So far as the Northern Hemisphere is concerned.

Just a very short YouTube video.

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Category: Climate

So far as the Northern Hemisphere is concerned.

Just a very short YouTube video.

Last Monday’s snow, as in the 3rd February, 2025.

oooo

oooo

The first two were taken on our deck, looking East, and the third was taken from my office window looking to the South.

Update as of Wednesday last!

oooo

oooo

oooo

My guess is that we are now experiencing some 8 inches of snow!

Then an update from last Friday afternoon.

Mount Sexton, above and below.

oooo

And I want to return to publishing posts!

My last post was about an accident that I had on the 17th November, last.

Jean is now back home; she came home on Friday, 13th December. However, every day we have a caregiver at home for part of the time. Jean is getting slowly better. I would estimate that at about one percent a day.

I am unsure as to the pattern of my posts. Whether I should go back to scheduling posts three times a week or publish posts on an ad-hoc basis. That will become clearer over the next few weeks.

I am going to start with publishing posts on an ad-hoc basis.

Meanwhile here in Merlin we have had loads of rain.

This is the creek that flows across the lower part of the property.

We live on a profoundly ancient and beautiful planet.

I follow the photographic website Ugly Hedgehog and have been doing for some time. There has been a post recently from the section Photo Gallery and ‘greymule’ from Colorado called his entry ‘A Couple of Desert Scenes’ and I will display just one of his images from that post.

It makes a wonderful connection to today’s post which is from The Conversation.

ooOOoo

Liam Courtney-Davies, University of Colorado Boulder; Christine Siddoway, Colorado College, and Rebecca Flowers, University of Colorado Boulder

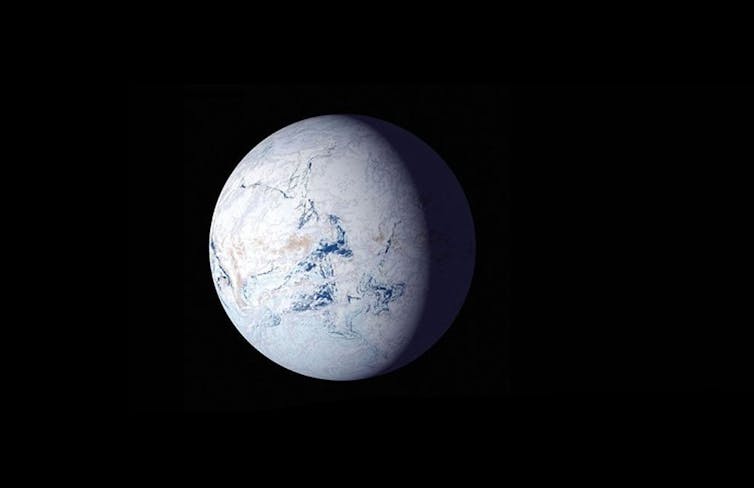

Around 700 million years ago, the Earth cooled so much that scientists believe massive ice sheets encased the entire planet like a giant snowball. This global deep freeze, known as Snowball Earth, endured for tens of millions of years.

Yet, miraculously, early life not only held on, but thrived. When the ice melted and the ground thawed, complex multicellular life emerged, eventually leading to life-forms we recognize today.

The Snowball Earth hypothesis has been largely based on evidence from sedimentary rocks exposed in areas that once were along coastlines and shallow seas, as well as climate modeling. Physical evidence that ice sheets covered the interior of continents in warm equatorial regions had eluded scientists – until now.

In new research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, our team of geologists describes the missing link, found in an unusual pebbly sandstone encapsulated within the granite that forms Colorado’s Pikes Peak.

Pikes Peak, originally named Tavá Kaa-vi by the Ute people, lends its ancestral name, Tava, to these notable rocks. They are composed of solidified sand injectites, which formed in a similar manner to a medical injection when sand-rich fluid was forced into underlying rock.

A possible explanation for what created these enigmatic sandstones is the immense pressure of an overlying Snowball Earth ice sheet forcing sediment mixed with meltwater into weakened rock below.

An obstacle for testing this idea, however, has been the lack of an age for the rocks to reveal when the right geological circumstances existed for sand injection.

We found a way to solve that mystery, using veins of iron found alongside the Tava injectites, near Pikes Peak and elsewhere in Colorado.

Iron minerals contain very low amounts of naturally occurring radioactive elements, including uranium, which slowly decays to the element lead at a known rate. Recent advancements in laser-based radiometric dating allowed us to measure the ratio of uranium to lead isotopes in the iron oxide mineral hematite to reveal how long ago the individual crystals formed.

The iron veins appear to have formed both before and after the sand was injected into the Colorado bedrock: We found veins of hematite and quartz that both cut through Tava dikes and were crosscut by Tava dikes. That allowed us to figure out an age bracket for the sand injectites, which must have formed between 690 million and 660 million years ago.

The time frame means these sandstones formed during the Cryogenian Period, from 720 million to 635 million years ago. The name is derived from “cold birth” in ancient Greek and is synonymous with climate upheaval and disruption of life on our planet – including Snowball Earth.

While the triggers for the extreme cold at that time are debated, prevailing theories involve changes in tectonic plate activity, including the release of particles into the atmosphere that reflected sunlight away from Earth. Eventually, a buildup of carbon dioxide from volcanic outgassing may have warmed the planet again.

University of Exeter professor Timothy Lenton explains why the Earth was able to freeze over.

The Tava found on Pikes Peak would have formed close to the equator within the heart of an ancient continent named Laurentia, which gradually over time and long tectonic cycles moved into its current northerly position in North America today.

The origin of Tava rocks has been debated for over 125 years, but the new technology allowed us to conclusively link them to the Cryogenian Snowball Earth period for the first time.

The scenario we envision for how the sand injection happened looks something like this:

A giant ice sheet with areas of geothermal heating at its base produced meltwater, which mixed with quartz-rich sediment below. The weight of the ice sheet created immense pressures that forced this sandy fluid into bedrock that had already been weakened over millions of years. Similar to fracking for natural gas or oil today, the pressure cracked the rocks and pushed the sandy meltwater in, eventually creating the injectites we see today.

Not only do the new findings further cement the global Snowball Earth hypothesis, but the presence of Tava injectites within weak, fractured rocks once overridden by ice sheets provides clues about other geologic phenomena.

Time gaps in the rock record created through erosion and referred to as unconformities can be seen today across the United States, most famously at the Grand Canyon, where in places, over a billion years of time is missing. Unconformities occur when a sustained period of erosion removes and prevents newer layers of rock from forming, leaving an unconformable contact.

Our results support that a Great Unconformity near Pikes Peak must have been formed prior to Cryogenian Snowball Earth. That’s at odds with hypotheses that attribute the formation of the Great Unconformity to large-scale erosion by Snowball Earth ice sheets themselves.

We hope the secrets of these elusive Cryogenian rocks in Colorado will lead to the discovery of further terrestrial records of Snowball Earth. Such findings can help develop a clearer picture of our planet during climate extremes and the processes that led to the habitable planet we live on today.

Liam Courtney-Davies, Postdoctoral Research Associate in Geological Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder; Christine Siddoway, Professor of Geology, Colorado College, and Rebecca Flowers, Professor of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

All I can add is fascinating.

Once more, an article on the changing climate.

Recently, the BBC News reported that:

Global efforts to tackle climate change are wildly off track, says the UN, as new data shows that warming gases are accumulating faster than at any time in human existence.

Current national plans to limit carbon emissions would barely cut pollution by 2030, the UN analysis shows, leaving efforts to keep warming under 1.5C this century in tatters.

The update comes as a separate report shows that greenhouse gases have risen by over 11% in the last two decades, with atmospheric concentrations surging in 2023.

ooOOoo

Shuang-Ye Wu, University of Dayton

Summer 2024 was officially the Northern Hemisphere’s hottest on record. In the United States, fierce heat waves seemed to hit somewhere almost every day.

Phoenix reached 100 degrees for more than 100 days straight. The 2024 Olympic Games started in the midst of a long-running heat wave in Europe that included the three hottest days on record globally, July 21-23. August was Earth’s hottest month in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s 175-year record.

Overall, the global average temperature was 2.74 degrees Fahrenheit (1.52 degrees Celsius) above the 20th-century average.

That might seem small, but temperature increases associated with human-induced climate change do not manifest as small, even increases everywhere on the planet. Rather, they result in more frequent and severe episodes of heat waves, as the world saw in 2024.

The most severe and persistent heat waves are often associated with an atmospheric pattern called a heat dome. As an atmospheric scientist, I study weather patterns and the changing climate. Here’s how heat domes, the jet stream and climate change influence summer heat waves and the record-hot summer of 2024.

If you listened to weather forecasts during the summer of 2024, you probably heard the term “heat dome” a lot.

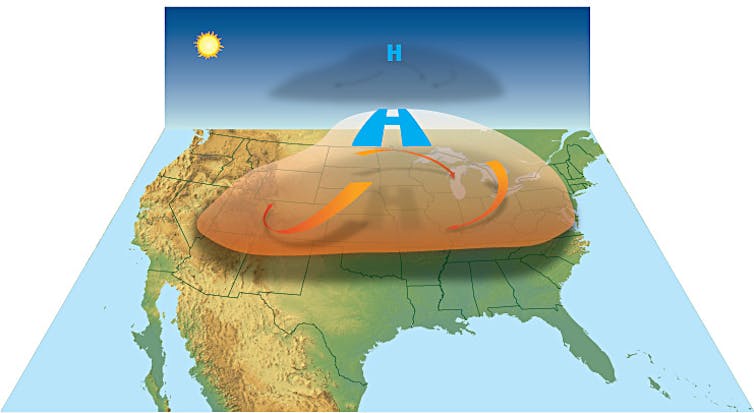

A heat dome is a persistent high-pressure system over a large area. A high-pressure system is created by sinking air. As air sinks, it warms up, decreasing relative humidity and leaving sunny weather. The high pressure also serves as a lid that keeps hot air on the surface from rising and dissipating. The resulting heat dome can persist for days or even weeks.

The longer a heat dome lingers, the more heat will build up, creating sweltering conditions for the people on the ground.

How long these heat domes stick around has a lot to do with the jet stream.

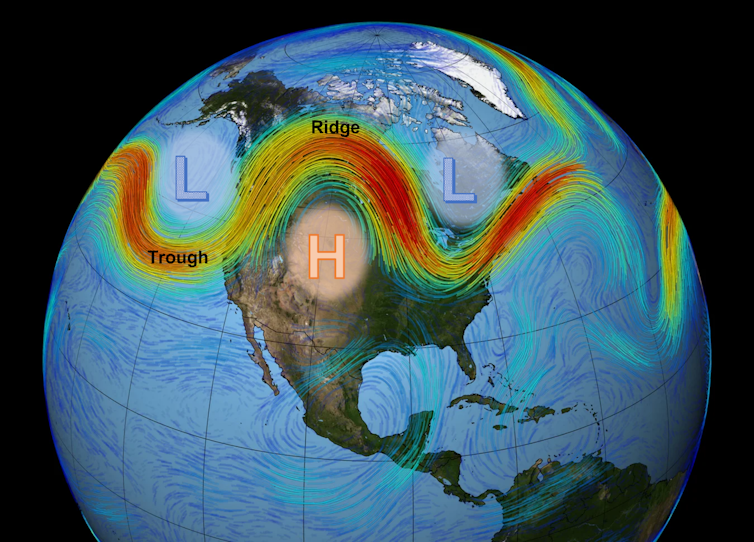

The jet stream is a narrow band of strong winds in the upper atmosphere, about 30,000 feet above sea level. It moves from west to east due to the Earth’s rotation. The strong winds are a result of the sharp temperature difference where the warm tropical air meets the cold polar air from the north in the mid-latitudes.

The jet stream does not flow along a straight path. Rather, it meanders to the north and south in a wavy pattern. These giant meanders are known as the Rossby waves, and they have a major influence on weather.

Where the jet stream arcs northward, forming a ridge, it creates a high-pressure system south of the wave. Where the jet stream dips southward, forming a trough, it creates a low-pressure system north of the jet stream. A low-pressure system contains rising air in the center, which cools and tends to generate precipitation and storms.

Most of our weather is modulated by the position and characteristics of the jet stream.

The jet stream, or any wind, is the result of differences in surface temperature.

In simple terms, warm air rises, creating low pressure, and cold air sinks, creating high pressure. Wind is the movement of the air from high to low pressure. Greater differences in temperature produce stronger winds.

For the Earth as a whole, warm air rises near the equator, and cold air sinks near the poles. The temperature difference between the equator and the pole determines the strength of the jet stream in each hemisphere.

However, that temperature difference has been changing, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere. The Arctic region has been warming about three times faster than the global average. This phenomenon, known as Arctic amplification, is largely caused by the melting of Arctic sea ice, which allows the exposed dark water to absorb more of the Sun’s radiation and heat up faster.

Because the Arctic is warming faster than the tropics, the temperature difference between the two regions is lessened. And that slows the jet stream.

As the jet stream slows, it tends to meander more, causing bigger waves. The bigger waves create larger high-pressure systems. These can often be blocked by the deep low-pressure systems on both sides, causing the high-pressure system to sit over a large area for a long period of time.

Typically, waves in the jet stream pass through the continental United States in around three to five days. When blocking occurs, however, the high-pressure system could stagnate for days to weeks. This allows the heat to build up underneath, leading to blistering heat waves.

Since the jet stream circles around the globe, stagnating waves could occur in multiple places, leading to simultaneous heat waves at the mid-latitude around the world. That happened in 2024, with long-lasting heat waves in Europe, North America, Central Asia and China.

The same meandering behavior of the jet stream also plays a role in extreme winter weather. That includes the southward intrusion of frigid polar air from the polar vortex and conditions for severe winter storms.

Many of these atmospheric changes, driven by human-caused global warming, have significant impacts on people’s health, property and ecosystems around the world.

Shuang-Ye Wu, Professor of Geology and Environmental Geosciences, University of Dayton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

I maybe approaching my own end of life but millions of others are younger than me. When I see a woman with a young baby in her arms I cannot stop myself from wondering what that generation is going to do.

Here is one explanation.

There is no question the world’s weather systems are changing. However, for folk who are not trained in this science it is all a bit mysterious. So thank goodness that The Conversation have not only got a scientist who does know what he is talking about but also they are very happy for it to be republished.

ooOOoo

Zhe Li, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

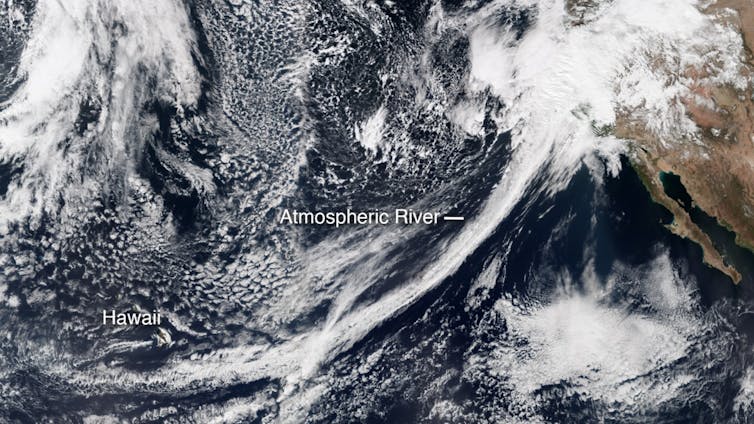

Atmospheric rivers – those long, narrow bands of water vapor in the sky that bring heavy rain and storms to the U.S. West Coast and many other regions – are shifting toward higher latitudes, and that’s changing weather patterns around the world.

The shift is worsening droughts in some regions, intensifying flooding in others, and putting water resources that many communities rely on at risk. When atmospheric rivers reach far northward into the Arctic, they can also melt sea ice, affecting the global climate.

In a new study published in Science Advances, University of California, Santa Barbara, climate scientist Qinghua Ding and I show that atmospheric rivers have shifted about 6 to 10 degrees toward the two poles over the past four decades.

Atmospheric rivers aren’t just a U.S West Coast thing. They form in many parts of the world and provide over half of the mean annual runoff in these regions, including the U.S. Southeast coasts and West Coast, Southeast Asia, New Zealand, northern Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom and south-central Chile.

California relies on atmospheric rivers for up to 50% of its yearly rainfall. A series of winter atmospheric rivers there can bring enough rain and snow to end a drought, as parts of the region saw in 2023.

While atmospheric rivers share a similar origin – moisture supply from the tropics – atmospheric instability of the jet stream allows them to curve poleward in different ways. No two atmospheric rivers are exactly alike.

What particularly interests climate scientists, including us, is the collective behavior of atmospheric rivers. Atmospheric rivers are commonly seen in the extratropics, a region between the latitudes of 30 and 50 degrees in both hemispheres that includes most of the continental U.S., southern Australia and Chile.

Our study shows that atmospheric rivers have been shifting poleward over the past four decades. In both hemispheres, activity has increased along 50 degrees north and 50 degrees south, while it has decreased along 30 degrees north and 30 degrees south since 1979. In North America, that means more atmospheric rivers drenching British Columbia and Alaska.

One main reason for this shift is changes in sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific. Since 2000, waters in the eastern tropical Pacific have had a cooling tendency, which affects atmospheric circulation worldwide. This cooling, often associated with La Niña conditions, pushes atmospheric rivers toward the poles.

The poleward movement of atmospheric rivers can be explained as a chain of interconnected processes.

During La Niña conditions, when sea surface temperatures cool in the eastern tropical Pacific, the Walker circulation – giant loops of air that affect precipitation as they rise and fall over different parts of the tropics – strengthens over the western Pacific. This stronger circulation causes the tropical rainfall belt to expand. The expanded tropical rainfall, combined with changes in atmospheric eddy patterns, results in high-pressure anomalies and wind patterns that steer atmospheric rivers farther poleward.

Conversely, during El Niño conditions, with warmer sea surface temperatures, the mechanism operates in the opposite direction, shifting atmospheric rivers so they don’t travel as far from the equator.

The shifts raise important questions about how climate models predict future changes in atmospheric rivers. Current models might underestimate natural variability, such as changes in the tropical Pacific, which can significantly affect atmospheric rivers. Understanding this connection can help forecasters make better predictions about future rainfall patterns and water availability.

A shift in atmospheric rivers can have big effects on local climates.

In the subtropics, where atmospheric rivers are becoming less common, the result could be longer droughts and less water. Many areas, such as California and southern Brazil, depend on atmospheric rivers for rainfall to fill reservoirs and support farming. Without this moisture, these areas could face more water shortages, putting stress on communities, farms and ecosystems.

In higher latitudes, atmospheric rivers moving poleward could lead to more extreme rainfall, flooding and landslides in places such as the U.S. Pacific Northwest, Europe, and even in polar regions.

In the Arctic, more atmospheric rivers could speed up sea ice melting, adding to global warming and affecting animals that rely on the ice. An earlier study I was involved in found that the trend in summertime atmospheric river activity may contribute 36% of the increasing trend in summer moisture over the entire Arctic since 1979.

So far, the shifts we have seen still mainly reflect changes due to natural processes, but human-induced global warming also plays a role. Global warming is expected to increase the overall frequency and intensity of atmospheric rivers because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture.

How that might change as the planet continues to warm is less clear. Predicting future changes remains uncertain due largely to the difficulty in predicting the natural swings between El Niño and La Niña, which play an important role in atmospheric river shifts.

As the world gets warmer, atmospheric rivers – and the critical rains they bring – will keep changing course. We need to understand and adapt to these changes so communities can keep thriving in a changing climate.

Zhe Li, Postdoctoral Researcher in Earth System Science, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

Those last two paragraphs of the above article show the difficulty in coming up with clear predictions of the future. As was said: ‘How that might change as the planet continues to warm is less clear. Predicting future changes remains uncertain due largely to the difficulty in predicting the natural swings between El Niño and La Niña, which play an important role in atmospheric river shifts.‘

This attracted me very much, and I wanted to share it with you.

The opening paragraph of this article caught my eye so I read it fully. As it was published in The Conversation then that meant I could republish it.

ooOOoo

James L. Fitzsimmons, Middlebury

The ancient Maya believed that everything in the universe, from the natural world to everyday experiences, was part of a single, powerful spiritual force. They were not polytheists who worshipped distinct gods but pantheists who believed that various gods were just manifestations of that force.

Some of the best evidence for this comes from the behavior of two of the most powerful beings of the Maya world: The first is a creator god whose name is still spoken by millions of people every fall – Huracán, or “Hurricane.” The second is a god of lightning, K’awiil, from the early first millennium C.E.

As a scholar of the Indigenous religions of the Americas, I recognize that these beings, though separated by over 1,000 years, are related and can teach us something about our relationship to the natural world.

Huracán was once a god of the K’iche’, one of the Maya peoples who today live in the southern highlands of Guatemala. He was one of the main characters of the Popol Vuh, a religious text from the 16th century. His name probably originated in the Caribbean, where other cultures used it to describe the destructive power of storms.

The K’iche’ associated Huracán, which means “one leg” in the K’iche’ language, with weather. He was also their primary god of creation and was responsible for all life on earth, including humans.

Because of this, he was sometimes known as U K’ux K’aj, or “Heart of Sky.” In the K’iche’ language, k’ux was not only the heart but also the spark of life, the source of all thought and imagination.

Yet, Huracán was not perfect. He made mistakes and occasionally destroyed his creations. He was also a jealous god who damaged humans so they would not be his equal. In one such episode, he is believed to have clouded their vision, thus preventing them from being able to see the universe as he saw it.

Huracán was one being who existed as three distinct persons: Thunderbolt Huracán, Youngest Thunderbolt and Sudden Thunderbolt. Each of them embodied different types of lightning, ranging from enormous bolts to small or sudden flashes of light.

Despite the fact that he was a god of lightning, there were no strict boundaries between his powers and the powers of other gods. Any of them might wield lightning, or create humanity, or destroy the Earth.

The Popol Vuh implies that gods could mix and match their powers at will, but other religious texts are more explicit. One thousand years before the Popol Vuh was written, there was a different version of Huracán called K’awiil. During the first millennium, people from southern Mexico to western Honduras venerated him as a god of agriculture, lightning and royalty.

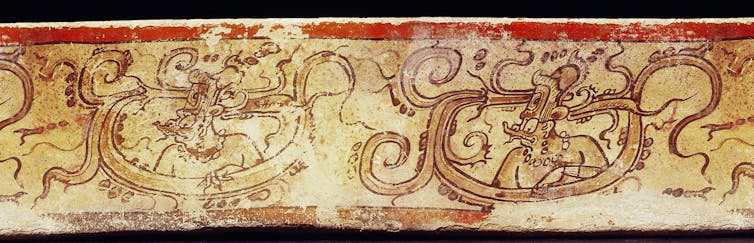

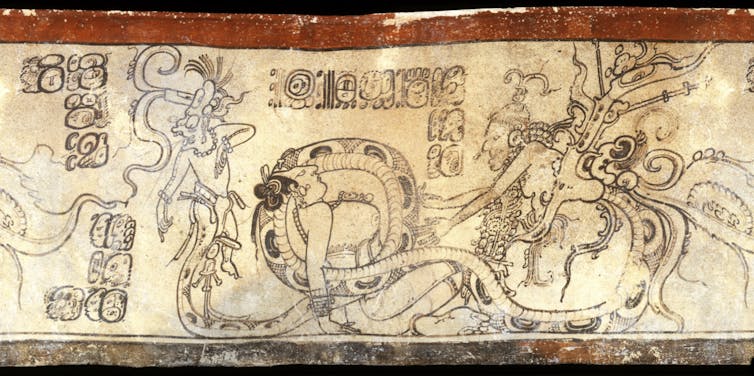

Illustrations of K’awiil can be found everywhere on Maya pottery and sculpture. He is almost human in many depictions: He has two arms, two legs and a head. But his forehead is the spark of life – and so it usually has something that produces sparks sticking out of it, such as a flint ax or a flaming torch. And one of his legs does not end in a foot. In its place is a snake with an open mouth, from which another being often emerges.

Indeed, rulers, and even gods, once performed ceremonies to K’awiil in order to try and summon other supernatural beings. As personified lightning, he was believed to create portals to other worlds, through which ancestors and gods might travel.

For the ancient Maya, lightning was raw power. It was basic to all creation and destruction. Because of this, the ancient Maya carved and painted many images of K’awiil. Scribes wrote about him as a kind of energy – as a god with “many faces,” or even as part of a triad similar to Huracán.

He was everywhere in ancient Maya art. But he was also never the focus. As raw power, he was used by others to achieve their ends.

Rain gods, for example, wielded him like an ax, creating sparks in seeds for agriculture. Conjurers summoned him, but mostly because they believed he could help them communicate with other creatures from other worlds. Rulers even carried scepters fashioned in his image during dances and processions.

Moreover, Maya artists always had K’awiil doing something or being used to make something happen. They believed that power was something you did, not something you had. Like a bolt of lightning, power was always shifting, always in motion.

Because of this, the ancient Maya thought that reality was not static but ever-changing. There were no strict boundaries between space and time, the forces of nature or the animate and inanimate worlds.

Everything was malleable and interdependent. Theoretically, anything could become anything else – and everything was potentially a living being. Rulers could ritually turn themselves into gods. Sculptures could be hacked to death. Even natural features such as mountains were believed to be alive.

These ideas – common in pantheist societies – persist today in some communities in the Americas.

They were once mainstream, however, and were a part of K’iche’ religion 1,000 years later, in the time of Huracán. One of the lessons of the Popol Vuh, told during the episode where Huracán clouds human vision, is that the human perception of reality is an illusion.

The illusion is not that different things exist. Rather it is that they exist independent from one another. Huracán, in this sense, damaged himself by damaging his creations.

Hurricane season every year should remind us that human beings are not independent from nature but part of it. And like Hurácan, when we damage nature, we damage ourselves.

James L. Fitzsimmons, Professor of Anthropology, Middlebury

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

It is such a powerful message, that when we damage nature, we damage ourselves.

But I am unaware, no we are both unaware of a solution, and there doesn’t appear to be a government desire to make this the number one topic.

Please, if there is anyone who reads this post and has a more positive message then we would be very keen to hear from you.

We are speaking of the universe.

I follow Patrice Ayme and have done for many years. Some of his posts are super-intellectual and those I struggle to understand.

But a post published on September 8th, 2024 was very easy for me, and countless others no doubt, to understand and I have pleasure in republishing it on Learning from Dogs today.

ooOOoo

September 8, 2024

I doubt that there are civilizations around. We are facing a galaxy devoid of intelligent aliens: little green mats out there, not little green men.

First, we don’t see them. With foreseeable technology (hibernation, nuclear propulsion, compact thermonuclear reactors, bioengineering, AI, quantum computers) we should be able to send very large interstellar spaceships at 1,000 kilometers per second… Thus it would take a millennium to colonize the Centaur tri-star system…. 25,000 years to colonize a 200 light years across ball… And the entire galaxy in ten million years… Wars would only accelerate the expansion. So if there was a galactic civilization, within ten million years it would have spanned the entire galaxy and its presence should be in sight.

Second, life took nearly four billion years to evolve animals. Bacterial life could have been nearly extinguished on Earth many times…. Be it only during the Snowball Earths episodes. A star whizzing by could have launched a thousand large comets. The large planets could have fallen inward.

Third, ultra intelligent life may not be able to have hands or tentacles and thus develop industry. Once intelligent life forms have evolved, say sea lions or parrots, let alone wolves, they may just be sitting ducks for the next disaster which would revert life to the bacterial level, erasing billions of years of evolution.

Fourth, when civilization is launched, it can fail… And not get a second chance (from lack of availability of mines after easy picking during the initial civilization).

Fifth, nuclear powered Earth is special. Earth has plate tectonics, probably from a nuclear reactor at the core, keeps the CO2 just so for a temperate temperature… Water, but not too much. Her large Moon stabilizes her. Earth doesn’t have a weird rotation like Venus (retrograde and slow) or Mars (spectacularly tilting axis). Ian Miller has aluminosilicates considerations on top of that.

So I don’t expect little green men… Besides those sent by the perverse Putin…

Just when we thought we knew of all the stress, here is another one: if we go extinct, the universe loses its soul! We have thus found a new Superior Moral Directive: SUS, Save Unique Soul!

Expect little green mats, not little green men.

Patrice Ayme

ooOOoo

A couple of weeks ago I gave a talk to our local Freethinkers group and called it The Next Ten Years. It began, thus:

This presentation is about the world of the future; of the near future. And the biggest issue, most agree, is the change in the climate.

The Global Temperature anomaly, as of last year, 2023, is 1.17 Centigrade, 2.11 Fahrenheit, above the long-term average from 1951 to 1980. The 10 most recent years are the warmest years on record.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry is quoted as saying that ‘a goal without a plan is just a wish.’ So my plan is to show you how we can change, no let me put that more strongly, how we must change in the next ten years. Because our present habits are ruining the world.