Amazing what science can find out.

But while the science is brilliant the social implications are not so good. Read on!

ooOOoo

A billion-dollar drug was found in Easter Island soil – what scientists and companies owe the Indigenous people they studied

Ted Powers, University of California, Davis

An antibiotic discovered on Easter Island in 1964 sparked a billion-dollar pharmaceutical success story. Yet the history told about this “miracle drug” has completely left out the people and politics that made its discovery possible.

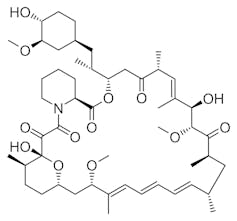

Named after the island’s Indigenous name, Rapa Nui, the drug rapamycin was initially developed as an immunosuppressant to prevent organ transplant rejection and to improve the efficacy of stents to treat coronary artery disease. Its use has since expanded to treat various types of cancer, and researchers are currently exploring its potential to treat diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases and even aging. Indeed, studies raising rapamycin’s promise to extend lifespan or combat age-related diseases seem to be published almost daily. A PubMed search reveals over 59,000 journal articles that mention rapamycin, making it one of the most talked-about drugs in medicine.

At the heart of rapamycin’s power lies its ability to inhibit a protein called the target of rapamycin kinase, or TOR. This protein acts as a master regulator of cell growth and metabolism. Together with other partner proteins, TOR controls how cells respond to nutrients, stress and environmental signals, thereby influencing major processes such as protein synthesis and immune function. Given its central role in these fundamental cellular activities, it is not surprising that cancer, metabolic disorders and age-related diseases are linked to the malfunction of TOR.

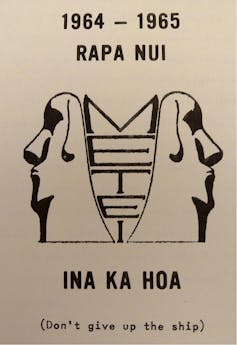

Despite being so ubiquitous in science and medicine, how rapamycin was discovered has remained largely unknown to the public. Many in the field are aware that scientists from the pharmaceutical company Ayerst Research Laboratories isolated the molecule from a soil sample containing the bacterium Streptomyces hydroscopicus in the mid-1970s. What is less well known is that this soil sample was collected as part of a Canadian-led mission to Rapa Nui in 1964, called the Medical Expedition to Easter Island, or METEI.

As a scientist who built my career around the effects of rapamycin on cells, I felt compelled to understand and share the human story underlying its origin. Learning about historian Jacalyn Duffin’s work on METEI completely changed how I and many of my colleagues view our own field.

Unearthing rapamycin’s complex legacy raises important questions about systemic bias in biomedical research and what pharmaceutical companies owe to the Indigenous lands from which they mine their blockbuster discoveries.

History of METEI

The Medical Expedition to Easter Island was the brainchild of a Canadian team comprised of surgeon Stanley Skoryna and bacteriologist Georges Nogrady. Their goal was to study how an isolated population adapted to environmental stress, and they believed the planned construction of an international airport on Easter Island offered a unique opportunity. They presumed that the airport would result in increased outside contact with the island’s population, resulting in changes in their health and wellness.

With funding from the World Health Organization and logistical support from the Royal Canadian Navy, METEI arrived in Rapa Nui in December 1964. Over the course of three months, the team conducted medical examinations on nearly all 1,000 island inhabitants, collecting biological samples and systematically surveying the island’s flora and fauna.

It was as part of these efforts that Nogrady gathered over 200 soil samples, one of which ended up containing the rapamycin-producing Streptomyces strain of bacteria.

It’s important to realize that the expedition’s primary objective was to study the Rapa Nui people as a sort of living laboratory. They encouraged participation through bribery by offering gifts, food and supplies, and through coercion by enlisting a long-serving Franciscan priest on the island to aid in recruitment. While the researchers’ intentions may have been honorable, it is nevertheless an example of scientific colonialism, where a team of white investigators choose to study a group of predominantly nonwhite subjects without their input, resulting in a power imbalance.

There was an inherent bias in the inception of METEI. For one, the researchers assumed the Rapa Nui had been relatively isolated from the rest of the world when there was in fact a long history of interactions with countries outside the island, beginning with reports from the early 1700s through the late 1800s.

METEI also assumed that the Rapa Nui were genetically homogeneous, ignoring the island’s complex history of migration, slavery and disease. For example, the modern population of Rapa Nui are mixed race, from both Polynesian and South American ancestors. The population also included survivors of the African slave trade who were returned to the island and brought with them diseases, including smallpox.

This miscalculation undermined one of METEI’s key research goals: to assess how genetics affect disease risk. While the team published a number of studies describing the different fauna associated with the Rapa Nui, their inability to develop a baseline is likely one reason why there was no follow-up study following the completion of the airport on Easter Island in 1967.

Giving credit where it is due

Omissions in the origin stories of rapamycin reflect common ethical blind spots in how scientific discoveries are remembered.

Georges Nogrady carried soil samples back from Rapa Nui, one of which eventually reached Ayerst Research Laboratories. There, Surendra Sehgal and his team isolated what was named rapamycin, ultimately bringing it to market in the late 1990s as the immunosuppressant Rapamune. While Sehgal’s persistence was key in keeping the project alive through corporate upheavals – going as far as to stash a culture at home – neither Nogrady nor the METEI was ever credited in his landmark publications.

Although rapamycin has generated billions of dollars in revenue, the Rapa Nui people have received no financial benefit to date. This raises questions about Indigenous rights and biopiracy, which is the commercialization of Indigenous knowledge.

Agreements like the United Nations’s 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity and the 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples aim to protect Indigenous claims to biological resources by encouraging countries to obtain consent and input from Indigenous people and provide redress for potential harms before starting projects. However, these principles were not in place during METEI’s time.

Some argue that because the bacteria that produces rapamycin has since been found in other locations, Easter Island’s soil was not uniquely essential to the drug’s discovery. Moreover, because the islanders did not use rapamycin or even know about its presence on the island, some have countered that it is not a resource that can be “stolen.”

However, the discovery of rapamycin on Rapa Nui set the foundation for all subsequent research and commercialization around the molecule, and this only happened because the people were the subjects of study. Formally recognizing and educating the public about the essential role the Rapa Nui played in the eventual discovery of rapamycin is key to compensating them for their contributions.

In recent years, the broader pharmaceutical industry has begun to recognize the importance of fair compensation for Indigenous contributions. Some companies have pledged to reinvest in communities where valuable natural products are sourced. However, for the Rapa Nui, pharmaceutical companies that have directly profited from rapamycin have not yet made such an acknowledgment.

Ultimately, METEI is a story of both scientific triumph and social ambiguities. While the discovery of rapamycin has transformed medicine, the expedition’s impact on the Rapa Nui people is more complicated. I believe issues of biomedical consent, scientific colonialism and overlooked contributions highlight the need for a more critical examination and awareness of the legacy of breakthrough scientific discoveries.

Ted Powers, Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of California, Davis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

Ted Powers explains in the last paragraph: “Ultimately, METEI is a story of both scientific triumph and social ambiguities.” Then goes on to say: “I believe issues of biomedical consent, scientific colonialism and overlooked contributions highlight the need for a more critical examination and awareness of the legacy of breakthrough scientific discoveries.”

If only it was simple!