Where is the global climate going?

The challenge with writing posts, albeit not so often, about the global environment, especially when I am a non-scientist, is that one relies entirely on the words of others. In the case of a recent article, published by The Conversation, the authors are claimed to be specialists, and I do not doubt their credentials.

The three authors are René van Westen who is a Postdoctoral Researcher in Climate Physics, at Utrecht University, Henk A. Dijkstra who is a Professor of Physics, also at Utrecht University, and Michael Kliphuis, a Climate Model Specialist, again at Utrecht University.

So, here is their article:

ooOOoo

Atlantic Ocean is headed for a tipping point − once melting glaciers shut down the Gulf Stream, we would see extreme climate change within decades, study shows

René van Westen, Utrecht University; Henk A. Dijkstra, Utrecht University, and Michael Kliphuis, Utrecht University

Superstorms, abrupt climate shifts and New York City frozen in ice. That’s how the blockbuster Hollywood movie “The Day After Tomorrow” depicted an abrupt shutdown of the Atlantic Ocean’s circulation and the catastrophic consequences.

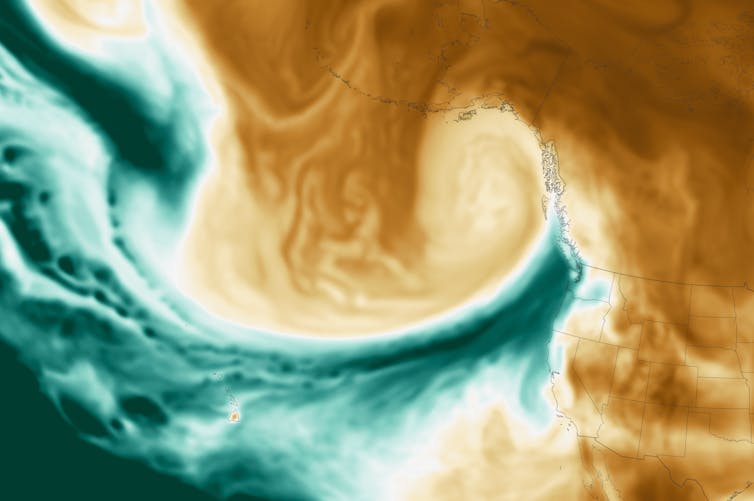

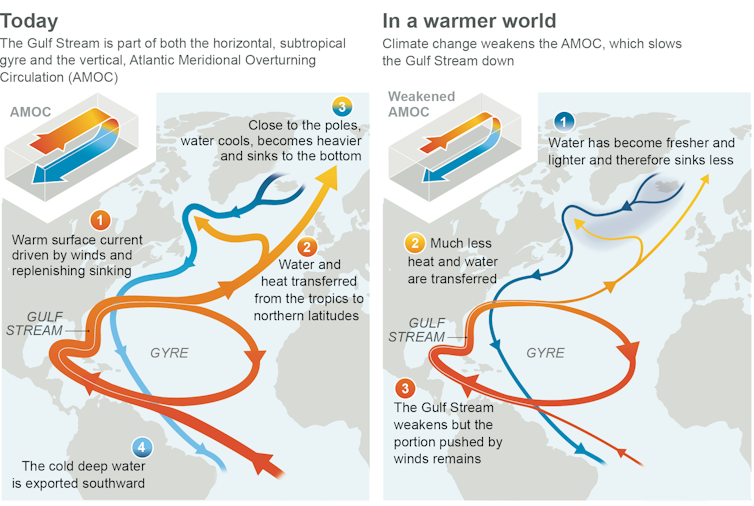

While Hollywood’s vision was over the top, the 2004 movie raised a serious question: If global warming shuts down the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, which is crucial for carrying heat from the tropics to the northern latitudes, how abrupt and severe would the climate changes be?

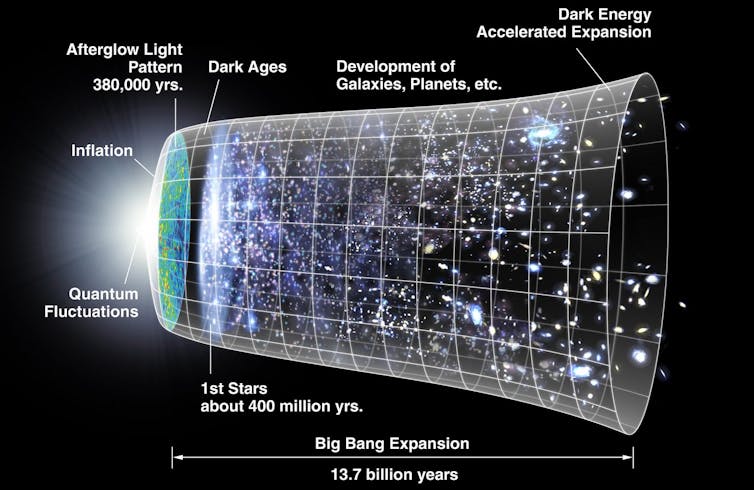

Twenty years after the movie’s release, we know a lot more about the Atlantic Ocean’s circulation. Instruments deployed in the ocean starting in 2004 show that the Atlantic Ocean circulation has observably slowed over the past two decades, possibly to its weakest state in almost a millennium. Studies also suggest that the circulation has reached a dangerous tipping point in the past that sent it into a precipitous, unstoppable decline, and that it could hit that tipping point again as the planet warms and glaciers and ice sheets melt.

In a new study using the latest generation of Earth’s climate models, we simulated the flow of fresh water until the ocean circulation reached that tipping point.

The results showed that the circulation could fully shut down within a century of hitting the tipping point, and that it’s headed in that direction. If that happened, average temperatures would drop by several degrees in North America, parts of Asia and Europe, and people would see severe and cascading consequences around the world.

We also discovered a physics-based early warning signal that can alert the world when the Atlantic Ocean circulation is nearing its tipping point.

The ocean’s conveyor belt

Ocean currents are driven by winds, tides and water density differences.

In the Atlantic Ocean circulation, the relatively warm and salty surface water near the equator flows toward Greenland. During its journey it crosses the Caribbean Sea, loops up into the Gulf of Mexico, and then flows along the U.S. East Coast before crossing the Atlantic.

This current, also known as the Gulf Stream, brings heat to Europe. As it flows northward and cools, the water mass becomes heavier. By the time it reaches Greenland, it starts to sink and flow southward. The sinking of water near Greenland pulls water from elsewhere in the Atlantic Ocean and the cycle repeats, like a conveyor belt.

Too much fresh water from melting glaciers and the Greenland ice sheet can dilute the saltiness of the water, preventing it from sinking, and weaken this ocean conveyor belt. A weaker conveyor belt transports less heat northward and also enables less heavy water to reach Greenland, which further weakens the conveyor belt’s strength. Once it reaches the tipping point, it shuts down quickly.

What happens to the climate at the tipping point?

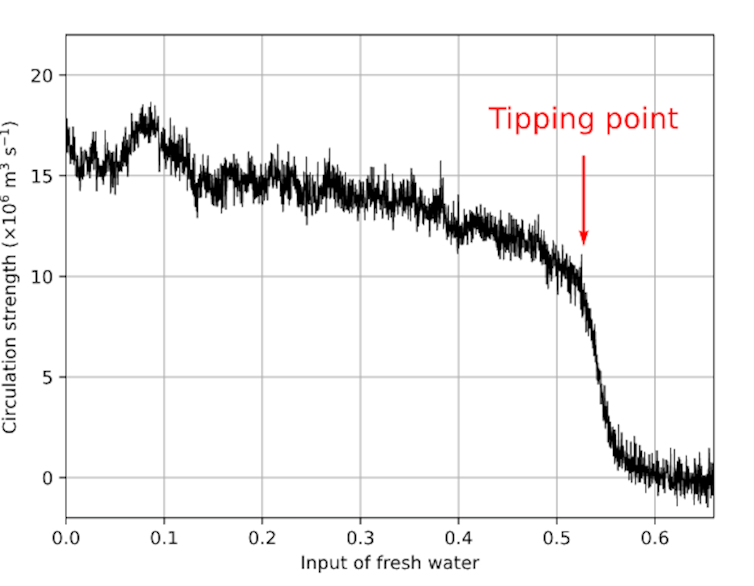

The existence of a tipping point was first noticed in an overly simplified model of the Atlantic Ocean circulation in the early 1960s. Today’s more detailed climate models indicate a continued slowing of the conveyor belt’s strength under climate change. However, an abrupt shutdown of the Atlantic Ocean circulation appeared to be absent in these climate models. https://www.youtube.com/embed/p4pWafuvdrY?wmode=transparent&start=0 How the ocean conveyor belt works.

This is where our study comes in. We performed an experiment with a detailed climate model to find the tipping point for an abrupt shutdown by slowly increasing the input of fresh water.

We found that once it reaches the tipping point, the conveyor belt shuts down within 100 years. The heat transport toward the north is strongly reduced, leading to abrupt climate shifts.

The result: Dangerous cold in the North

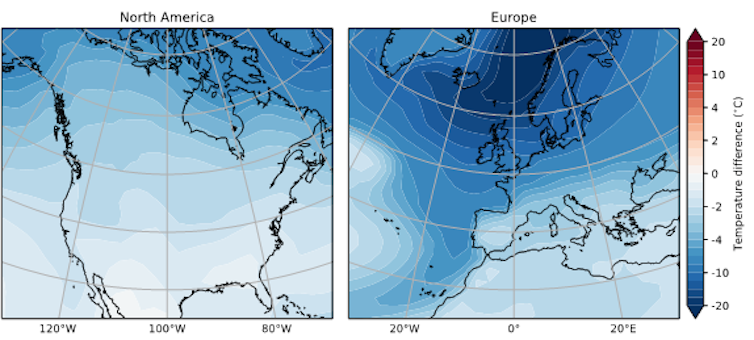

Regions that are influenced by the Gulf Stream receive substantially less heat when the circulation stops. This cools the North American and European continents by a few degrees.

The European climate is much more influenced by the Gulf Stream than other regions. In our experiment, that meant parts of the continent changed at more than 5 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius) per decade – far faster than today’s global warming of about 0.36 F (0.2 C) per decade. We found that parts of Norway would experience temperature drops of more than 36 F (20 C). On the other hand, regions in the Southern Hemisphere would warm by a few degrees.

These temperature changes develop over about 100 years. That might seem like a long time, but on typical climate time scales, it is abrupt.

The conveyor belt shutting down would also affect sea level and precipitation patterns, which can push other ecosystems closer to their tipping points. For example, the Amazon rainforest is vulnerable to declining precipitation. If its forest ecosystem turned to grassland, the transition would release carbon to the atmosphere and result in the loss of a valuable carbon sink, further accelerating climate change.

The Atlantic circulation has slowed significantly in the distant past. During glacial periods when ice sheets that covered large parts of the planet were melting, the influx of fresh water slowed the Atlantic circulation, triggering huge climate fluctuations.

So, when will we see this tipping point?

The big question – when will the Atlantic circulation reach a tipping point – remains unanswered. Observations don’t go back far enough to provide a clear result. While a recent study suggested that the conveyor belt is rapidly approaching its tipping point, possibly within a few years, these statistical analyses made several assumptions that give rise to uncertainty.

Instead, we were able to develop a physics-based and observable early warning signal involving the salinity transport at the southern boundary of the Atlantic Ocean. Once a threshold is reached, the tipping point is likely to follow in one to four decades.

The climate impacts from our study underline the severity of such an abrupt conveyor belt collapse. The temperature, sea level and precipitation changes will severely affect society, and the climate shifts are unstoppable on human time scales.

It might seem counterintuitive to worry about extreme cold as the planet warms, but if the main Atlantic Ocean circulation shuts down from too much meltwater pouring in, that’s the risk ahead.

This article was updated to Feb. 11, 2024, to fix a typo: The experiment found temperatures in parts of Europe changed by more than 5 F per decade.

René van Westen, Postdoctoral Researcher in Climate Physics, Utrecht University; Henk A. Dijkstra, Professor of Physics, Utrecht University, and Michael Kliphuis, Climate Model Specialist, Utrecht University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

I am 79! I like to think that whatever is coming down the wires, so to speak, will be after my death. But that is a cop out for a) I have a son and a daughter who are in their early fifties, b) I have a grandson, my daughter and son-in-law’s young man, who is a teenager, with his birthday next month, and c) I could possibly live for another twenty years.

The challenge is how to bring this imminent catastrophic global change in temperature to the fore. We need a global solution now enforced by a globally respected group of scientists and leaders, and, frankly, I do not see that happening.

All one can do is to hope. Hope that the global community will eschew the present-day extremes of warring behaviour and see the need for change. That is NOW!

So that the Hollywood movie, The Day After Tomorrow, remains a fictional story. And for those that have forgotten the film or who have never seen it, here is a small slice of a Wikipedia report:

The Day After Tomorrow is a 2004 American science fiction disaster film conceived, co-written, directed, co-produced by Roland Emmerich, based on the 1999 book The Coming Global Superstorm by Art Bell and Whitley Strieber, and starring Dennis Quaid, Jake Gyllenhaal, Sela Ward, Emmy Rossum, and Ian Holm. The film depicts catastrophic climatic effects following the disruption of the North Atlantic Ocean circulation, in which a series of extreme weather events usher in climate change and lead to a new ice age.

Wikipedia

And here is a YouTube video:

There we go, folks!