Doing nothing is not an option.

Introduction

So back to non-doggy stuff although I hope the themes of truth and integrity continue to rein supreme though this blog!

In the last couple of weeks, I have devoted a number of posts to the subject of change, as in how do we humans change. The first post was Changing the person: Me where I started examining the process of change; by process I mean the models of change commonly understood in, say, management change.

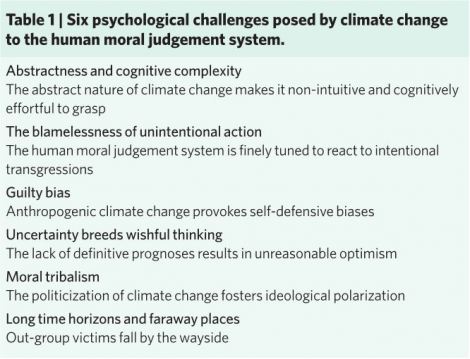

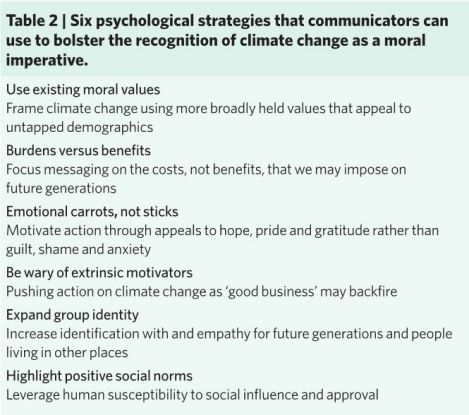

The next post was You have to feel it! which drew heavily on research from Ezra M. Markowitz & Azim F. Shariff regarding the psychological aspects posed by climate change to the human moral judgement system.

The final post was From feeling to doing. In this post, David Roberts of Grist showed that one could put aside all the ‘head stuff’ about change and in just 15 minutes cover all that one would ever want to know about the biggest issue of all facing this planet.

So rather a long introduction to two guest posts that today and tomorrow set out the case for what we all have to consider; doing nothing is just not a viable option. The first is from Martin Lack of the popular and hard-hitting blog Lack of Environment.

oooOOOooo

Avoiding the catastrophe of indifference.

by Martin Lack.

Paul has very kindly invited me to follow-up his recent post regarding David Roberts’ item on the Grist blog entitled ‘Why climate change doesn’t spark moral outrage, and how it could’ followed by a second post in which was embedded David Roberts’ excellent video ‘Climate change is simple – we do something or we’re screwed’.

So my guest post is an expansion of a comment I submitted in response to the first of those two posts, You have to feel it. However it would be wrong not to first add my voice to all those that have applauded David Roberts for all his excellent work.

In 2010, the Australian social anthropologist Clive Hamilton published Requiem for a Species: Why we Resist the Truth About Climate Change – one of the scariest but most important books I think I have ever read.

Reading Hamilton’s book was one of the reasons I decided, as part of my MA in Environmental Politics, to base my dissertation on climate change scepticism in the UK.

In the process, I read much but Hamilton’s book was one of very few that I actually read from cover to cover – I simply did not have time to read fully all the books for my research. However, because I have a background in geology and hydrogeology, my greatest challenge was learning to think like a social scientist.

I was all for taking these climate change sceptics head on and demolishing their pseudo-scientific arguments or taking them to task for the ideological prejudices that drive them to reject what scientists tell us. Thus, it fell to my dissertation supervisor to mention politely but firmly that I needed to disengage with the issues and analyse patterns of behaviour and frequency of arguments favoured by different groups of people. In short, I needed to stop trying to prove the scientific consensus correct and start understanding the views held by those that dispute that consensus.

Having said how I read Professor Hamilton’s book in full, I must admit to learning about a load of other equally-scary sounding books since subscribing to Learning from Dogs; Lester Brown’s World on the Edge: How to Prevent Environmental and Economic Collapse being just one that comes to mind!

Then of course there is what David Roberts himself says, which is just as scary. I think we have good reason to be scared. However, as Hamilton points out, we must move beyond being scared, which is simply debilitating, and channel our frustration into positive action.

Because if we do not, there is a great deal of circumstantial evidence to suggest that civilisation may well fail. If that means engaging in acts of civil disobedience, as it has done for James Hansen and many others, well, so be it. I suspect that nothing worthwhile has ever been achieved without someone breaking the law in order to draw attention to injustice – the abolition of slavery and child labour, the extension for all of the right to vote including women, come to mind.

That is the conclusion of Hamilton’s book; that civil disobedience is almost inevitable (p.225). Just as turkeys won’t vote for Christmas, our politicians are not going to vote for climate change mitigation unless we demand that they do so.

So it was the steer from my dissertation supervisor that lead me to read David Aaronovitch’s Voodoo Histories: How Conspiracy Theory Has Shaped Modern History, and much more about psychology. All of which guided the Introductory section of my dissertation, which summarised the philosophical roots of scepticism, the political misuse of scepticism, and the psychology of denial; see a recent post on my blog Lack of Environment. In terms of what I want to say here, it is an elaboration of the last of those topics, the psychology of denial. Indeed, it formed the preamble to the findings of my research.

To help me research this unfamiliar subject, my dissertation supervisor sent me a PDF copy of a paper written by Janis L. Dickinson in 2009 and published in Ecology and Society. It was called ‘The People Paradox: Self-Esteem Striving, Immortality Ideologies, and Human Response to Climate Change’ and dealt with a challenging, almost taboo subject, namely our own mortality.

Despite my initial reluctance to learn about psychology, the more I read the more I realised just how central psychology was to explaining why we humans have failed to address the problem of climate change.

I ended up summarising the work of Dickinson, together with other sources of material, in the following manner.

In considering reasons for the collective human failure to act to prevent anthropogenic global warming (AGW), a number of authors appear to have been influenced by Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death (1973). For example, Aaronovitch proposed that we try to avoid the “catastrophe of indifference” that a world devoid of meaning or purpose represents (p. 340). Hamilton suggested that climate disruption “has the smell of death about it” (p. 215).

Janis Dickinson elaborates a little more, exploring what she describes as “…one of the key psychological links between the reality of global climate change and the difficulty of mobilizing individuals and groups to confront the problem in a rational and timely manner”, then referring to what psychologists call terror management theory (TMT) – Dickinson also categorises denial of climate change; denial of human responsibility and immediacy of the problem as proximal responses (Dickinson 2009).

Furthermore, as referenced here, both Dickinson and Hamilton suggest that other distal TMT responses, such as focussing on maintaining self-esteem or enhancing self-gratification, can be counter-intuitive and counter-productive. Dickinson summarises the recent work of Tim Dyson by saying “[b]ehavioral response to the threat of global climate change simply does not match its unique potential for cumulative, adverse, and potentially chaotic outcomes” (ibid).

Based on the evidence of the most frequently used arguments for dismissing the scientific consensus regarding climate change, I collated the findings of my research and which might be summarised as follows:

Having analysed the output of such UK-based Conservative think-tanks (CTTs), along with that of scientists, economists, journalists, politicians and others, it would appear that the majority of CTTs dispute the existence of a legitimate consensus, whereas the majority of sceptical journalists focus on conspiracy theories; the majority of scientists and economists equate environmentalism with a new religion; and politicians and others analysed appear equally likely to cite denialist or economic arguments for inaction.

As I find myself saying quite frequently, the most persistent arguments against taking action to mitigate climate change are the economic ones.

However, as all the authors mentioned have suggested, or at least inferred, I think it is undoubtedly true that the most potent obstacle to people facing up to the truth of climate change is our psychological reluctance to accept responsibility for something that is obviously deteriorating – namely our environment!

Nevertheless, all is not yet lost. We do not all need to go back to living in the Dark Ages to prevent societal and environmental collapse but we do need to accept a couple of fundamental realities:

- Burning fossilised carbon is trashing the planet. Therefore, fossil fuel use must be substituted in every possible process as rapidly as possible. Unfortunately, it is not substitutable in the most damaging process of all; aviation. That merely increases the urgency of substituting where we can (i.e. power, lighting and temperature control).

- Poor people in developing countries have a legitimate right to aspire to having a more comfortable life but the planet definitely cannot cope with 7 to 10 billion people living like we do in the “developed” countries.

Once we accept these realities, we will learn to use less fossil fuels and, if we can become self-sufficient using renewable energy sources, we can have a flat-screen TV in every room and leave them on standby and the A/C on full power 24/7 and still have a clear conscience. However, we must get off fossil fuels ASAP.

oooOOOooo

I am indebted to Martin for writing such an insightful analysis of how we all have to change. Tomorrow, another guest post further exploring the options that face us all as we work towards a sustainable future. As I opened this post, doing nothing is not an option!