Yesterday afternoon, around 4pm, local thunderstorm activity produced some rain. Not much but sufficient to wet the ground. It brought to an end several weeks of intense drought complicated by what is now more than 55,000 acres of fires burning in southwest Oregon: more details here.

Anyway, this is not about fire, irrespective of how potentially dangerous it can be in this part of the world, it is about water. So with that in mind, here’s a recent ‘Tomgram‘ from William deBuys, with introduction by Tom Engelhardt; republished with Tom’s generous permission.

Never Again Enough

Field Notes from a Drying West

By William deBuys

Several miles from Phantom Ranch, Grand Canyon, Arizona, April 2013 — Down here, at the bottom of the continent’s most spectacular canyon, the Colorado River growls past our sandy beach in a wet monotone. Our group of 24 is one week into a 225-mile, 18-day voyage on inflatable rafts from Lees Ferry to Diamond Creek. We settle in for the night. Above us, the canyon walls part like a pair of maloccluded jaws, and moonlight streams between them, bright enough to read by.

One remarkable feature of the modern Colorado, the great whitewater rollercoaster that carved the Grand Canyon, is that it is a tidal river. Before heading for our sleeping bags, we need to retie our six boats to allow for the ebb.

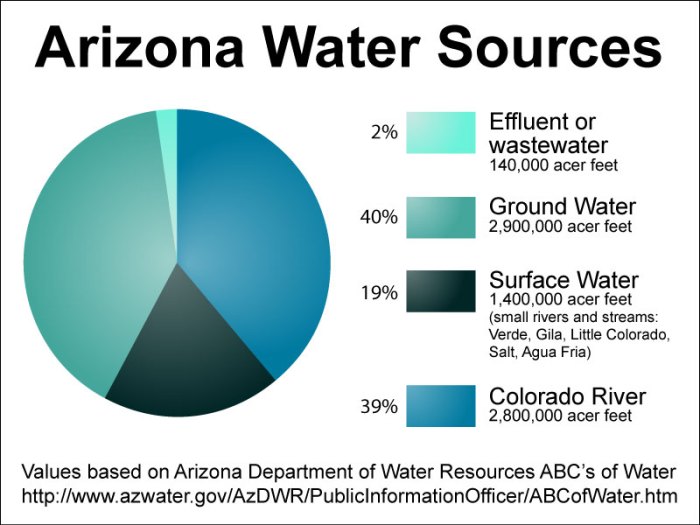

These days, the tides of the Colorado are not lunar but Phoenician. Yes, I’m talking about Phoenix, Arizona. On this April night, when the air conditioners in America’s least sustainable city merely hum, Glen Canyon Dam, immediately upstream from the canyon, will run about 6,500 cubic feet of water through its turbines every second.

Tomorrow, as the sun begins its daily broiling of Phoenix, Scottsdale, Mesa, Tempe, and the rest of central Arizona, the engineers at Glen Canyon will crank the dam’s maw wider until it sucks down 11,000 cubic feet per second (cfs). That boost in flow will enable its hydroelectric generators to deliver “peaking power” to several million air conditioners and cooling plants in Phoenix’s Valley of the Sun. And the flow of the river will therefore nearly double.

It takes time for these dam-controlled tidal pulses to travel downstream. Where we are now, just above Zoroaster Rapid, the river is roughly in phase with the dam: low at night, high in the daytime. Head a few days down the river and it will be the reverse.

By mid-summer, temperatures in Phoenix will routinely soar above 110°F, and power demands will rise to monstrous heights, day and night. The dam will respond: 10,000 cfs will gush through the generators by the light of the moon, 18,000 while an implacable sun rules the sky.

Such are the cycles — driven by heat, comfort, and human necessity — of the river at the bottom of the continent’s grandest canyon.

The crucial question for Phoenix, for the Colorado, and for the greater part of the American West is this: How long will the water hold out?

Major Powell’s Main Point

Every trip down the river — and there are more than 1,000 like ours yearly — partly reenacts the legendary descent of the Colorado by the one-armed explorer and Civil War veteran John Wesley Powell. The Major, as he preferred to be known, plunged into the Great Unknown with 10 companions in 1869. They started out in four boats from Green River, Wyoming, but one of the men walked out early after nearly drowning in the stretch of whitewater that Powell named Disaster Falls, and three died in the desert after the expedition fractured in its final miles. That left Powell and six others to reach the Mormon settlements on the Virgin River in the vicinity of present-day Las Vegas, Nevada.

Powell’s exploits on the Colorado brought him fame and celebrity, which he parlayed into a career that turned out to be controversial and illustrious in equal measure. As geologist, geographer, and ethnologist, Powell became one of the nation’s most influential scientists. He also excelled as an institution-builder, bureaucrat, political in-fighter, and national scold.

Most famously, and in bold opposition to the boomers and boosters then cheerleading America’s westward migration, he warned that the defining characteristic of western lands was their aridity. Settlement of the West, he wrote, would have to respect the limits aridity imposed.

He was half right.

The subsequent story of the West can indeed be read as an unending duel between society’s thirst and the dryness of the land, but in downtown Phoenix, Las Vegas, or Los Angeles you’d hardly know it.

By the middle years of the twentieth century, western Americans had created a kind of miracle in the desert, successfully conjuring abundance from Powell’s aridity. Thanks to reservoirs large and small, and scores of dams including colossi like Hoover and Glen Canyon, as well as more than 1,000 miles of aqueducts and countless pumps, siphons, tunnels, and diversions, the West has by now been thoroughly re-rivered and re-engineered. It has been given the plumbing system of a giant water-delivery machine, and in the process, its liquid resources have been stretched far beyond anything the Major might have imagined.

Today the Colorado River, the most fully harnessed of the West’s great waterways, provides water to some 40 million people and irrigates nearly 5.5 million acres of farmland. It also touches 22 Indian reservations, seven National Wildlife Reservations, and at least 15 units of the National Park System, including the Grand Canyon.

These achievements come at a cost. The Colorado River no longer flows to the sea, and down here in the bowels of the canyon, its diminishment is everywhere in evidence. In many places, the riverbanks wear a tutu of tamarisk trees along their edge. They have been able to dress up, now that the river, constrained from major flooding, no longer rips their clothes off.

The daily hydroelectric tides gradually wash away the sandbars and beaches that natural floods used to build with the river’s silt and bed load (the sands and gravels that roll along its bottom). Nowadays, nearly all that cargo is trapped in Lake Powell, the enormous reservoir behind Glen Canyon Dam. The water the dam releases is clear and cold (drawn from the depths of the lake), which is just the thing for nonnative trout, but bad news for homegrown chubs and suckers, which evolved, quite literally, in the murk of ages past. Some of the canyon’s native fish species have been extirpated from the canyon; others cling to life by a thread, helped by the protection of the Endangered Species Act. In the last few days, we’ve seen more fisheries biologists along the river and its side-streams than we have tourists.

The Shrinking Cornucopia

In the arid lands of the American West, abundance has a troublesome way of leading back again to scarcity. If you have a lot of something, you find a way to use it up — at least, that’s the history of the “development” of the Colorado Basin.

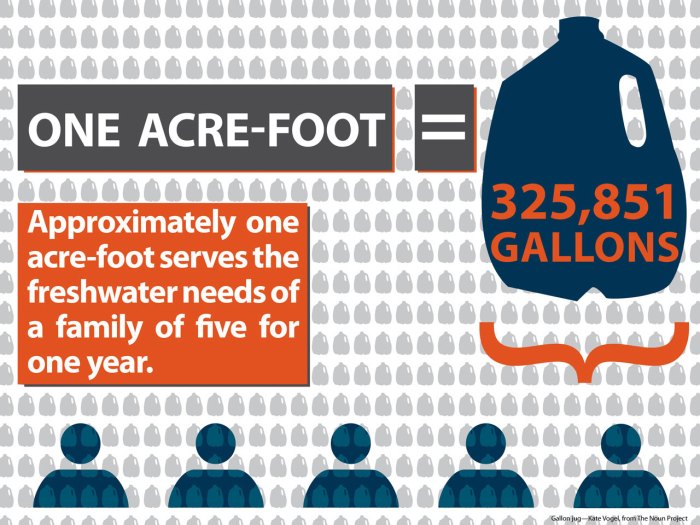

Until now, the ever-more-complex water delivery systems of that basin have managed to meet the escalating needs of their users. This is true in part because the states of the Upper Basin (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico) were slower to develop than their downstream cousins. Under theColorado River Compact of 1922, the Upper and Lower Basins divided the river with the Upper Basin assuring the Lower of an average of 7.5 million acre-feet (maf) of water per year delivered to Lees Ferry Arizona, the dividing point between the two. The Upper Basin would use the rest. Until recently, however, it left a large share of its water in the river, which California, and secondarily Arizona and Nevada, happily put to use.

Until now, the ever-more-complex water delivery systems of that basin have managed to meet the escalating needs of their users. This is true in part because the states of the Upper Basin (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico) were slower to develop than their downstream cousins. Under theColorado River Compact of 1922, the Upper and Lower Basins divided the river with the Upper Basin assuring the Lower of an average of 7.5 million acre-feet (maf) of water per year delivered to Lees Ferry Arizona, the dividing point between the two. The Upper Basin would use the rest. Until recently, however, it left a large share of its water in the river, which California, and secondarily Arizona and Nevada, happily put to use.

Those days are gone. The Lower Basin states now get only their annual entitlement and no more. Unfortunately for them, it’s not enough, and never will be.

Currently, the Lower Basin lives beyond its means — to the tune of about 1.3 maf per year, essentially consuming 117% of its allocation.

That 1.3 maf overage consists of evaporation, system losses, and the Lower Basin’s share of the annual U.S. obligation to Mexico of 1.5 maf. As it happens, the region budgets for none of these “costs” of doing business, and if pressed, some of its leaders will argue that the Mexican treaty is actually a federal responsibility, toward which the Lower Basin need not contribute water.

The Lower Basin funds its deficit by drawing on the accumulated water surplus held in the nation’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead, which backs up behind Hoover Dam. Unfortunately, with the Lower Basin using more water than it receives, the surplus there can’t last forever, and maybe not for long. In November 2010, the water level of the lake fell to its lowest elevation ever — 1,082 feet above sea level, a foot lower than its previous nadir during the fierce drought of the 1950s.

Had the dry weather held — and increasing doses of such weather are predicted for the region in the future — the reservoir would have soon fallen another seven feet and triggered the threshold for mandatory (but inadequate) cutbacks in water delivery to the Lower Basin states. Instead, heavy snowfall in the northern Rockies bailed out the system by producing a mighty runoff, lifting the reservoir a whopping 52 feet.

Since then, however, weather throughout the Colorado Basin has been relentlessly dry, and the lake has resumed its precipitous fall. It now stands at 1,106 feet, which translates to roughly 47% of capacity. Lake Powell, Mead’s alter ego, is in about the same condition.

Another dry year or two, and the Colorado system will be back where it was in 2010, staring down a crisis. There is, however, a consolation — of sorts. The Colorado is nowhere near as badly off as New Mexico and the Rio Grande.

How Dry I Am This Side of the Pecos

In May, New Mexico marked the close of the driest two-year period in the 120 years since records began to be kept. Its largest reservoir, Elephant Butte, which stores water from the Rio Grande, is effectively dry.

Meanwhile, parched Texas has filed suit against New Mexico in multiple jurisdictions, including the Supreme Court, to force the state to send more water downstream — water it doesn’t have. Texas has already appropriated $5 million to litigate the matter. If it wins, the hit taken by agriculture in south-central New Mexico could be disastrous.

In eastern New Mexico, the woes of the Pecos River mirror those of the Rio Grande and pit the Pecos basin’s two largest cities, Carlsbad and Roswell, directly against each other. These days, the only thing moving in the irrigation canals of the Carlsbad Irrigation District is dust. The canals are bone dry because upstream groundwater pumping in the Roswell area has deprived the Pecos River of its flow. By pumping heavily from wells that tap the aquifer under the Pecos River, Roswell’s farmers have drawn off water that might otherwise find its way to the surface and flow downstream.

Carlsbad’s water rights are senior to (that is, older than) Roswell’s, so in theory — under the doctrine of Prior Appropriation — Carlsbad is entitled to the water Roswell is using. The dispute pits Carlsbad’s substantial agricultural economy against Roswell’s, which is twice as big. The bottom line, as with Texas’s lawsuit over the Rio Grande, is that there simply isn’t enough water to go around.

If you want to put your money on one surefire bet in the Southwest, it’s this: one way or another, however these or any other onrushing disputes turn out, large numbers of farmers are going to go out of business.

Put on Your Rain-Dancing Shoes

New Mexico’s present struggles, difficult as they may be, will look small-scale indeed when compared to what will eventually befall the Colorado. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation expects the river’s 40 million water-users to grow to between 49.3 and 76.5 million by 2060. This translates into a thirst for Colorado River water of 18.1 to 20.4 maf — oceans more than its historical yield of 16.4 maf.

And that’s not even the bad news, which is that, compared to the long-term paleo-record, the historical average, compiled since the late nineteenth century, is aberrantly high. Moreover, climate change will undoubtedly take its toll, and perhaps has already begun to do so. One recent study forecasts that the yield of the Colorado will decline 10% by about 2030, and it will keep falling after that.

None of the available remedies inspires much confidence. “Augmentation” — diverting water from another basin into the Colorado system — is politically, if not economically, infeasible. Desalination, which can be effective in specific, local situations, is too expensive and energy-consuming to slake much of the Southwest’s thirst. Weather modification, aka rain-making, isn’t much more effective today than it was in 1956 when Burt Lancaster starred as a water-witching con man in The Rainmaker, and vegetation management (so that trees and brush will consume less water) is a non-starter when climate change and epidemic fires are already reworking the landscape.

Undoubtedly, there will be small successes squeezing water from unlikely sources here and there, but the surest prospect for the West? That a bumper harvest of lawsuits is approaching. Water lawyers in the region can look forward to full employment for decades to come. Their clients will include irrigation farmers, thirsty cities, and power companies that need water to cool their thermal generators and to drive their hydroelectric generators.

Count on it: the recreation industry, which demands water for boating and other sports, will be filing its briefs, too, as will environmental groups struggling to prevent endangered species and whole ecosystems from blinking out. The people of the West will not only watch them; they — or rather, we — will all in one way or another be among them as they gather before various courts in the legal equivalent of circular firing squads.

Hey, Mister, What’s that Sound?

Here at the bottom of Grand Canyon, with the river rushing by, we listen for the boom of the downstream rapids toward which we are headed. Sometimes they sound like a far-off naval bombardment, sometimes more like the roar of an oncoming freight train, which is entirely appropriate. After all, the river, like a railroad, is a delivery system with a valuable cargo. Think of it as a stream of liquid property, every pint within it already spoken for, every drop owned by someone and obligated somewhere, according to a labyrinth of potentially conflicting contracts.

The owners of those contracts know now that the river can’t supply enough gallons, pints, and drops to satisfy everybody, and so they are bound to live the truth of the old western saying: “Whiskey’s for drinkin’, and water’s for fightin’.”

In the end, Powell was right about at least one thing: aridity bats last.

William deBuys, a TomDispatch regular, irrigates a small farm in northern New Mexico and is the author of seven books including, most recently, A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest.

Copyright 2013 William deBuys

If readers will forgive me, I will continue the theme tomorrow with a rather more personal perspective.