Photographs of the family of geese in our pond in Hugo Road, Oregon.

oooo

oooo

oooo

In the last few days the whole family have winged it elsewhere.

They were gorgeous!

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Category: Water

Two shots of this beautiful lake.

I was going through some files yesterday and found many photographs taken by me.

oooo

These were taken in 2018 which was when my son, Alex, and his partner, Lisa, came over to see us.

Here is the opening part of Wikipedia writing about Crater Lake:

Crater Lake (Klamath: Giiwas)[2] is a volcanic crater lake in south-central Oregon in the Western United States. It is the main feature of Crater Lake National Park and is a tourist attraction for its deep blue color and water clarity. The lake partly fills a 2,148-foot-deep (655 m) caldera[3] that was formed around 7,700 (± 150) years ago[4] by the collapse of the volcano Mount Mazama. No rivers flow into or out of the lake; the evaporation is compensated for by rain and snowfall at a rate such that the total amount of water is replaced every 150 years.[5] With a depth of 1,949 feet (594 m),[6] the lake is the deepest in the United States. In the world, it ranks eleventh for maximum depth, as well as fifth for mean depth.

The rest of that Wikipedia article is here.

Namely a universal law.

I was attracted to an article that I read in The Conversation last a week ago.

It also taught me that we humans speak according to Zipf’s Law. I had not previously heard of this law.

So let me republish the article with the full permission of The Conversation.

ooOOoo

Jenny Allen, Griffith University; Ellen Garland, University of St Andrews; Inbal Arnon, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Simon Kirby, University of Edinburgh

All known human languages display a surprising pattern: the most frequent word in a language is twice as frequent as the second most frequent, three times as frequent as the third, and so on. This is known as Zipf’s law.

Researchers have hunted for evidence of this pattern in communication among other species, but until now no other examples have been found.

In new research published today in Science, our team of experts in whale song, linguistics and developmental psychology analysed eight years’ of song recordings from humpback whales in New Caledonia. Led by Inbal Arnon from the Hebrew University, Ellen Garland from the University of St Andrews, and Simon Kirby from the University of Edinburgh, We used techniques inspired by the way human infants learn language to analyse humpback whale song.

We discovered that the same Zipfian pattern universally found across human languages also occurs in whale song. This complex signalling system, like human language, is culturally learned by each individual from others.

When infant humans are learning, they have to somehow discover where words start and end. Speech is continuous and does not come with gaps between words that they can use. So how do they break into language?

Thirty years of research has revealed that they do this by listening for sounds that are surprising in context: sounds within words are relatively predictable, but between words are relatively unpredictable. We analysed the whale song data using the same procedure.

Unexpectedly, using this technique revealed in whale song the same statistical properties that are found in all languages. It turns out both human language and whale song have statistically coherent parts.

In other words, they both contain recurring parts where the transitions between elements are more predictable within the part. Moreover, these recurring sub-sequences we detected follow the Zipfian frequency distribution found across all human languages, and not found before in other species.

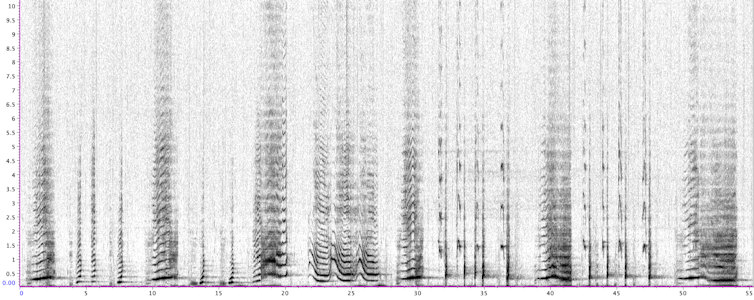

Whale song recording (2017) Operation Cetaces 916 KB (download)

How do the same statistical properties arise in two evolutionarily distant species that differ from one another in so many ways? We suggest we found these similarities because humans and whales share a learning mechanism: culture.

Our findings raise an exciting question: why would such different systems in such incredibly distant species have common structures? We suggest the reason behind this is that both are culturally learned.

Cultural evolution inevitably leads to the emergence of properties that make learning easier. If a system is hard to learn, it will not survive to the next generation of learners.

There is growing evidence from experiments with humans that having statistically coherent parts, and having them follow a Zipfian distribution, makes learning easier. This suggests that learning and transmission play an important role in how these properties emerged in both human language and whale song.

Finding parallel structures between whale song and human language may also lead to another question: can we talk to whales now? The short answer is no, not at all.

Our study does not examine the meaning behind whale song sequences. We have no idea what these segments might mean to the whales, if they mean anything at all.

It might help to think about it like instrumental music, as music also contains similar structures. A melody can be learned, repeated, and spread – but that doesn’t give meaning to the musical notes in the same way that individual words have meaning.

Our work also makes a bold prediction: we should find this Zipfian distribution wherever complex communication is transmitted culturally. Humans and whales are not the only species that do this.

We find what is known as “vocal production learning” in an unusual range of species across the animal kingdom. Song birds in particular may provide the best place to look as many bird species culturally learn their songs, and unlike in whales, we know a lot about precisely how birds learn song.

Equally, we expect not to find these statistical properties in the communication of species that don’t transmit complex communication by learning. This will help to reveal whether cultural evolution is the common driver of these properties between humans and whales.

Jenny Allen, Postdoctoral research associate, Griffith University; Ellen Garland, Royal Society University Research Fellow, School of Biology, University of St Andrews; Inbal Arnon, Professor of Psychology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Simon Kirby, Professor of Language Evolution, University of Edinburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

The research scientists have led to a prediction: … we should find this Zipfian distribution wherever complex communication is transmitted culturally. Humans and whales are not the only species that do this.

Fascinating!

Last Monday’s snow, as in the 3rd February, 2025.

oooo

oooo

The first two were taken on our deck, looking East, and the third was taken from my office window looking to the South.

Update as of Wednesday last!

oooo

oooo

oooo

My guess is that we are now experiencing some 8 inches of snow!

Then an update from last Friday afternoon.

Mount Sexton, above and below.

oooo

And I want to return to publishing posts!

My last post was about an accident that I had on the 17th November, last.

Jean is now back home; she came home on Friday, 13th December. However, every day we have a caregiver at home for part of the time. Jean is getting slowly better. I would estimate that at about one percent a day.

I am unsure as to the pattern of my posts. Whether I should go back to scheduling posts three times a week or publish posts on an ad-hoc basis. That will become clearer over the next few weeks.

I am going to start with publishing posts on an ad-hoc basis.

Meanwhile here in Merlin we have had loads of rain.

This is the creek that flows across the lower part of the property.