This attracted me very much, and I wanted to share it with you.

The opening paragraph of this article caught my eye so I read it fully. As it was published in The Conversation then that meant I could republish it.

ooOOoo

Centuries ago, the Maya storm god Huracán taught that when we damage nature, we damage ourselves

James L. Fitzsimmons, Middlebury

The ancient Maya believed that everything in the universe, from the natural world to everyday experiences, was part of a single, powerful spiritual force. They were not polytheists who worshipped distinct gods but pantheists who believed that various gods were just manifestations of that force.

Some of the best evidence for this comes from the behavior of two of the most powerful beings of the Maya world: The first is a creator god whose name is still spoken by millions of people every fall – Huracán, or “Hurricane.” The second is a god of lightning, K’awiil, from the early first millennium C.E.

As a scholar of the Indigenous religions of the Americas, I recognize that these beings, though separated by over 1,000 years, are related and can teach us something about our relationship to the natural world.

Huracán, the ‘Heart of Sky’

Huracán was once a god of the K’iche’, one of the Maya peoples who today live in the southern highlands of Guatemala. He was one of the main characters of the Popol Vuh, a religious text from the 16th century. His name probably originated in the Caribbean, where other cultures used it to describe the destructive power of storms.

The K’iche’ associated Huracán, which means “one leg” in the K’iche’ language, with weather. He was also their primary god of creation and was responsible for all life on earth, including humans.

Because of this, he was sometimes known as U K’ux K’aj, or “Heart of Sky.” In the K’iche’ language, k’ux was not only the heart but also the spark of life, the source of all thought and imagination.

Yet, Huracán was not perfect. He made mistakes and occasionally destroyed his creations. He was also a jealous god who damaged humans so they would not be his equal. In one such episode, he is believed to have clouded their vision, thus preventing them from being able to see the universe as he saw it.

Huracán was one being who existed as three distinct persons: Thunderbolt Huracán, Youngest Thunderbolt and Sudden Thunderbolt. Each of them embodied different types of lightning, ranging from enormous bolts to small or sudden flashes of light.

Despite the fact that he was a god of lightning, there were no strict boundaries between his powers and the powers of other gods. Any of them might wield lightning, or create humanity, or destroy the Earth.

Another storm god

The Popol Vuh implies that gods could mix and match their powers at will, but other religious texts are more explicit. One thousand years before the Popol Vuh was written, there was a different version of Huracán called K’awiil. During the first millennium, people from southern Mexico to western Honduras venerated him as a god of agriculture, lightning and royalty.

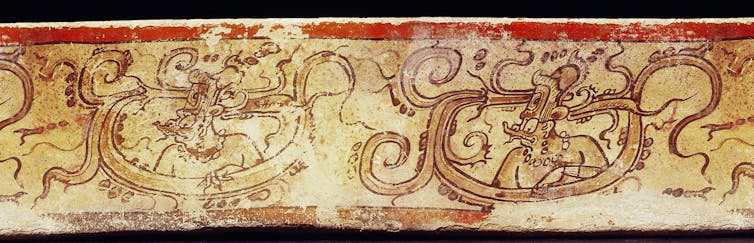

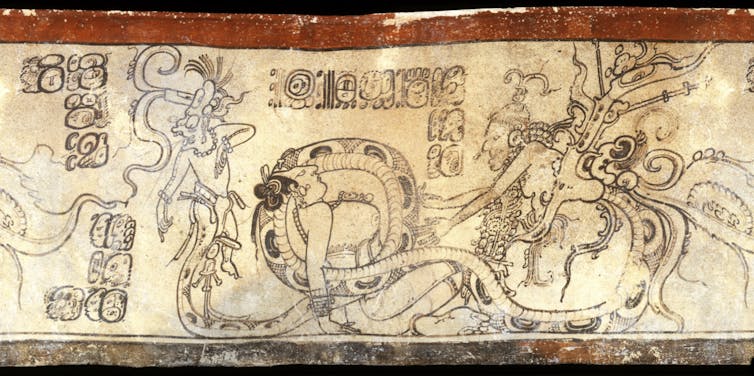

Illustrations of K’awiil can be found everywhere on Maya pottery and sculpture. He is almost human in many depictions: He has two arms, two legs and a head. But his forehead is the spark of life – and so it usually has something that produces sparks sticking out of it, such as a flint ax or a flaming torch. And one of his legs does not end in a foot. In its place is a snake with an open mouth, from which another being often emerges.

Indeed, rulers, and even gods, once performed ceremonies to K’awiil in order to try and summon other supernatural beings. As personified lightning, he was believed to create portals to other worlds, through which ancestors and gods might travel.

Representation of power

For the ancient Maya, lightning was raw power. It was basic to all creation and destruction. Because of this, the ancient Maya carved and painted many images of K’awiil. Scribes wrote about him as a kind of energy – as a god with “many faces,” or even as part of a triad similar to Huracán.

He was everywhere in ancient Maya art. But he was also never the focus. As raw power, he was used by others to achieve their ends.

Rain gods, for example, wielded him like an ax, creating sparks in seeds for agriculture. Conjurers summoned him, but mostly because they believed he could help them communicate with other creatures from other worlds. Rulers even carried scepters fashioned in his image during dances and processions.

Moreover, Maya artists always had K’awiil doing something or being used to make something happen. They believed that power was something you did, not something you had. Like a bolt of lightning, power was always shifting, always in motion.

An interdependent world

Because of this, the ancient Maya thought that reality was not static but ever-changing. There were no strict boundaries between space and time, the forces of nature or the animate and inanimate worlds.

Everything was malleable and interdependent. Theoretically, anything could become anything else – and everything was potentially a living being. Rulers could ritually turn themselves into gods. Sculptures could be hacked to death. Even natural features such as mountains were believed to be alive.

These ideas – common in pantheist societies – persist today in some communities in the Americas.

They were once mainstream, however, and were a part of K’iche’ religion 1,000 years later, in the time of Huracán. One of the lessons of the Popol Vuh, told during the episode where Huracán clouds human vision, is that the human perception of reality is an illusion.

The illusion is not that different things exist. Rather it is that they exist independent from one another. Huracán, in this sense, damaged himself by damaging his creations.

Hurricane season every year should remind us that human beings are not independent from nature but part of it. And like Hurácan, when we damage nature, we damage ourselves.

James L. Fitzsimmons, Professor of Anthropology, Middlebury

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

It is such a powerful message, that when we damage nature, we damage ourselves.

But I am unaware, no we are both unaware of a solution, and there doesn’t appear to be a government desire to make this the number one topic.

Please, if there is anyone who reads this post and has a more positive message then we would be very keen to hear from you.