflagration, in 1997, there was a missing cohort in Indonesia of 15,000 children under the age of three, attributed to air pollution. This, it seems, is worse. The surgical masks being distributed across the nation will do almost nothing to protect those living in a sunless smog. Members of parliament in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) have had to wear face masks during debates. The chamber is so foggy that they must have difficulty recognising each other.

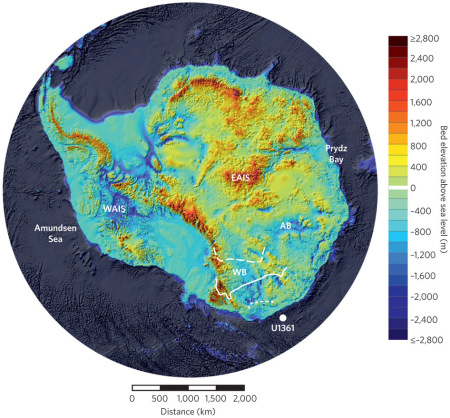

It’s not just the trees that are burning. It is the land itself. Much of the forest sits on great domes of peat. When the fires penetrate the earth, they smoulder for weeks, sometimes months, releasing clouds of methane, carbon monoxide, ozone and exotic gases like ammonium cyanide. The plumes extend for hundreds of miles, causing diplomatic conflicts with neighbouring countries.

Why is this happening? Indonesia’s forests have been fragmented for decades by timber and farming companies. Canals have been cut through the peat to drain and dry it. Plantation companies move in to destroy what remains of the forest to plant monocultures of pulpwood, timber and palm oil. The easiest way to clear the land is to torch it. Every year, this causes disasters. But in an extreme El Niño year like this one, we have a perfect formula for environmental catastrophe.

The current president, Joko Widodo, is – or wants to be – a democrat. But he presides over a nation in which fascism and corruption flourish. As Joshua Oppenheimer’s documentary The Act of Killing shows, leaders of the death squads that helped murder around a million people during Suharto’s terror in the 1960s, with the approval of the West, have since prospered through other forms of organised crime, including illegal deforestation.

They are supported by a paramilitary organisation with three million members, called Pancasila Youth. With its orange camo-print uniforms, scarlet berets, sentimental gatherings and schmaltzy music, it looks like a fascist militia as imagined by JG Ballard. There has been no truth, no reconciliation; the mass killers are still greeted as heroes and feted on television. In some places, especially West Papua, the political murders continue.

Those who commit crimes against humanity don’t hesitate to commit crimes against nature. Though Joko Widodo seems to want to stop the burning, his reach is limited. His government’s policies are contradictory: among them are new subsidies for palm oil production that make further burning almost inevitable. Some plantation companies, prompted by their customers, have promised to stop destroying the rainforest. Government officials have responded angrily, arguing that such restraint impedes the country’s development. That smoke blotting out the nation, which has already cost it some $30 billion? That, apparently, is development.

Our leverage is weak, but there are some things we can do. Some companies using palm oil have made visible efforts to reform their supply chains; but others seem to move slowly and opaquely. Starbucks, PepsiCo, Kraft Heinz and Unilever are examples. Don’t buy their products until they change.

On Monday, Widodo was in Washington, meeting Barack Obama. Obama, the official communiqué recorded, “welcomed President Widodo’s recent policy actions to combat and prevent forest fires”. The ecopalypse taking place as they conferred, that makes a mockery of these commitments, wasn’t mentioned.

Governments ignore issues when the media ignores them. And the media ignores them because … well there’s a question with a thousand answers, many of which involve power. But one reason is the complete failure of perspective in a deskilled industry dominated by corporate press releases, photo ops and fashion shoots, where everyone seems to be waiting for everyone else to take a lead. The media makes a collective non-decision to treat this catastrophe as a non-issue, and we all carry on as if it’s not happening.

At the climate summit in Paris in December, the media, trapped within the intergovernmental bubble of abstract diplomacy and manufactured drama, will cover the negotiations almost without reference to what is happening elsewhere. The talks will be removed to a realm with which we have no moral contact. And, when the circus moves on, the silence will resume. Is there any other industry that serves its customers so badly?

ooOOoo

Here is that Greenpeace video I referred to above.

Published on Oct 30, 2015

URGENT: Forest fires are raging through Indonesia, putting endangered orangutans and human health at risk.Join the call to stop the fires and prevent them from ever happening again – http://www.greenpeace.org.uk/forestfires

A quick web search will offer endless pictures of this great tragedy but I will leave you with three; two showing the extent of the smoke and one that is much more an intimate photograph of the suffering animals.

oooo

oooo

Binsar Bakkara, Associated Press.

Monbiot wrote: “Those who commit crimes against humanity don’t hesitate to commit crimes against nature.”

One cannot avoid reflecting that this would not have happened if there hadn’t been, “government by the worst persons; a form of government in which the worst persons are in power.”

Welcome to kakistocracy.