Note: This is a long and pretty depressing post yet one that contains a critically vital message. Just wanted to flag that up.

This is not the first time I have used this expression as a header to a blogpost. The first time was back in August 2013 when I introduced the TomDispatch essay: Rebecca Solnit, The Age of Inhuman Scale.

I am using it again to introduce another TomDispatch essay. Like the Solnit essay a further reflection on the incredible madness of these present global times.

However, I find the malaise gripping us in these times to be infinitely more difficult to understand than what is or is not mathematically possible. I just can’t get my mind around the possibility that we are in an era where greed, inequality and the pursuit of power and money will take the whole of humanity over the edge.

I highlighted the name ExxonMobil in that extract because that company is the subject of Tom Engelhardt’s essay from Bill McKibben. Republished here with Tom’s kind permission.

The time scale should stagger you. Just imagine for a moment that what we humans do on this planet will last at least 10,000 more years, and no, I’m not talking about those statues on Easter Island or the pyramids or the Great Wall of China or the Empire State Building. I’m not talking about any of our monumental architectural-cum-artistic achievements. Ten thousand years from now all the monuments to our history may be forgotten ruins or simply obliterated, while what we’re doing at this very moment that’s truly ruinous may outlast us all. I’m thinking, of course, about the burning of fossil fuels and the sending of carbon dioxide (and other greenhouse gases) into the atmosphere. It’s becoming clearer by the month that, if not brought under control relatively quickly, this process will alter the global environment in ways that will affect humanity and everything else living on this planet for what, from a human point of view, is eternity.

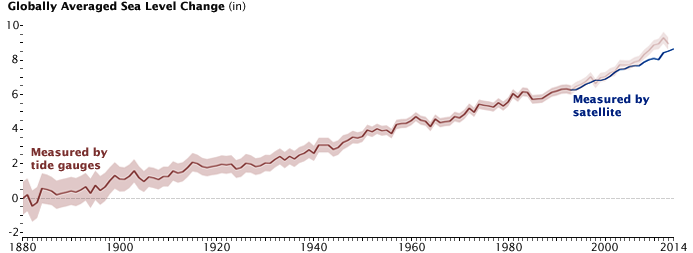

In essence, there’s no backsies when it comes to climate change. Once you’ve begun the full-scale destabilization and melting of the Greenland ice sheet and of the vast ice sheets in the Antarctic, for instance, the future inundation of coastal areas, including many of humanity’s major cities, is a foregone conclusion somewhere down the line. In fact, a recent study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change by 22 climate scientists, suggests that when it comes to the melting of ice sheets and the rise of seas and oceans, we’re not just talking about how life will be changed on Planet Earth in 2100 or even 2200. We’re potentially talking about what it will be like in 12,200, an expanse of time twice as long as human history to date. So many thousands of years are hard even to fathom, but as the study points out, “A considerable fraction of the carbon emitted to date and in the next 100 years will remain in the atmosphere for tens to hundreds of thousands of years.” The essence of the report, as Chris Mooney wrote in the Washington Post, is this: “In 10,000 years, if we totally let it rip, the planet could ultimately be an astonishing 7 degrees Celsius warmer on average and feature seas 52 meters (170 feet) higher than they are now.”

Even far more modest temperature changes like the two degree Celsius rise discussed at the recent Paris meeting, where 196 nations signed onto a climate change agreement, would transform the face of the planet for thousands of years and result in the drowning of a range of iconic global cities “including New York, London, Rio de Janeiro, Cairo, Calcutta, Jakarta, and Shanghai.”

This, in other words, is what the hunt for yet more fossil fuels and more profits by the planet’s giant energy companies actually means — not tomorrow, but on a scale we don’t usually consider. This is why those who continue to insist on pursuing such a treasure hunt (for a few companies and their shareholders), despite knowing its grim future results, will truly be in the running with some of the monsters of our past to become the ultimate criminals of history. In this light, consider what Bill McKibben, TomDispatch regular, founder of 350.org, and author most recently of Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist, has to say about one of those companies, ExxonMobil, and its pivotal role in our warming world. Tom

Exxon’s Never-Ending Big Dig

Flooding the Earth With Fossil Fuels

By Bill McKibben

Here’s the story so far. We have the chief legal representatives of the eighth and 16th largest economies on Earth (California and New York) probing the biggest fossil fuel company on Earth (ExxonMobil), while both Democratic presidential candidates are demanding that the federal Department of Justice join the investigation of what may prove to be one of the biggest corporate scandals in American history. And that’s just the beginning. As bad as Exxon has been in the past, what it’s doing now — entirely legally — is helping push the planet over the edge and into the biggest crisis in the entire span of the human story.

Back in the fall, you might have heard something about how Exxon had covered up what it knew early on about climate change. Maybe you even thought to yourself: that doesn’t surprise me. But it should have. Even as someone who has spent his life engaged in the bottomless pit of greed that is global warming, the news and its meaning came as a shock: we could have avoided, it turns out, the last quarter century of pointless climate debate.

The results of all that work were unequivocal. By 1982, in an internal “corporate primer,” Exxon’s leaders were told that, despite lingering unknowns, dealing with climate change “would require major reductions in fossil fuel combustion.” Unless that happened, the primer said, citing independent experts, “there are some potentially catastrophic events that must be considered… Once the effects are measurable, they might not be reversible.” But that document, “given wide circulation” within Exxon, was also stamped “Not to be distributed externally.”

So here’s what happened. Exxon used its knowledge of climate change to plan its own future. The company, for instance, leased large tracts of the Arctic for oil exploration, territory where, as a company scientist pointed out in 1990, “potential global warming can only help lower exploration and development costs.” Not only that but, “from the North Sea to the Canadian Arctic,” Exxon and its affiliates set about “raising the decks of offshore platforms, protecting pipelines from increasing coastal erosion, and designing helipads, pipelines, and roads in a warming and buckling Arctic.” In other words, the company started climate-proofing its facilities to head off a future its own scientists knew was inevitable.

But in public? There, Exxon didn’t own up to any of this. In fact, it did precisely the opposite. In the 1990s, it started to put money and muscle into obscuring the science around climate change. It funded think tanks that spread climate denial and even recruited lobbying talent from the tobacco industry. It also followed the tobacco playbook when it came to the defense of cigarettes by highlighting “uncertainty” about the science of global warming. And it spent lavishly to back political candidates who were ready to downplay global warming.

Its CEO, Lee Raymond, even traveled to China in 1997 and urged government leaders there to go full steam ahead in developing a fossil fuel economy. The globe was cooling, not warming, he insisted, while his engineers were raising drilling platforms to compensate for rising seas. “It is highly unlikely,” he said, “that the temperature in the middle of the next century will be significantly affected whether policies are enacted now or 20 years from now.” Which wasn’t just wrong, but completely and overwhelmingly wrong — as wrong as a man could be.

Sins of Omission

In fact, Exxon’s deceit — its ability to discourage regulations for 20 years — may turn out to be absolutely crucial in the planet’s geological history. It’s in those two decades that greenhouse gas emissions soared, as did global temperatures until, in the twenty-first century, “hottest year ever recorded” has become a tired cliché. And here’s the bottom line: had Exxon told the truth about what it knew back in 1990, we might not have wasted a quarter of a century in a phony debate about the science of climate change, nor would anyone have accused Exxon of being “alarmist.” We would simply have gotten to work.

But Exxon didn’t tell the truth. A Yale study published last fall in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed that money from Exxon and the Koch Brothers played a key role in polarizing the climate debate in this country.

The company’s sins — of omission and commission — may even turn out to be criminal. Whether the company “lied to the public” is the question that New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman decided to investigate last fall in a case that could make him the great lawman of our era if his investigation doesn’t languish. There are various consumer fraud statutes that Exxon might have violated and it might have failed to disclose relevant information to investors, which is the main kind of lying that’s illegal in this country of ours. Now, Schneiderman’s got backup from California Attorney General Kamala Harris, and maybe — if activists continue to apply pressure — from the Department of Justice as well, though its highly publicized unwillingness to go after the big banks does not inspire confidence.

Here’s the thing: all that was bad back then, but Exxon and many of its Big Energy peers are behaving at least as badly now when the pace of warming is accelerating. And it’s all legal — dangerous, stupid, and immoral, but legal.

On the face of things, Exxon has, in fact, changed a little in recent years.

For one thing, it’s stopped denying climate change, at least in a modest way. Rex Tillerson, Raymond’s successor as CEO, stopped telling world leaders that the planet was cooling. Speaking in 2012 at the Council on Foreign Relations, he said, “I’m not disputing that increasing CO2 emissions in the atmosphere is going to have an impact. It’ll have a warming impact.”

As a start, investigations by the Pulitzer-Prize winning Inside Climate News, the Los Angeles Times, and Columbia Journalism School revealed in extraordinary detail that Exxon’s top officials had known everything there was to know about climate change back in the 1980s. Even earlier, actually. Here’s what senior company scientist James Black told Exxon’s management committee in 1977: “In the first place, there is general scientific agreement that the most likely manner in which mankind is influencing the global climate is through carbon dioxide release from the burning of fossil fuels.” To determine if this was so, the company outfitted an oil tanker with carbon dioxide sensors to measure concentrations of the gas over the ocean, and then funded elaborate computer models to help predict what temperatures would do in the future.

Of course, he immediately went on to say that its impact was uncertain indeed, hard to estimate, and in any event entirely manageable. His language was striking. “We will adapt to this. Changes to weather patterns that move crop production areas around — we’ll adapt to that. It’s an engineering problem, and it has engineering solutions.”

Add to that gem of a comment this one: the real problem, he insisted, was that “we have a society that by and large is illiterate in these areas, science, math, and engineering, what we do is a mystery to them and they find it scary. And because of that, it creates easy opportunities for opponents of development, activist organizations, to manufacture fear.”

Right. This was in 2012, within months of floods across Asia that displaced tens of millions and during the hottest summer ever recorded in the United States, when much of our grain crop failed. Oh yeah, and just before Hurricane Sandy.

He’s continued the same kind of belligerent rhetoric throughout his tenure. At last year’s ExxonMobil shareholder meeting, for instance, he said that if the world had to deal with “inclement weather,” which “may or may not be induced by climate change,” we should employ unspecified “new technologies.” Mankind, he explained, “has this enormous capacity to deal with adversity.”

In other words, we’re no longer talking about outright denial, just a denial that much really needs to be done. And even when the company has proposed doing something, its proposals have been strikingly ethereal. Exxon’s PR team, for instance, has discussed supporting a price on carbon, which is only what economists left, right, and center have been recommending since the 1980s. But the minimal price they recommend — somewhere in the range of $40 to $60 a ton — wouldn’t do much to slow down their business. After all, they insist that all their reserves are still recoverable in the context of such a price increase, which would serve mainly to make life harder for the already terminal coal industry.

But say you think it’s a great idea to put a price on carbon — which, in fact, it is, since every signal helps sway investment decisions. In that case, Exxon’s done its best to make sure that what they pretend to support in theory will never happen in practice.

Consider, for instance, their political contributions. The website Dirty Energy Money, organized by Oil Change International, makes it easy to track who gave what to whom. If you look at all of Exxon’s political contributions from 1999 to the present, a huge majority of their political harem of politicians have signed the famous Taxpayer Protection Pledge from Grover Norquist’s Americans for Tax Reform that binds them to vote against any new taxes. Norquist himself wrote Congress in late January that “a carbon tax is a VAT or Value Added Tax on training wheels. Any carbon tax would inevitably be spread out over wider and wider parts of the economy until we had a European Value Added Tax.” As he told a reporter last year, “I don’t see the path to getting a lot of Republican votes” for a carbon tax, and since he’s been called “the most powerful man in American politics,” that seems like a good bet.

The only Democratic senator in Exxon’s top 60 list was former Louisiana solon Mary Landrieu, who made a great virtue in her last race of the fact that she was “the key vote” in blocking carbon pricing in Congress. Bill Cassidy, the man who defeated her, is also an Exxon favorite, and lost no time in co-sponsoring a bill opposing any carbon taxes. In other words, you could really call Exxon’s supposed concessions on climate change a Shell game. Except it’s Exxon.

The Never-Ending Big Dig

Even that’s not the deepest problem.

The deepest problem is Exxon’s business plan. The company spends huge amounts of money searching for new hydrocarbons. Given the recent plunge in oil prices, its capital spending and exploration budget was indeed cut by 12% in 2015 to $34 billion, and another 25% in 2016 to $23.2 billion. In 2015, that meant Exxon was spending $63 million a day “as it continues to bring new projects on line.” They are still spending a cool $1.57 billion a year looking for new sources of hydrocarbons — $4 million a day, every day.

As Exxon looks ahead, despite the current bargain basement price of oil, it still boasts of expansion plans in the Gulf of Mexico, eastern Canada, Indonesia, Australia, the Russian far east, Angola, and Nigeria. “The strength of our global organization allows us to explore across all geological and geographical environments, using industry-leading technology and capabilities.” And its willingness to get in bed with just about any regime out there makes it even easier. Somewhere in his trophy case, for instance, Rex Tillerson has an Order of Friendship medal from one Vladimir Putin. All it took was a joint energy venture estimated to be worth $500 billion.

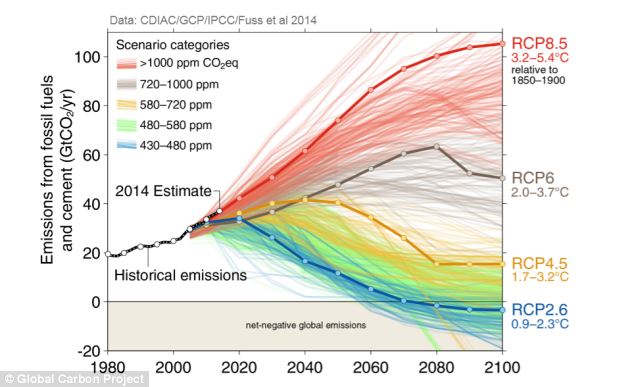

But, you say, that’s what oil companies do, go find new oil, right? Unfortunately, that’s precisely what we can’t have them doing any more. About a decade ago, scientists first began figuring out a “carbon budget” for the planet — an estimate for how much more carbon we could burn before we completely overheated the Earth. There are potentially many thousands of gigatons of carbon that could be extracted from the planet if we keep exploring. The fossil fuel industry has already identified at least 5,000 gigatons of carbon that it has told regulators, shareholders, and banks it plans to extract. However, we can only burn about another 900 gigatons of carbon before we disastrously overheat the planet. On our current trajectory, we’d burn through that “budget” in about a couple of decades. The carbon we’ve burned has already raised the planet’s temperature a degree Celsius, and on our present course we’ll burn enough to take us past two degrees in less than 20 years.

At this point, in fact, no climate scientist thinks that even a two-degree rise in temperature is a safe target, since one degree is already melting the ice caps. (Indeed, new data released this month shows that, if we hit the two-degree mark, we’ll be living with drastically raised sea levels for, oh, twice as long as human civilization has existed to date.) That’s why in November world leaders in Paris agreed to try to limit the planet’s temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius, or just under three degrees Fahrenheit. If you wanted to meet that target, however, you would need to be done burning fossil fuels by perhaps 2020, which is in technical terms just about now.

That’s why it’s wildly irresponsible for a company to be leading the world in oil exploration when, as scientists have carefully explained, we already have access to four or five times as much carbon in the Earth as we can safely burn. We have it, as it were, on the shelf. So why would we go looking for more? Scientists have even done us the useful service of identifying precisely the kinds of fossil fuels we should never dig up, and — what do you know — an awful lot of them are on Exxon’s future wish list, including the tar sands of Canada, a particularly carbon-filthy, environmentally destructive fuel to produce and burn.

Even Exxon’s one attempt to profit from stanching global warming has started to come apart. Several years ago, the company began a calculated pivot in the direction of natural gas, which produces less carbon than oil when burned. In 2009, Exxon acquired XTO Energy, a company that had mastered the art of extracting gas from shale via hydraulic fracturing. By now, Exxon has become America’s leading fracker and a pioneer in natural gas markets around the world. The trouble with fracked natural gas — other than what Tillerson once called “farmer Joe’s lit his faucet on fire” — is this: in recent years, it’s become clear that the process of fracking for gas releases large amounts of methane into the atmosphere, and methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. As Cornell University scientist Robert Howarth has recently established, burning natural gas to produce electricity probably warms the planet faster than burning coal or crude oil.

Exxon’s insistence on finding and producing ever more fossil fuels certainly benefited its shareholders for a time, even if it cost the Earth dearly. Five of the 10 largest annual profits ever reported by any company belonged to Exxon in these years. Even the financial argument is now, however, weakening. Over the last five years, Exxon has lagged behind many of its competitors as well as the broader market, and a big reason, according to the Carbon Tracker Initiative (CTI), is its heavy investment in particularly expensive, hard-to-recover oil and gas.

In 2007, as CTI reported, Canadian tar sands and similar “heavy oil” deposits accounted for 7.5% of Exxon’s proven reserves. By 2013, that number had risen to 17%. A smart business strategy for the company, according to CTI, would involve shrinking its exploration budget, concentrating on the oil fields it has access to that can still be pumped profitably at low prices, and using the cash flow to buy back shares or otherwise reward investors.

That would, however, mean exchanging Exxon’s Texan-style big-is-good approach for something far more modest. And since we’re speaking about what was the biggest company on the planet for a significant part of the twentieth century, Exxon seems to be set on continuing down that bigger-is-better path. They’re betting that the price of oil will rise in the reasonably near future, that alternative energy won’t develop fast enough, and that the world won’t aggressively tackle climate change. And the company will keep trying to cover those bets by aggressively backing politicians capable of ensuring that nothing happens.

Can Exxon Be Pressured?

Next to that fierce stance on the planet’s future, the mild requests of activists for the last 25 years seem… well, next to pointless. At the 2015 ExxonMobil shareholder meeting, for instance, religious shareholder activists asked for the umpteenth time that the company at least make public its plans for managing climate risks. Even BP, Shell, and Statoil had agreed to that much. Instead, Exxon’s management campaigned against the resolution and it got only 9.6% of shareholder votes, a tally so low it can’t even be brought up again for another three years. By which time we’ll have burned through… oh, never mind.

What we need from Exxon is what they’ll never give: a pledge to keep most of their reserves underground, an end to new exploration, and a promise to stay away from the political system. Don’t hold your breath.

But if Exxon seems hopelessly set in its ways, revulsion is growing. The investigations by the New York and California attorneys general mean that the company will have to turn over lots of documents. If journalists could find out as much as they did about Exxon’s deceit in public archives, think what someone with subpoena power might accomplish. Many other jurisdictions could jump in, too.

At the Paris climate talks in December, a panel of law professors led a well-attended session on the different legal theories that courts around the world might apply to the company’s deceptive behavior. When that begins to happen, count on one thing: the spotlight won’t shine exclusively on Exxon. As with the tobacco companies in the decades when they were covering up the dangers of cigarettes, there’s a good chance that the Big Energy companies were in this together through their trade associations and other front groups. In fact, just before Christmas, Inside Climate Newspublished some revealing new documents about the role that Texaco, Shell, and other majors played in an American Petroleum Institute study of climate change back in the early 1980s. A trial would be a transformative event — a reckoning for the crime of the millennium.

But while we’re waiting for the various investigations to play out, there’s lots of organizing going at the state and local level when it comes to Exxon, climate change, and fossil fuels — everything from politely asking more states to join the legal process to politely shutting down gas stations for a few hours to pointing out to New York and California that they might not want to hold millions of dollars of stock in a company they’re investigating. It may even be starting to work.

Vermont Governor Peter Shumlin, for instance, singled Exxon out in his state of the state address last month. He called on the legislature to divest the state of its holdings in the company because of its deceptions. “This is a page right out of Big Tobacco,” he said, “which for decades denied the health risks of their product as they were killing people. Owning ExxonMobil stock is not a business Vermont should be in.”

The question is: Why on God’s-not-so-green-Earth-anymore would anyone want to be Exxon’s partner?

Bill McKibben, a TomDispatch regular, is the founder of 350.org and Schumann Distinguished Scholar at Middlebury College. He was the 2014 recipient of the Right Livelihood Award, often called the “alternative Nobel Prize.” His most recent book is Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Nick Turse’s Tomorrow’s Battlefield: U.S. Proxy Wars and Secret Ops in Africa, and Tom Engelhardt’s latest book, Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.

Copyright 2016 Bill McKibben

ooOOoo

Let me close this tale of modern madness with the closing words from Patrice’s essay:

American plutocrats are always one step ahead of the propaganda game. After spending decades claiming the Earth was not warming, now they are pretending, thanks to this impossible blue graph, that we stop the deleterious effects on the biosphere on a dime, should the USA want it.

And the scientists are playing along… because they want the money. And the influence. And the plutocrats in the audience. And the American population confusedly feel that the USA is better off with cheap gas.

As I explained, the Moral Imperative is to think correctly, and the first imperative of scientists should be to teach what is impossible. It’s impossible to stop the nefarious effects on the biosphere on a dime. There is huge inertia in the world climate and geophysics. Right now, climate change is happening at a rate 100,000 times the rate of the preceding great extinctions (they probably had to do with huge, sustained volcanism, direct from the core).

In the best scenario of business as usual, most of energy from fossil fuels, we are on 4 degree Centigrade global warming scenario. And that means the poles will melt entirely. That will make the present Middle East disarray feel as if it had been a walk in a pleasant park.

Patrice Ayme’

Pure unadulterated madness! And I feel utterly powerless to stop it!

To be sure, many people live in cities and work at jobs where living without a car is virtually impossible — and these are the people who this report is written for.

To be sure, many people live in cities and work at jobs where living without a car is virtually impossible — and these are the people who this report is written for.

Sivak and Schoettle also suggest that we all try reducing our collective caloric input by 1 percent, eating 25 fewer calories a day (if we’re men) or 20 fewer a day (for women) — about

Sivak and Schoettle also suggest that we all try reducing our collective caloric input by 1 percent, eating 25 fewer calories a day (if we’re men) or 20 fewer a day (for women) — about