A wonderful postscript to my letter to Mr. Neptune!

The following was published last Wednesday and appeared on The Conversation site.

I found it very interesting and wanted to share it with you.

ooOOoo

Scientists have been drilling into the ocean floor for 50 years – here’s what they’ve found so far

September 26, 2018

By Professor Suzanne O’Connell, Professor of Earth & Environmental Sciences, Wesleyan University

It’s stunning but true that we know more about the surface of the moon than about the Earth’s ocean floor. Much of what we do know has come from scientific ocean drilling – the systematic collection of core samples from the deep seabed. This revolutionary process began 50 years ago, when the drilling vessel Glomar Challenger sailed into the Gulf of Mexico on August 11, 1968 on the first expedition of the federally funded Deep Sea Drilling Project.

I went on my first scientific ocean drilling expedition in 1980, and since then have participated in six more expeditions to locations including the far North Atlantic and Antaractica’s Weddell Sea. In my lab, my students and I work with core samples from these expeditions. Each of these cores, which are cylinders 31 feet long and 3 inches wide, is like a book whose information is waiting to be translated into words. Holding a newly opened core, filled with rocks and sediment from the Earth’s ocean floor, is like opening a rare treasure chest that records the passage of time in Earth’s history.

Over a half-century, scientific ocean drilling has proved the theory of plate tectonics, created the field of paleoceanography and redefined how we view life on Earth by revealing an enormous variety and volume of life in the deep marine biosphere. And much more remains to be learned.

Technological innovations

Two key innovations made it possible for research ships to take core samples from precise locations in the deep oceans. The first, known as dynamic positioning, enables a 471-foot ship to stay fixed in place while drilling and recovering cores, one on top of the next, often in over 12,000 feet of water.

Anchoring isn’t feasible at these depths. Instead, technicians drop a torpedo-shaped instrument called a transponder over the side. A device called a transducer, mounted on the ship’s hull, sends an acoustic signal to the transponder, which replies. Computers on board calculate the distance and angle of this communication. Thrusters on the ship’s hull maneuver the vessel to stay in exactly the same location, countering the forces of currents, wind and waves.

Another challenge arises when drill bits have to be replaced mid-operation. The ocean’s crust is

composed of igneous rock that wears bits down long before the desired depth is reached.

When this happens, the drill crew brings the entire drill pipe to the surface, mounts a new drill bit and returns to the same hole. This requires guiding the pipe into a funnel shaped re-entry cone, less than 15 feet wide, placed in the bottom of the ocean at the mouth of the drilling hole. The process, which was first accomplished in 1970, is like lowering a long strand of spaghetti into a quarter-inch-wide funnel at the deep end of an Olympic swimming pool.

Confirming plate tectonics

When scientific ocean drilling began in 1968, the theory of plate tectonics was a subject of active debate. One key idea was that new ocean crust was created at ridges in the seafloor, where oceanic plates moved away from each other and magma from earth’s interior welled up between them. According to this theory, crust should be new material at the crest of ocean ridges, and its age should increase with distance from the crest.

The only way to prove this was by analyzing sediment and rock cores. In the winter of 1968-1969, the Glomar Challenger drilled seven sites in the South Atlantic Ocean to the east and west of the Mid-Atlantic ridge. Both the igneous rocks of the ocean floor and overlying sediments aged in perfect agreement with the predictions, confirming that ocean crust was forming at the ridges and plate tectonics was correct.

Reconstructing earth’s history

The ocean record of Earth’s history is more continuous than geologic formations on land, where erosion and redeposition by wind, water and ice can disrupt the record. In most ocean locations sediment is laid down particle by particle, microfossil by microfossil, and remains in place, eventually succumbing to pressure and turning into rock.

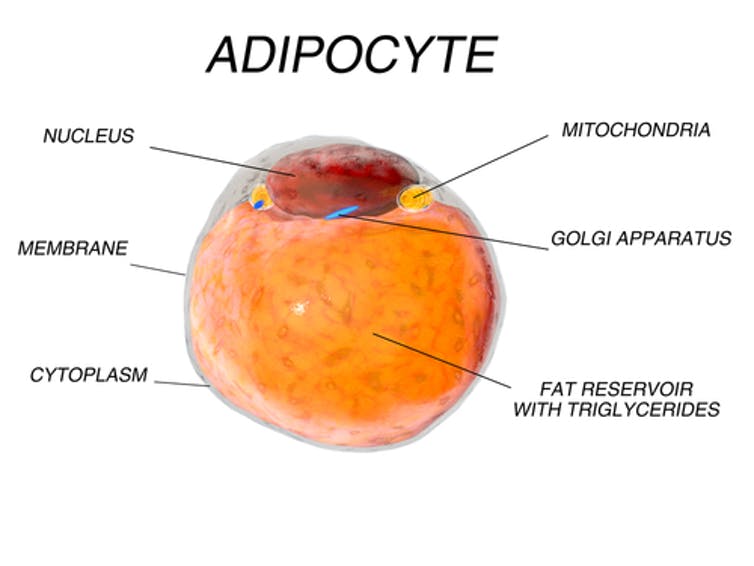

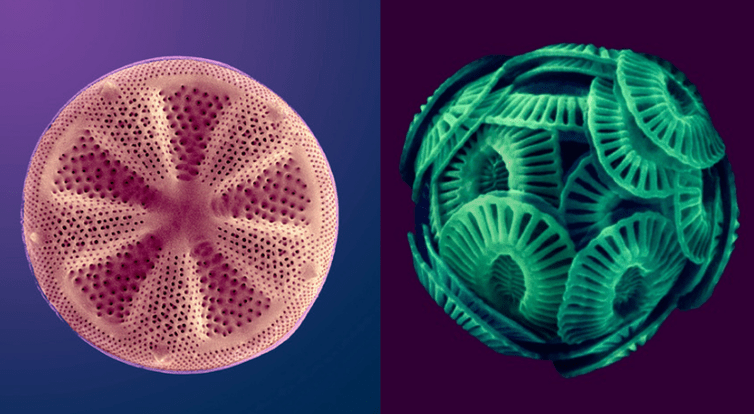

Microfossils (plankton) preserved in sediment are beautiful and informative, even though some

are smaller than the width of a human hair. Like larger plant and animal fossils, scientists can use these delicate structures of calcium and silicon to reconstruct past environments.

Thanks to scientific ocean drilling, we know that after an asteroid strike killed all non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago, new life colonized the crater rim within years, and within 30,000 years a full ecosystem was thriving. A few deep ocean organisms lived right through the meteorite impact.

Ocean drilling has also shown that ten million years later, a massive discharge of carbon – probably from extensive volcanic activity and methane released from melting methane hydrates – caused an abrupt, intense warming event, or hyperthermal, called the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. During this episode, even the Arctic reached over 73 degrees Fahrenheit.

The resulting acidification of the ocean from the release of carbon into the atmosphere and ocean caused massive dissolution and change in the deep ocean ecosystem.

This episode is an impressive example of the impact of rapid climate warming. The total amount of carbon released during the PETM is estimated to be about equal to the amount that humans will release if we burn all of Earth’s fossil fuel reserves. Yet, an important difference is that the carbon released by the volcanoes and hydrates was at a much slower rate than we are currently releasing fossil fuel. Thus we can expect even more dramatic climate and ecosystem changes unless we stop emitting carbon.

Finding life in ocean sediments

Scientific ocean drilling has also shown that there are roughly as many cells in marine sediment as in the ocean or in soil. Expeditions have found life in sediments at depths over 8000 feet; in seabed deposits that are 86 million years old; and at temperatures above 140 degrees Fahrenheit.

Today scientists from 23 nations are proposing and conducting research through the International Ocean Discovery Program, which uses scientific ocean drilling to recover data from seafloor sediments and rocks and to monitor environments under the ocean floor. Coring is producing new information about plate tectonics, such as the complexities of ocean crust formation, and the diversity of life in the deep oceans.

This research is expensive, and technologically and intellectually intense. But only by exploring the deep sea can we recover the treasures it holds and better understand its beauty and complexity.

ooOOoo

Did the phrase in the first paragraph of the article jump out for you as it did for me?

This one: “…we know more about the surface of the moon than about the Earth’s ocean floor.”

Doesn’t Mr. Neptune hold his cards close to his chest.

Wonder if he communes with man’s best friend??