A copy of a Picture Parade from a year ago!

(And I’m getting on with the book!)

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

As I said a year ago, this has nothing to do with dogs but I sense there won’t be any complaint!

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Category: Science

A copy of a Picture Parade from a year ago!

(And I’m getting on with the book!)

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

As I said a year ago, this has nothing to do with dogs but I sense there won’t be any complaint!

There’s no shortage of good news about the benefits of a dog in your life.

I have been reading recently about how having a dog, or six, in your life is linked to that life being extended. As I shall be 75 in eleven days time this was not a casual thought.

The reading was as a result of two new studies being published recently: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. I was going to ‘top and tail’ one of these articles and publish it in this place.

But then I decided to do my own research and first off went to the American Heart Association website.

I was blown away by the results. Using their own search facility I put in the word ‘dog’ and received 313 responses. Top of the list were the two articles that I just mentioned.

But first a word about the Association. As their History page very comprehensively says (just a small extract from me):

Before the American Heart Association existed, people with heart disease were thought to be doomed to complete bed rest — or destined to imminent death.

But a handful of pioneering physicians and social workers believed it didn’t have to be that way. They conducted studies to learn more about heart disease, America’s No. 1 killer. Then, on June 10, 1924, they met in Chicago to form the American Heart Association — believing that scientific research could lead the way to better treatment, prevention and ultimately a cure. The early American Heart Association enlisted help from hundreds, then thousands, of physicians and scientists.

“We were living in a time of almost unbelievable ignorance about heart disease,” said Paul Dudley White, one of six cardiologists who founded the organization.

In 1948, the association reorganized, transforming from a professional scientific society to a nationwide voluntary health organization composed of science and lay volunteers and supported by professional staff.

Since then, the AHA has grown rapidly in size and influence — nationally and internationally — into an organization of more than 33 million volunteers and supporters dedicated to improving heart health and reducing deaths from cardiovascular diseases and stroke.

Here is a timeline of American Heart Association milestones in more than 90 years of lifesaving history:

Read more if you want to here.

Now I’m going to republish the first two articles from that long list of published items. The first is Do dog owners live longer?

ooOOoo

As dog lovers have long suspected, owning a canine companion can be good for you. In fact, two recent studies and analyses published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, a scientific journal of the American Heart Association, suggest your four-legged friend may help you do better after a heart attack or stroke and may help you live a longer, healthier life. And that’s great news for dog parents!

Dog owners have better results after a major health event.

The studies found that, overall, dog owners tend to live longer than non-owners. And they often recover better from major health events such as heart attack or stroke, especially if they live alone.

Some exciting stats for dog owners:

Learn more about what the research shows.

Move more, stress less.

Interacting with dogs can boost your production of “happy hormones” such as oxytocin, serotonin and dopamine. This can lead to a greater sense of well-being and help lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol. And having a dog can help lower blood pressure and cholesterol, ease depression and improve fitness.

Studies show that people who walk their dogs get significantly more exercise than those who don’t. And there’s a bonus: our pets can also help us feel less social anxiety and interact more with other humans. Maybe that’s why dog owners report less loneliness, depression and social isolation.

Make the most of dog ownership.

Here are some tips to make the most of your four-legged companion time:

\Source:

Dog ownership associated with longer life, especially among heart attack and stroke survivors, Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes Journal Report, October 2019

ooOOoo

The second is also very recent, about the findings from Sweden.

ooOOoo

By American Heart Association News

Letting your health go to the dogs might turn out to be a great idea: New research bolsters the association between dog ownership and longer life, especially for people who have had heart attacks or strokes.

Earlier studies have shown dog ownership alleviates social isolation, improves physical activity and lowers blood pressure. The new work builds on that, said Dr. Glenn N. Levine, who led a committee that wrote a 2013 report about pet ownership for the American Heart Association.

“While these non-randomized studies cannot prove that adopting or owning a dog directly leads to reduced mortality, these robust findings are certainly at least suggestive of this,” he said in a news release.

The two new studies were published Tuesday in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

One study, from Sweden, compared dog owners and non-owners after a heart attack or stroke. Records of nearly 182,000 people who’d had heart attacks and nearly 155,000 people who’d had strokes were examined. Dog ownership was confirmed with data from the Swedish Board of Agriculture, where registration of dog ownership has been mandatory since 2001, and the Swedish Kennel Club, where pedigree dogs have been registered since 1889.

When compared with people who didn’t own dogs, owners who lived alone had a 33% lower risk of dying after being hospitalized for a heart attack. For dog owners who lived with a partner or child, the risk was 15% lower.

Dog-owning stroke survivors saw a similar benefit. The risk of death after hospitalization for those who lived alone was 27% lower. It was 12% lower if they lived with a partner or child.

What’s behind the canine advantage?

“We know that social isolation is a strong risk factor for worse health outcomes and premature death,” said study co-author Dr. Tove Fall, a doctor of veterinary medicine and a professor at Uppsala University in Sweden. “Previous studies have indicated that dog owners experience less social isolation and have more interaction with other people. Furthermore, keeping a dog is a good motivation for physical activity, which is an important factor in rehabilitation and mental health.”

The second set of researchers reviewed patient data from more than 3.8 million people in 10 separate studies.

Compared to non-owners, dog owners had a 24% reduced risk of dying from any cause; a 31% reduced risk of dying from cardiovascular-related issues; and a 65% reduced risk dying after a heart attack.

The study did not account for factors such as better fitness or an overall healthier lifestyle that could be associated with dog ownership, said co-author Dr. Caroline Kramer, an endocrinologist and clinician scientist at Leadership Sinai Centre for Diabetes at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto. “The results, however, were very positive.”

As a dog owner herself, Kramer said adopting her miniature Schnauzer, Romeo, “increased my steps and physical activity each day, and he has filled my daily routine with joy and unconditional love.”

Tove, however, cautioned more research needs to be done before people are prescribed dogs for health reasons. “Moreover, from an animal welfare perspective, dogs should only be acquired by people who feel they have the capacity and knowledge to give the pet a good life.”

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email editor@heart.org.

American Heart Association News Stories

American Heart Association News covers heart disease, stroke and related health issues. Not all views expressed in American Heart Association News stories reflect the official position of the American Heart Association.

Copyright is owned or held by the American Heart Association, Inc., and all rights are reserved. Permission is granted, at no cost and without need for further request, to link to, quote, excerpt or reprint from these stories in any medium as long as no text is altered and proper attribution is made to the American Heart Association News. See full terms of use.

HEALTH CARE DISCLAIMER: This site and its services do not constitute the practice of medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always talk to your health care provider for diagnosis and treatment, including your specific medical needs. If you have or suspect that you have a medical problem or condition, please contact a qualified health care professional immediately. If you are in the United States and experiencing a medical emergency, call 911 or call for emergency medical help immediately.

ooOOoo

Case made; hook, line and sinker!

A very interesting development.

I was chatting to my very old friend, as in the number of years, Richard Maugham yesterday and shortly after the call he sent me an email with a link to a recent item on the BBC News website.

Most of you regulars know that Jeannie was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (PD) in December, 2015 and coincidentally at the same time Richard was also diagnosed with PD.

I’m sure there are a few who read this blog that either have PD of know or someone who has it.

ooOOoo

By Michelle Roberts,

Health editor, BBC News online

17th September, 2019

A drug used to treat enlarged prostates may be a powerful medicine against Parkinson’s disease, according to an international team of scientists.

Terazosin helps ease benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) by relaxing the muscles of the bladder and prostate.

But researchers believe it has another beneficial action, on brain cells damaged by Parkinson’s.

They say the drug might slow Parkinson’s progression – something that is not possible currently.

Cell death

They studied thousands of patients with both BPH and Parkinson’s.

Their findings, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, suggest the alpha-blocker drug protects brain cells from destruction.

Parkinson’s is a progressive condition affecting the brain, for which there is currently no cure.

Existing Parkinson’s treatments can help with some of the symptoms but can’t slow or reverse the loss of neurons that occurs with the disease.

Terazosin may help by activating an enzyme called PGK1 to prevent this brain cell death, the researchers, from the University of Iowa, in the US and the Beijing Institute for Brain Disorders, China, say.

Clinical trials

When they tested the drug in rodents it appeared to slow or stop the loss of nerve cells.

To begin assessing if the drug might have the same effect in people, they searched the medical records of millions of US patients to identify men with BPH and Parkinson’s.

They studied 2,880 Parkinson’s patients taking terazosin or similar drugs that target PGK1 and a comparison group of 15,409 Parkinson’s patients taking a different treatment for BPH that had no action on PGK1.

Patients on the drugs targeting PGK1 appeared to fare better in terms of Parkinson’s disease symptoms and progression, which the researchers say warrants more study in clinical trials, which they plan to begin this year.

‘Exciting area’

Lead researcher Dr Michael Welsh says while it is premature to talk about a cure, the findings have the potential to change the lives of people with Parkinson’s.

“Today, we have zero treatments that change the progressive course of this neurodegenerative disease,” she says.

“That’s a terrible state, because as our population ages Parkinson’s disease is going to become increasingly common.

“So, this is really an exciting area of research.”

‘Disease modifying’

Given that terazosin has a proven track record for treating BPH, he says, getting it approved and “repurposed” as a Parkinson’s drug should be achievable if the clinical trials go well.

The trials, which will take a few years, will compare the drug with a placebo to make sure it is safe and effective in Parkinson’s.

Co-researcher Dr Nandakumar Narayanan, who treats patients with Parkinson’s disease said: “We need these randomised controlled trials to prove that these drugs really are disease modifying.

“If they are, that would be a great thing.”

Prof David Dexter from Parkinson’s UK said: “These exciting results show that terazosin may have hidden potential for slowing the progression of Parkinson’s, something that is desperately needed to help people live well for longer.

“While it is early days, both animal models and studies looking at people who already take the drug show promising signs that need to be investigated further.”

ooOOoo

I have now written to the Journal of Clinical Investigation, (JCI).

Interestingly, if one goes to the website of the JCI then one reads the following on the ‘About’ page:

The Journal of Clinical Investigation is a premier venue for discoveries in basic and clinical biomedical science that will advance the practice of medicine.

The JCI was founded in 1924 and is published by the ASCI, a nonprofit honor organization of physician-scientists incorporated in 1908. See the JCI’s Wikipedia entry for detailed information.

- Impact Factor: 12.282 (2018). The JCI is one of the top journals in the “Medicine, Research & Experimental” category.

- Broad readership and scope. The JCI reaches readers across a wide range of medical disciplines and sectors. The journal publishes basic and phase I/II clinical research submissions in all biomedical specialties, including Autoimmunity, Gastroenterology, Immunology, Metabolism, Nephrology, Neuroscience, Oncology, Pulmonology, Vascular Biology, and many others.

- Open access. All research is available to the public for free. The JCI deposits published research articles in PubMed Central, which satisfies the NIH Public Access Policy and other similar funding agency requirements.

It’s a small step forward!

A short but interesting YouTube video.

I’m going to try and publish some posts on a whole range of topics. The one common denominator is that they are of interest to yours truly. Hopefully I am not alone in this!

It’s going to be a bit ad hoc including responding to comments from a week today until October 8th/9th.

But today’s post is a short video that nonetheless makes for fascinating viewing.

Onwards and upwards!

More dog food contaminated with Salmonella.

There’s a continuing problem with Salmonella.

ooOOoo

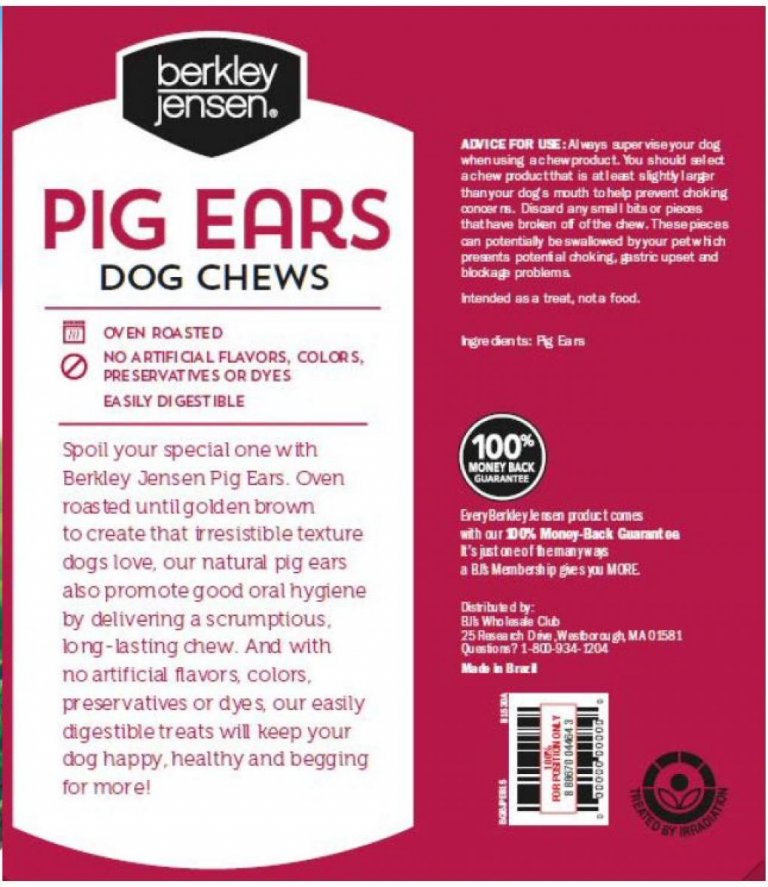

September 3, 2019 — Dog Goods USA is expanding its recent recall to include all 30-packs of Berkley Jensen brand pig ear dog chews sold at BJ’s Wholesale Club stores due to possible contamination with Salmonella.

The previous recall is being expanded after testing by Rhode Island Department of Health found Salmonella bacteria in Berkley Jensen brand pig ear pet chews.

What’s Being Recalled?

Dog Goods USA LLC of Tobyhanna, PA, has been contacted by the FDA and is conducting a voluntary recall of the following products: non-irradiated bulk and packaged pig ears branded Chef Toby Pig Ears with the lot codes indicated below.

The affected products were distributed nationwide in retail stores.

What Caused the Recall?

According to the company, Dog Goods USA purchased the affected treats from a single supplier in Brazil from September 2018 through August 2019.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, together with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and State partners, is investigating a link between pig ear pet treats and human cases of salmonellosis.

About Salmonella

Healthy people infected with Salmonella should monitor themselves for some or all of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramping and fever.

Rarely, Salmonella can result in more serious ailments, including arterial infections, endocarditis, arthritis, muscle pain, eye irritation, and urinary tract symptoms.

Consumers exhibiting these signs after having contact with this product should contact their healthcare providers.

Pets with Salmonella infections may be lethargic and have diarrhea or bloody diarrhea, fever and vomiting.

Some pets will have only decreased appetite, fever and abdominal pain.

Infected but otherwise healthy pets can be carriers and infect other animals and humans.

If your pet has consumed the recalled product and has these symptoms, please contact your veterinarian.

For more information and Salmonella and its symptoms and health risks, please refer to the following link: https://www.dfs.gov/animal-veterinary/news-events/fda-investigates-contaminated-pig-ear-pet-treats-connected-human-salmonella-infections.

Dog Goods Company Statement

The following statement has been provided by the company:

Dog Goods has also launched an internal investigation to determine, when and where the Products may have been contaminated.

To date, this internal investigation has not indicated any vulnerability in the company’s practices, including but not limited to the inspection, handling and storage of the Products.

Nonetheless, Dog Goods will continue to investigate the matter, collaborate fully with the FDA and the CDC, and provide further information to its customers and the public as appropriate.

What to Do?

Consumers who have purchased the products are urged to return them to the place of purchase for a full refund.

Consumers with questions may contact the company at 786-401-6533 from Monday to Friday, 9 AM ET through 5 PM ET.

U.S. citizens can report complaints about FDA-regulated pet food products by calling the consumer complaint coordinator in your area.

Or go to https://www.fda.gov/petfoodcomplaints.

Canadians can report any health or safety incidents related to the use of this product by filling out the Consumer Product Incident Report Form.

ooOOoo

Well, there are too many of these salmonella complaints if you ask me.

But it’s better to send out these FDA alerts than not to.

Again, please share as far and wide as you can.

Another FDA warning about a dog food.

Specifically Aunt Jeni’s Home Made frozen raw pet food.

Here are the details.

ooOOoo

August 30, 2019 — The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is warning pet ownersnot to feed their pets certain lots of Aunt Jeni’s Home Made frozen raw pet food.

That’s because 2 samples collected during an inspection of the company’s product tested positive for Salmonella and/or Listeria monocytogenes.

FDA is issuing this warning since these lots of Aunt Jeni’s Home Made frozen raw pet food represent a serious threat to both human and animal health.

Because the products are sold and stored frozen, FDA is concerned that people may still have them in their possession.

No product images have been provided by the FDA or the company.

Which Products Are Affected?

The affected products include:

Aunt Jeni’s Home Made pet foods are sold frozen both online and through various retail locations. Lot codes are printed on the lower right corner of the front of each bag.

About Salmonella

Salmonella is a bacterium that can cause illness and death in humans and animals, especially those who are very young, very old, or have weak immune systems.

According to CDC, people infected with Salmonella can develop diarrhea, fever and abdominal cramps.

Most people recover without treatment. However, in some people, the diarrhea may be so severe that they need to be hospitalized.

In some patients, the Salmonella infection may spread from the intestines to the blood stream and then to other body sites unless the person is treated promptly with antibiotics.

Consult your health care provider if you have symptoms of Salmonella infection.

Pets do not always display symptoms when infected with Salmonella.

However, signs can include vomiting, diarrhea (which may be bloody), fever, loss of appetite and/or decreased activity level.

If your pet has these symptoms, consult a veterinarian promptly.

You should also be aware that infected pets can shed the bacteria in their feces and saliva without showing signs of being sick, further contaminating the household environment.

About Listeria

Like Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes is another bacterium that can cause illness and death in humans and animals, especially those who are pregnant, very young, very old, or have weak immune systems.

According to CDC, listeriosis in humans can cause a variety of symptoms, depending on the person and the part of the body affected.

Symptoms can include headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, and convulsions in addition to fever and muscle aches.

Pregnant women typically experience only fever and other flu-like symptoms, such as fatigue and muscle aches.

However, infections during pregnancy can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, premature delivery, or life-threatening infection of the newborn.

Pregnant women and their newborns, adults age 65 and older, and people with weakened immune systems are more likely to get sick with listeriosis.

Anyone with symptoms of listeriosis should contact a health care provider.

Listeria infections are uncommon in pets. However, they are still possible.

Symptoms may include mild to severe diarrhea, anorexia, fever, nervous, muscular and respiratory signs, abortion, depression, shock and death.

Pets do not need to display symptoms to be able to pass Listeria on to their human companions.

As with Salmonella, infected pets can shed Listeria in their feces and saliva without showing signs of being sick, further contaminating the household environment.

What to Do?

If you have any of the affected product, stop feeding it to your pets and throw it away in a secure container where other animals, including wildlife, cannot access it.

Consumers who have had this product in their homes should clean refrigerators and freezers where the product was stored.

Clean and disinfect all bowls, utensils, food prep surfaces, pet bedding, toys, floors, and any other surfaces that the food or pet may have had contact with.

Because animals can shed the bacteria in the feces when they have bowel movements, it’s important to clean up the animal’s feces in yards or parks where people or other animals may become exposed.

Consumers should thoroughly wash their hands after handling the affected product or cleaning up potentially contaminated items and surfaces.

U.S. citizens can report complaints about FDA-regulated pet food products by calling the consumer complaint coordinator in your area.

Or go to https://www.fda.gov/petfoodcomplaints.

Canadians can report any health or safety incidents related to the use of this product by filling out the Consumer Product Incident Report Form.

ooOOoo

There’s a great deal of useful information contained in this recall.

As always, please share as much as you can.

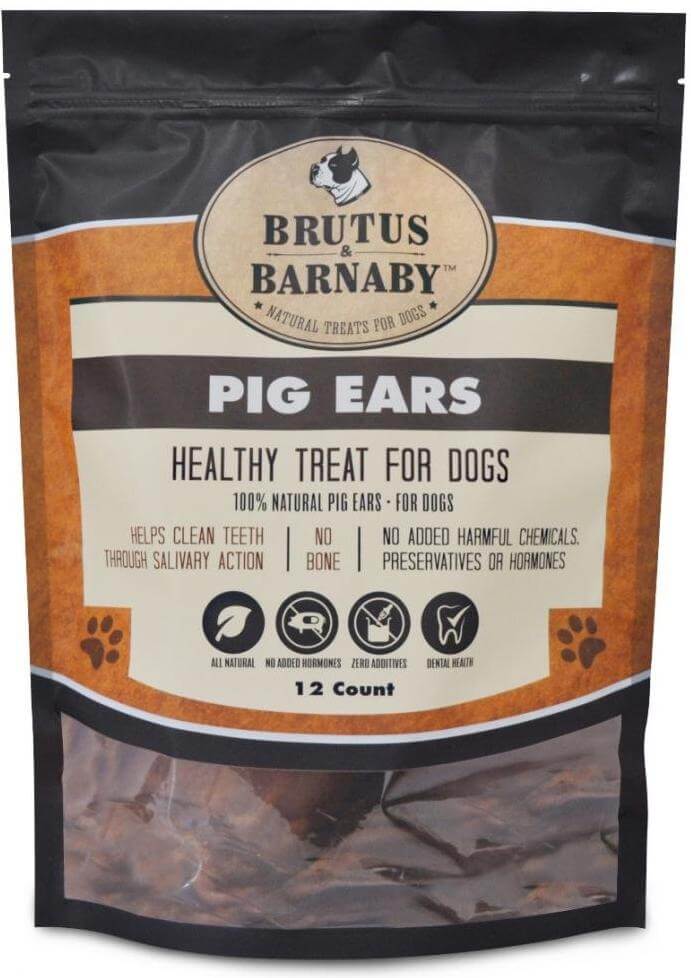

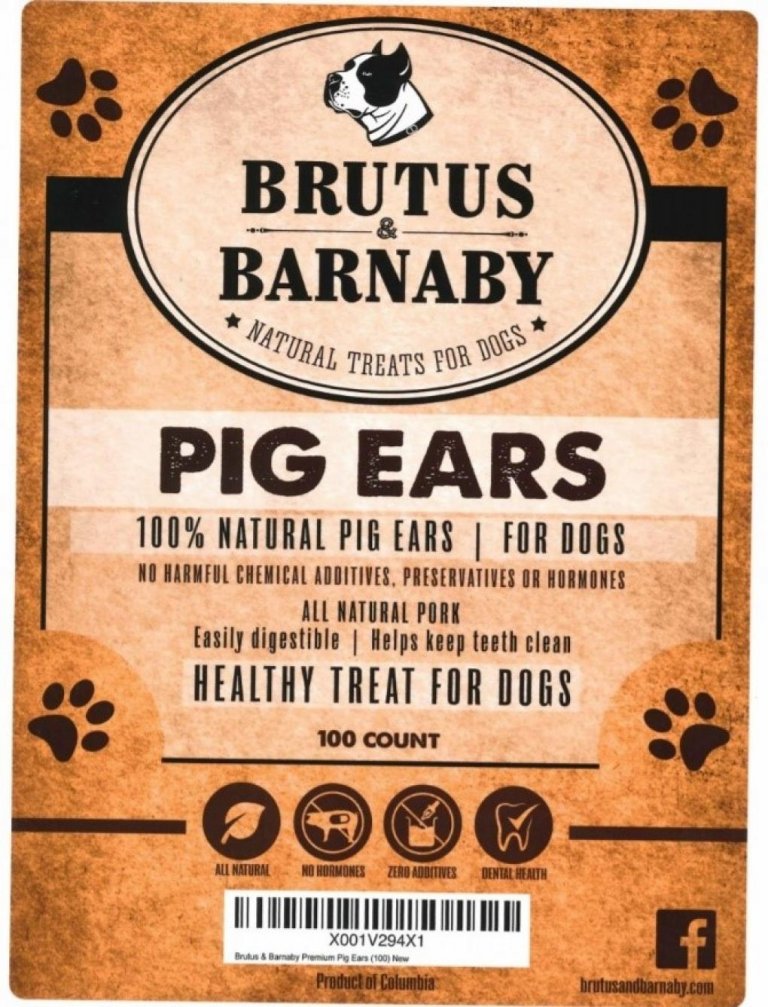

Because they have the potential to be contaminated with Salmonella bacteria.

Yet another recall.

ooOOoo

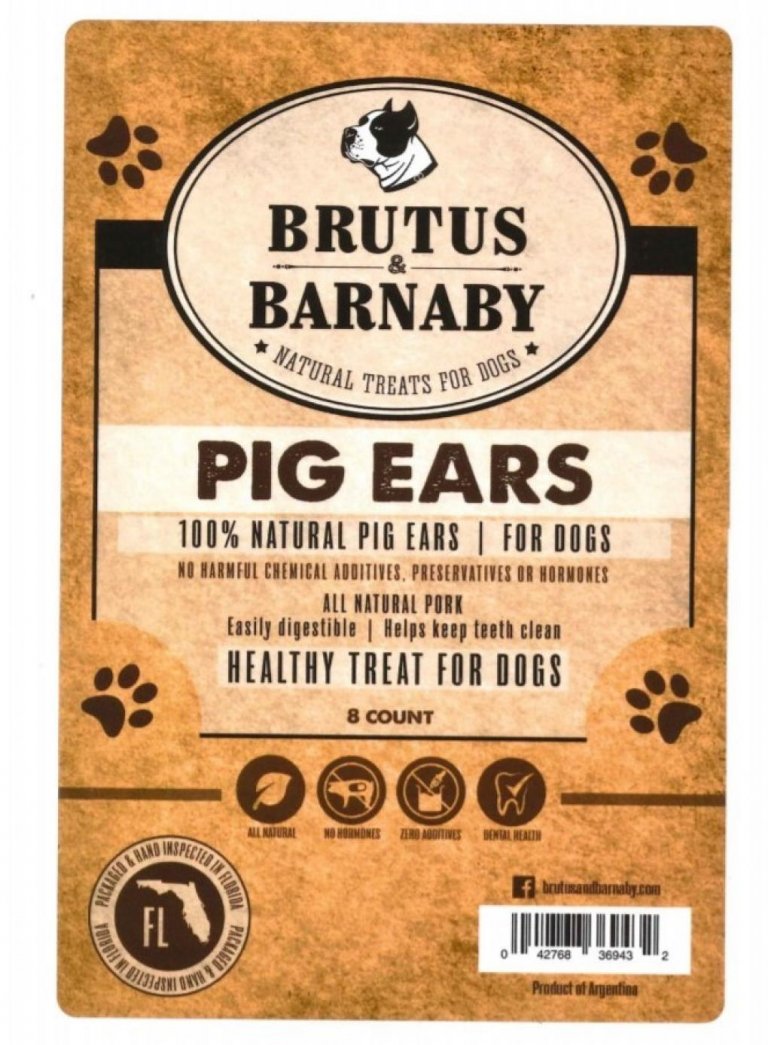

August 27, 2019 — Brutus & Barnaby LLC of Clearwater, Florida, is recalling all size variations of its Pig Ears for Dogs because they have the potential to be contaminated with Salmonella bacteria.

What Products Are Recalled?

Bags of Brutus & Barnaby Pig Ears were distributed throughout all states via Amazon.com, Chewy.com, Brutusandbarnaby.com and the brick and mortar Natures Food Patch in Clearwater, Florida.

The product label is identified by the company’s trademarked logo and reads “Pig Ears 100% Natural Treats for Dogs”.

The affected products were available in 4 sizes:

Brutus & Barnaby has ceased the production and distribution of the product as FDA and the company continue their investigation as to what caused the problem.

About Salmonella

Salmonella can affect animals eating the products and there is risk to humans from handling contaminated pet products, especially if they have not thoroughly washed their hands after having contact with the products or any surfaces exposed to these products.

Healthy people infected with Salmonella should monitor themselves for some or all of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramping and fever.

Rarely, Salmonella can result in more serious ailments, including arterial infections, endocarditis, arthritis, muscle pain, eye irritation, and urinary tract symptoms.

Consumers exhibiting these signs after having contact with this product should contact their healthcare providers.

Pets with Salmonella infections may be lethargic and have diarrhea or bloody diarrhea, fever, and vomiting.

Some pets will have only decreased appetite, fever and abdominal pain.

Infected but otherwise healthy pets can be carriers and infect other animals or humans.

If your pet has consumed the recalled product and has these symptoms, please contact your veterinarian.

What to Do?

Consumers who have purchased Brutus & Barnaby pig ears are urged to destroy any remaining product not yet consumed and to contact the place of purchase for a full refund.

Consumers with questions may contact the company at 800-489-0970 Monday through Friday, 9 am to 5 PM ET.

U.S. citizens can report complaints about FDA-regulated pet food products by calling the consumer complaint coordinator in your area.

Or go to https://www.fda.gov/petfoodcomplaints.

Canadians can report any health or safety incidents related to the use of this product by filling out the Consumer Product Incident Report Form.

ooOOoo

Once again, please share this as much as possible. One dog with salmonella is one dog too many!

An explanation of how old is that pet of yours.

One of the most frequent questions dog and cat owners get asked is how old is he or she. The pet that is!

And one of the most frequent concerns we have for our pets is how long will they live, as in what is their natural life span. Certainly, most of us realise that the larger dogs live slightly shorter lives but is that borne out in practice.

Well a recent professional article on The Conversation blogsite answered those questions.

ooOOoo

Clinical Instructor of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University

July 23rd, 2019

“Just how old do you think my dog is in dog years?” is a question I hear on a regular basis. People love to anthropomorphize pets, attributing human characteristics to them. And most of us want to extend our animal friends’ healthy lives for as long as possible.

It may seem like sort of a silly thing to ponder, born out of owners’ love for their pets and the human-animal bond between them. But determining a pet’s “real” age is actually important because it helps veterinarians like me recommend life-stage specific healthcare for our animal patients.

There’s an old myth that one regular year is like seven years for dogs and cats. There’s a bit of logic behind it. People observed that with optimal healthcare, an average-sized, medium dog would on average live one-seventh as long as its human owner – and so the seven “dog years” for every “human year” equation was born.

Not every dog is “average-sized” though so this seven-year rule was an oversimplification from the start. Dogs and cats age differently not just from people but also from each other, based partly on breed characteristics and size. Bigger animals tend to have shorter life spans than smaller ones do. While cats vary little in size, the size and life expectancy of dogs can vary greatly – think a Chihuahua versus a Great Dane.

Human life expectancy has changed over the years. And vets are now able to provide far superior medical care to pets than we could even a decade ago. So now we use a better methodology to define just how old rule of thumb that counted every calendar year as seven “animal years.”

Based on the American Animal Hospital Association Canine Life Stages Guidelines, today’s vets divide dogs into six categories: puppy, junior, adult, mature, senior and geriatric. Life stages are a more practical way to think about age than assigning a single number; even human health recommendations are based on developmental stage rather than exactly how old you are in years.

Canine life stages

Veterinarians divide a dog’s expected life span into six life stages based on developmental milestones. These age ranges are for a medium-sized dog; smaller dogs tend to live longer, while larger dogs tend to have shorter life expectancies.

|

STAGE

|

AGE (YEARS)

|

CHARACTERISTICS

|

|---|---|---|

| Puppy | 0 – 0.5 | Birth to sexual maturity |

| Junior | 0.5 – 0.75 | Reproductively mature, still growing |

| Adult | 0.75 – 6.5 | Finished growing, sexually and structurally mature |

| Mature | 6.5 – 9.75 | From middle to last 25% of expected lifespan |

| Senior | 9.75 -13 | Last 25% of life expectancy |

| Geriatric | over 13 | Beyond life span expectation |

Yet another dog food (treats) recall.

There seem to be more than normal just at present.

But anyway let’s go directly to the recall.

ooOOoo

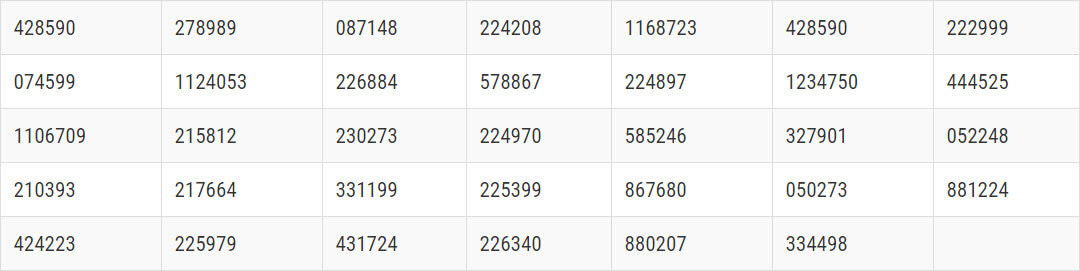

August 16, 2019 — Dog Goods USA LLC of Tobyhanna, PA, is recalling its Chef Toby Pig Ears Treats due to possible contamination with Salmonella bacteria and its associated health risks.

Chef Toby Pig Ears Treats

Product Images

The images below represent the labels of the recalled products:

What Caused the Recall?

Dog Goods bought the affected products from a single supplier in Brazil from September 2018 through August 2019 and distributed them nationwide in retail stores.

The FDA sampled pig ears manufactured by its supplier in Brazil and one sample tested positive for Salmonella.

As previously reported on this website, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), together with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and State partners, is investigating a suspected link between pig ear pet treats and human cases of salmonellosis.

What’s Being Recalled?

Dog Goods USA LLC is conducting a voluntary recall of the following bulk and packaged pig ears branded Chef Toby Pig Ears.

Product lot codes include: 428590, 278989, 087148, 224208, 1168723, 428590, 222999, 074599, 1124053, 226884, 578867, 224897, 1234750, 444525, 1106709, 215812, 230273, 224970, 585246, 327901, 052248, 210393, 217664, 331199, 225399, 867680, 050273, 881224, 424223, 225979, 431724, 226340, 880207, 334498.

About Salmonella

Healthy people infected with Salmonella should monitor themselves for some or all of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramping and fever.

Rarely, Salmonella can result in more serious ailments, including arterial infections, endocarditis, arthritis, muscle pain, eye irritation, and urinary tract symptoms.

Consumers exhibiting these signs after having contact with this product should contact their healthcare providers.

Pets with Salmonella infections may be lethargic and have diarrhea or bloody diarrhea, fever and vomiting.

Some pets will have only decreased appetite, fever and abdominal pain. Infected but otherwise healthy pets can be carriers and infect other animals and humans.

If your pet has consumed the recalled product and has these symptoms, please contact your veterinarian.

For more information about Salmonella and its symptoms and health risks, please refer to the following link: FDA Investigates Contaminated Pig Ear Pet Treats Connected to Human Salmonella Infections.

Company Statement

Dog Goods has also launched an internal investigation to determine if, when and where the Products may have been contaminated.

To date, this internal investigation has not indicated any vulnerability in the company’s practices, including but not limited to the inspection, handling and storage of the Products.

No illnesses have been linked to the products to date.

Nonetheless, Dog Goods will continue to investigate the matter, collaborate fully with the FDA and the CDC, and provide further information to its customers and the public as appropriate.

What to Do?

Consumers who have purchased the products are urged to return them to the place of purchase for a full refund.

Consumers with questions may contact the company at 786-401-6533 (ext 8000) from 9 am ET through 5 pm ET.

U.S. citizens can report complaints about FDA-regulated pet food products by calling the consumer complaint coordinator in your area.

Or go to https://www.fda.gov/petfoodcomplaints.

Canadians can report any health or safety incidents related to the use of this product by filling out the Consumer Product Incident Report Form.

ooOOOo

As always, please share this as far and wide as you can.

The jury is still out with regard to organic food being better for you, but …

Jeannie has been a vegetarian for years and I subscribed as soon as we met some eleven years ago. About two years ago we became vegan and non-dairy.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that being vegetarian or vegan means eating organically; it’s an assumption.

Now as it happens we also do our best to eat organically.

Is it healthier, all things being equal?

Well The Conversation recently published a post exploring this subject.

ooOOoo

Assistant Professor, Boise State University

August 16th, 2019

“Organic” is more than just a passing fad. Organic food sales totaled a record US$45.2 billion in 2017, making it one of the fastest-growing segments of American agriculture. While a small number of studies have shown associations between organic food consumption and decreased incidence of disease, no studies to date have been designed to answer the question of whether organic food consumption causes an improvement in health.

I’m an environmental health scientist who has spent over 20 years studying pesticide exposures in human populations. Last month, my research group published a small study that I believe suggests a path forward to answering the question of whether eating organic food actually improves health.

What we don’t know

According to the USDA, the organic label does not imply anything about health. In 2015, Miles McEvoy, then chief of the National Organic Program for USDA, refused to speculate about any health benefits of organic food, saying the question wasn’t “relevant” to the National Organic Program. Instead, the USDA’s definition of organic is intended to indicate production methods that “foster cycling of resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity.”

While some organic consumers may base their purchasing decisions on factors like resource cycling and biodiversity, most report choosing organic because they think it’s healthier.

Sixteen years ago, I was part of the first study to look at the potential for an organic diet to reduce pesticide exposure. This study focused on a group of pesticides called organophosphates, which have consistently been associated with negative effects on children’s brain development. We found that children who ate conventional diets had nine times higher exposure to these pesticides than children who ate organic diets.

Our study got a lot of attention. But while our results were novel, they didn’t answer the big question. As I told The New York Times in 2003, “People want to know, what does this really mean in terms of the safety of my kid? But we don’t know. Nobody does.” Maybe not my most elegant quote, but it was true then, and it’s still true now.

Studies only hint at potential health benefits

Since 2003, several researchers have looked at whether a short-term switch from a conventional to an organic diet affects pesticide exposure. These studies have lasted one to two weeks and have repeatedly shown that “going organic” can quickly lead to dramatic reductions in exposure to several different classes of pesticides.

Still, scientists can’t directly translate these lower exposures to meaningful conclusions about health. The dose makes the poison, and organic diet intervention studies to date have not looked at health outcomes. The same is true for the other purported benefits of organic food. Organic milk has higher levels of healthy omega fatty acids and organic crops have higher antioxidant activity than conventional crops. But are these differences substantial enough to meaningfully impact health? We don’t know. Nobody does.

Some epidemiologic research has been directed at this question. Epidemiology is the study of the causes of health and disease in human populations, as opposed to in specific people. Most epidemiologic studies are observational, meaning that researchers look at a group of people with a certain characteristic or behavior, and compare their health to that of a group without that characteristic or behavior. In the case of organic food, that means comparing the health of people who choose to eat organic to those who do not.

Several observational studies have shown that people who eat organic food are healthier than those who eat conventional diets. A recent French study followed 70,000 adults for five years and found that those who frequently ate organic developed 25% fewer cancers than those who never ate organic. Other observational studies have shown organic food consumption to be associated with lower risk of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, pre-eclampsia and genital birth defects.

The problem with drawing firm conclusions from these studies is something epidemiologists call “uncontrolled confounding.” This is the idea that there may be differences between groups that researchers cannot account for. In this case, people who eat organic food are more highly educated, less likely to be overweight or obese, and eat overall healthier diets than conventional consumers. While good observational studies take into account things like education and diet quality, there remains the possibility that some other uncaptured difference between the two groups – beyond the decision to consume organic food – may be responsible for any health differences observed.

What next?

When clinical researchers want to figure out whether a drug works, they don’t do observational studies. They conduct randomized trials, where they randomly assign some people to take the drug and others to receive placebos or standard care. By randomly assigning people to groups, there’s less potential for uncontrolled confounding.

My research group’s recently published study shows how we could feasibly use randomized trial methods to investigate the potential for organic food consumption to affect health.

We recruited a small group of pregnant women during their first trimesters. We randomly assigned them to receive weekly deliveries of either organic or conventional produce throughout their second and third trimesters. We then collected a series of urine samples to assess pesticide exposure. We found that those women who received organic produce had significantly lower exposure to certain pesticides (specifically, pyrethroid insecticides) than those who received conventional produce.

On the surface, this seems like old news but this study was different in three important ways. First, to our knowledge, it was the longest organic diet intervention to date – by far. It was also the first to occur in pregnant women. Fetal development is potentially the most sensitive period for exposures to neurotoxic agents like pesticides. Finally, in previous organic diet intervention studies, researchers typically changed participants’ entire diets – swapping a fully conventional diet for a fully organic one. In our study, we asked participants to supplement their existing diets with either organic or conventional produce. This is more consistent with the actual dietary habits of most people who eat organic food – occasionally, but not always.

Even with just a partial dietary change, we observed a significant difference in pesticide exposure between the two groups. We believe that this study shows that a long-term organic diet intervention can be executed in a way that is effective, realistic and feasible.

The next step is to do this same study but in a larger population. We would then want to assess whether there were any resulting differences in the health of the children as they grew older, by measuring neurological outcomes like IQ, memory and incidence of attention-deficit disorders. By randomly assigning women to the organic and conventional groups, we could be sure any differences observed in their children’s health really were due to diet, rather than other factors common among people who consume organic food.

The public is sufficiently interested in this question, the organic market is large enough, and the observational studies suggestive enough to justify such a study. Right now, we don’t know if an organic diet improves health, but based on our recent research, I believe we can find out.

ooOOoo

Fingers crossed that new research takes place.

Because good health at any age is precious!