The latest essay from Tom Engelhardt!

You all know that for a great percentage of my time I write about dogs and republish other articles about dogs.

For dogs are precious. Dogs are sensitive. Dogs read us humans. Dogs play. They sleep. And much more!

But just occasionally I like to republish an essay from Tom Engelhardt.

Maybe because years ago he gave me blanket permission to republish his essays. Maybe because he and I are more or less the same age. Maybe because in my more quieter, introspective moments I wonder where the hell we are going. And Tom seems to agree.

Have a read of this.

ooOOoo

Tomgram: Engelhardt, The Unexpected Past, the Unknown Future

Posted by Tom Engelhardt at 3:50pm, August 9, 2020.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter @TomDispatch.

[Note for TomDispatch Readers: Even in this terrible moment, TD does its best to continue offering an alternate view of this increasingly strange planet of ours. And I can only do so because of the ongoing support of readers. (I just wish I could actually thank each of you individually!) If you have the urge to continue to lend a hand in keeping TomDispatch afloat, then do check out our donation page. For a donation of $100 ($125 if you live outside the U.S.), I usually offer a signed, personalized book from one of a number of TD authors listed on that page and you can certainly ask, but no guarantees in this pandemic moment. Still, you really do make all the difference and I can’t thank you enough for that! Tom]

It Could Have Been Different

My World and (Unfortunately) Welcome to It

By Tom Engelhardt

Let me be blunt. This wasn’t the world I imagined for my denouement. Not faintly. Of course, I can’t claim I ever really imagined such a place. Who, in their youth, considers their death and the world that might accompany it, the one you might leave behind for younger generations? I’m 76 now. True, if I were lucky (or perhaps unlucky), I could live another 20 years and see yet a newer world born. But for the moment at least, it seems logical enough to consider this pandemic nightmare of a place as the country of my old age, the one that I and my generation (including a guy named Donald J. Trump) will pass on to our children and grandchildren.

Back in 2001, after the 9/11 attacks, I knew it was going to be bad. I felt it deep in my gut almost immediately and, because of that, stumbled into creating TomDispatch.com, the website I still run. But did I ever think it would be this bad? Not a chance.

I focused back then on what already looked to me like a nightmarish American imperial adventure to come, the response to the 9/11 attacks that the administration of President George W. Bush quickly launched under the rubric of “the Global War on Terror.” And that name (though the word “global” would soon be dropped for the more anodyne “war on terror”) would prove anything but inaccurate. After all, in those first post-9/11 moments, the top officials of that administration were thinking as globally as possible when it came to war. At the damaged Pentagon, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld almost immediately turned to an aide and told him, “Go massive — sweep it all up, things related and not.” From then on, the emphasis would always be on the more the merrier.

Bush’s top officials were eager to take out not just Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda, whose 19 mostly Saudi hijackers had indeed attacked this country in the most provocative manner possible (at a cost of only $400,000-$500,000), but the Taliban, too, which then controlled much of Afghanistan. And an invasion of that country was seen as but the initial step in a larger, deeply desired project reportedly meant to target more than 60 countries! Above all, George W. Bush and his top officials dreamed of taking down Iraqi autocrat Saddam Hussein, occupying his oil-rich land, and making the United States, already the unipolar power of the twenty-first century, the overseer of the Greater Middle East and, in the end, perhaps even of a global Pax Americana. Such was the oil-fueled imperial dreamscape of George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and crew (including that charmer and now bestselling anti-Trump author John Bolton).

Who Woulda Guessed?

In the years that followed, I would post endless TomDispatch pieces, often by ex-military men, focused on the ongoing nightmare of our country’s soon-to-become forever wars (without a “pax” in sight) and the dangers such spreading conflicts posed to our world and even to us. Still, did I imagine those wars coming home in quite this way? Police forces in American cities and towns thoroughly militarized right down to bayonets, MRAPs, night-vision goggles, and helicopters, thanks to a Pentagon program delivering equipment to police departments nationwide more or less directly off the battlefields of Washington’s never-ending wars? Not for a moment.

Who doesn’t remember those 2014 photos of what looked like an occupying army on the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, after the police killing of a Black teenager and the protests that followed? And keep in mind that, to this day, the Republican Senate and the Trump administration have shown not the slightest desire to rein in that Pentagon program to militarize police departments nationwide. Such equipment (and the mentality that goes with it) showed up strikingly on the streets of American cities and towns during the recent Black Lives Matter protests.

Even in 2014, however, I couldn’t have imagined federal agents by the hundreds, dressed as if for a forever-war battlefield, flooding onto those same streets (at least in cities run by Democratic mayors), ready to treat protesters as if they were indeed al-Qaeda (“VIOLENT ANTIFA ANARCHISTS”), or that it would all be part of an election ploy by a needy president. Not a chance.

Or put another way, a president with his own “goon squad” or “stormtroopers” outfitted to look as if they were shipping out for Afghanistan or Iraq but heading for Portland, Albuquerque, Chicago, Seattle, and other American cities? Give me a break! How un-American could you get? A military surveillance drone overhead in at least one of those cities as if this were someone else’s war zone? Give me a break again. Never in my wildest dreams did I think I’d live to witness anything quite like it or a president — and we’ve had a few doozies — even faintly like the man a minority of deeply disgruntled Americans but a majority of electors put in the White House in 2016 to preside over a failing empire.

How about an American president in the year 2020 as a straightforward, no-punches-pulled racist, the sort of guy a newspaper could compare to former segregationist Alabama governor and presidential candidate George Wallace without even blinking? Admittedly, in itself, presidential racism has hardly been unique to this moment in America, despite Joe Biden’s initial claim to the contrary. That couldn’t be the case in the country in which Woodrow Wilson made D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, the infamous silent movie in which the Ku Klux Klan rides to the rescue, the first film ever to be shown in the White House; nor the one in which Richard Nixon used his “Southern strategy” — Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater had earlier labeled it even more redolently “Operation Dixie” — to appeal to the racist fears of Southern whites and so begin to turn that region from a Democratic stronghold into a Republican bastion; nor in the land where Ronald Reagan launched his election campaign of 1980 with a “states’ rights” speech (then still a code phrase for segregation) near Philadelphia, Mississippi, just miles from the earthen dam where three murdered civil rights workers had been found buried in 1964.

Still, an openly racist president (don’t take that knee!) as an autocrat-in-the-making (or at least in-the-dreaming), one who first descended that Trump Tower escalator in 2015 denouncing Mexican “rapists,” ran for president rabidly on a Muslim ban, and for whom Black lives, including John Lewis’s, have always been immaterial, a president now defending every Confederate monument and military base named after a slave-owning general in sight, while trying to launch a Nixon-style “law and (dis)order” campaign? I mean, who woulda thunk it?

And add to that the once unimaginable: a man without an ounce of empathy in the White House, a figure focused only on himself and his electoral and pecuniary fate (and perhaps those of his billionaire confederates); a man filling his hated “deep state” with congressionally unapproved lackies, flacks, and ass-kissers, many of them previously flacks (aka lobbyists) for major corporations. (Note, by the way, that while The Donald has a distinctly autocratic urge, I don’t describe him as an incipient fascist because, as far as I can see, his sole desire — as in those now-disappeared rallies of his — is to have fans, not lead an actual social movement of any sort. Think of him as Mussolini right down to the look and style with a “base” of cheering MAGA chumps but no urge for an actual fascist movement to lead.)

And who ever imagined that an American president might actually bring up the possibility of delaying an election he fears losing, while denouncing mail-in ballots (“the scandal of our time”) as electoral fraud and doing his damnedest to undermine the Post Office which would deliver them amid an economic downturn that rivals the Great Depression? Who, before this moment, ever imagined that a president might consider refusing to leave the White House even if he did lose his reelection bid? Tell me this doesn’t qualify as something new under the American sun. True, it wasn’t Donald Trump who turned this country’s elections into 1% affairs or made contributions by the staggeringly wealthy and corporations a matter of free speech (thank you, Supreme Court!), but it is Donald Trump who is threatening, in his own unique way, to make elections themselves a thing of the past. And that, believe me, I didn’t count on.

Nor did I conceive of an all-American world of inequality almost beyond imagining. A country in which only the truly wealthy (think tax cuts) and the national security state (think budgets eternally in the stratosphere) are assured of generous funding in the worst of times.

The World to Come?

Oh, and I haven’t even mentioned the pandemic yet, have I? The one that should bring to mind the Black Death of the fourteenth century and the devastating Spanish Flu of a century ago, the one that’s killing Americans in remarkable numbers daily and going wild in this country, aided and abetted in every imaginable way (and some previously unimaginable ones) by the federal government and the president. Who could have dreamed of such a disease running riot, month after month, in the wealthiest, most powerful country on the planet without a national plan for dealing with it? Who could have dreamed of the planet’s most exceptional, indispensable country (as its leaders once loved to call it) being unable to take even the most modest steps to rein in Covid-19, thanks to a president, Republican governors, and Republican congressional representatives who consider science the equivalent of alien DNA? Honestly, who ever imagined such an American world? Think of it not as The Decameron, that fourteenth century tale of 10 people in flight from a pandemic, but the Trumpcameron or perhaps simply Trumpmageddon.

And keep in mind, when assessing this world I’m going to leave behind to those I hold near and dear, that Covid-19 is hardly the worst of it. Behind that pandemic, possibly even linked to it in complex ways, is something so much worse. Yes, the coronavirus and the president’s response to it may seem like the worst of all news as American deaths crest 160,000 with no end in sight, but it isn’t. Not faintly on a planet that’s being heated to the boiling point and whose most powerful country is now run by a crew of pyromaniacs.

It’s hard even to fully conceptualize climate change since it operates on a time scale that’s anything but human. Still, one way to think of it is as a slow-burn planetary version of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And by the way, if you’ll excuse a brief digression, in these years, our president and his men have been intent on ripping up every Cold War nuclear pact in sight, while the tensions between two nuclear-armed powers, the U.S. and China, only intensify and Washington invests staggering sums in “modernizing” its nuclear arsenal. (I mean, how exactly do you “modernize” the already-achieved ability to put an almost instant end to the world as we’ve known it?)

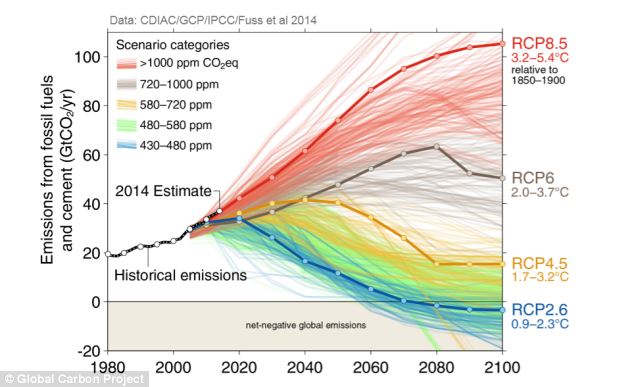

But to return to climate change, remember that 2020 is already threatening to be the warmest year in recorded history, while the five hottest years so far occurred from 2015 to 2019. That should tell you something, no?

The never-ending release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere has been transforming this planet in ways that have now become obvious. My own hometown, New York City, for instance, has officially become part of the humid subtropical climate zone and that’s only a beginning. Everywhere temperatures are rising. They hit 100 degrees this June in, of all places, Siberia. (The Arctic is warming at twice the rate of much of the rest of the planet.) Sea ice is melting fast, while floods and mega-droughts intensify and forests burn in a previously unknown fashion.

And as a recent heat wave across the Middle East — Baghdad hit a record 125 degrees — showed, it’s only going to get hotter. Much hotter and, given how humanity has handled the latest pandemic, how will it handle the chaos that goes with rising sea levels drowning coastlines but also affecting inland populations, ever fiercer storms, and flooding (in recent weeks, the summer monsoon has, for instance, put one third of Bangladesh underwater), not to speak of the migration of refugees from the hardest-hit areas? The answer is likely to be: not well.

And I could go on, but you get the point. This is not the world I either imagined or would ever have dreamed of leaving to those far younger than me. That the men (and they are largely men) who are essentially promoting the pandemicizing and over-heating of this planet will be the greatest criminals in history matters little.

Let’s just hope that, when it comes to creating a better world out of such a god-awful mess, the generations that follow us prove better at it than mine did. If I were a religious man, those would be my prayers.

And here’s my odd hope. As should be obvious from this piece, the recent past, when still the future, was surprisingly unimaginable. There’s no reason to believe that the future — the coming decades — will prove any easier to imagine. No matter the bad news of this moment, who knows what our world might really look like 20 years from now? I only hope, for the sake of my children and grandchildren, that it surprises us all.

Tom Engelhardt is a co-founder of the American Empire Project and the author of a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture. He runs TomDispatch and is a fellow of the Type Media Center. His sixth and latest book is A Nation Unmade by War.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel (the second in the Splinterlands series) Frostlands, Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Copyright 2020 Tom Engelhardt

ooOOoo

This is such a powerful essay written from the heart of a good man.

I, too, wonder and worry about the next twenty years. Indeed, there are the stirrings of a book in my head. How that younger generation are reacting to the present and, more importantly, how they will react and respond to the next few years?

I’m 75 and really hope to live for quite a few more years. Jean is just a few years younger.

But much more importantly I have a son, Alex, who is 49, and a daughter, Maija, who is 48, and a grandson, Morten, of my daughter and her husband, who is 9.

They cannot escape the future!