Wishing you peace and happiness.

A Happy Christmas and a Very Happy New Year.

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Category: Religion

The concluding part of this essay by Patrice Ayme.

ooOOoo

Endowing aspects of the universe with spirituality, a mind of their own, is stupid in this day and age, only if one forgets there are natural laws underlying them. But if one wants to feel less alone and more purposeful, it is pretty smart.

Patrice Ayme

Here is the inventor of monotheism: Nefertiti. Once a fanatic of Aten, the sun god, she turned cautious, once Pharaoh on her own, backpedalled and re-authorized Egyptian polytheism. (The sun-God, Sol Invictis, was revived by Roman emperor Dioclesian 17 centuries later, in his refounding of Romanitas and the empire. His ultra young successor and contemporary, emperor Constantine, used the revived monotheism to impose his invention of Catholicism. Funny how small the conceptual world is.)

***

The preceding part (see Part One yesterday} contains many iconoclastic statements which made the Articial Intelligence (AI) I consulted with try to correct me with what were conventional, but extremely erroneous, ill-informed data points. AI also use the deranged upside down meta-argument that it is well-known that Christianism is not like that, so I have got to be wrong. Well, no, I was raised as a Catholic child in two different Muslim countries, and also in a Pagan one; the Muslim faiths I knew as child were as different from Suny/Shiah faiths as Christianism is, overall, from Islamism. In other words, I know the music of monotheism. So here are:

***

TECHNICAL NOTES:

[1] To speak in philosophical linguo, we capture two civilizational “ontologies” (logic of existence):

[2] Paganus, in a religious sense, appears first in the Christian author Tertullian, around 202 CE, to evoke paganus in Roman military jargon for ‘civilian, incompetent soldier‘ by opposition to the competent soldiers (milites) of Christ that Tertullian was calling for.

[3] ‘FAIR OF FACE, Joyous with the Double Plume, Mistress of Happiness, Endowed with Favour, at hearing whose voice one rejoices, Lady of Grace, Great of Love, whose disposition cheers the Lord of the Two Lands.‘

With these felicitous epithets, inscribed in stone more than 3,300 years ago, on the monumental stelae marking the boundaries of the great new city at Tell el Amarna on the Nile in central Egypt, the Pharaoh Akhenaten extolled his Great Royal Wife, the chief queen, the beautiful Nefertiti.

Nefertiti (‘the beautiful one has come‘) co-ruled Egypt with her older (and apparently famously ugly, deformed by disease) husband. Egypt was at its wealthiest. She was considered to be a DIVINITY. All her life is far from known, and revealed one fragment of DNA or old text at a time. She ruled as sole Pharaoh after her husband’s death, and seems to have offered to marry the Hittite Prince (as revealed by a recently found fragment: ”I do not wish to marry one of my subjects. I am afraid…” she confessed in a letter to the amazed Hittite emperor.). She apparently decided to re-allow the worship of the many Egyptian gods, and her adoptive son and successor Tutankhaten switched his name to Tutankhamen). Both her and Tutankhamen died, and they were replaced by a senior top general of Akhenatten who both relieved the dynasty from too much inbreeding (hence the deformed Akhenaten) and too much centralism focused on the sun-disk (‘Aten’)

[4] Those who do not know history have a small and ridiculous view of FASCISM. Pathetically they refer to simpletons, such as Hitler and Mussolini, to go philosophical on the subject.. Google’s Gemini tried to pontificate that ‘labeling the structure of monotheism (especially its early forms) as ‘fascistic’ is anachronistic and highly inflammatory. Fascism is a specific 20th-century political ideology. While the author means authoritarian and hierarchical, using ‘fascistic’ distracts from the historical and philosophical points by introducing modern political baggage. It would be clearer and less polemical to stick to ‘Hierarchical’ or ‘Authoritarian-Centralized.‘

I disagree virulently with this cognitive shortsightedness of poorly programmed AI. The Romans were perfectly aware of the meaning that the faces symbolized (they got them from the Etruscans). So were the founders of the French and American republics aware of the importance of fascism and the crucial capabilities it provided, the powerful republics which, in the end, succeeded the Roman Republic (which died slowly under the emperors until it couldn’t get up); those two republics gave the basic mentality now ruling the planet.

Fascism is actually an instinct. Its malevolent and dumb confiscation by ignorant morons such as Hitler and Mussolini ended pathetically under the blows of regimes (the democracies on one side, the fascist USSR on the other) which were capable of gathering enough, and much more, and higher quality fascism of their own to smother under a carpet of bombs the cretinism of the genocidal tyrants. It is actually comical, when reading old battles stories, to see the aghast Nazis out-Nazified by their Soviet opponents (discipline on the Soviet side was a lethal affair at all and any moment.) Or then to see SS commanders outraged by the ferocity of their US opponents. At Bir Hakeim, a tiny French army, 3,000 strong, buried in the sands, blocked the entire Afrika Korps and the Italian army, for weeks, under a deluge of bombs and shells, killing the one and only chance the Nazis had to conquer the Middle East. Hitler ordered the survivors executed, Rommel, who knew he was finished, disobeyed him.

***

Early Christianism was highly genocidal. The Nazi obsession with the Jews was inherited from Nero (who, unsatisfied with just crucifying Christians (64 CE), launched the annihilation wars against Israel) and then the Christians themselves. There were hundreds of thousands of Samaritans, a type of Jew, with their own capital and temple (above Haifa). Warming up, after centuries of rage against civilization, the Christians under emperor Justinian, in the Sixth Century, nearly annihilated the Samaritans; a genocide by any definition.

Later, by their own count, at a time when Europe and the greater Mediterranean counted around 50 million inhabitants, the Christians, over centuries, killed no less than 5 million Cathars from Spain to Anatolia. Cathars, the pure ones in Greek (a name given to them by their genociders), were a type of Christian). In France alone, in a period of twenty years up to a million were killed, (not all Cathars, but that accentuates the homicidal character). As a commander famously said: ”Tuez les tous, Dieu reconnaitra les siens” (Kill them all, God will recognize his own). The anti-Cathars genocide drive in France, an aptly named ‘crusade‘, something about the cross, lasted more than a century (and boosted the power of the Inquisition and the Dominicans). The extinction of Catharism was so great that we have only a couple of texts left.

Want to know about Christianism? Just look at the torture and execution device they brandish, the cross. Christianism literally gave torture and execution a bad name, and it’s all the most cynical hypocrisy hard at work.

And so on. To abstract it in an impactful way, one could say that much of Christianism instigated Nazism. That’s one of the dirty little secrets of history, and rather ironical as the dumb Hitler was anti-Christian, and still acted like one, unbeknownst to himself, his public, and his critiques; those in doubt can consult the descriptions of the Crusades by the Franks themselves, when roasting children was found to relieve hunger.

Chroniclers like Radulph of Caen (a Norman historian writing around 1118) described it vividly: “In Ma’arra our troops boiled pagan adults in cooking-pots; they impaled children on spits and devoured them grilled.” Other sources, such as Joinville, Fulcher of Chartres and Albert of Aachen, corroborate the desperation and brutality, though they express varying degrees of horror or justification. These acts were not systematic policy but extreme responses to the hunger and chaos of war, and they were preserved in Frankish narratives as part of the Crusade’s grim legacy. (There were also cases of cannibalism in WW2).

Christianism, when not actively genocidal, certainly instigated a mood, a mentality, of genocide; read Roman emperor Theodosius I about heresy. Here is the end of Theodosius’ famous quote: ‘According to the apostolic teaching and the doctrine of the Gospel, let us believe in the one deity of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, in equal majesty and in a holy Trinity. We order the followers of this law to embrace the name of Catholic Christians; but as for the others, we judge them to be demented and ever more insane (dementes vesanosque iudicantes), we decree that they shall be branded with the ignominious name of heretics, and shall not presume to give to their conventicles the name of churches. They will suffer in the first place the chastisement of the divine condemnation and in the second the PUNISHMENT OF OUR AUTHORITY which in accordance with the will of Heaven WE SHALL DECIDE TO INFLICT.‘

The ‘Men In Black‘ of the Fourth Century destroyed books, libraries and intellectuals, ensuring the smothering of civilization, as intended (destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria, the world’s largest library) around 391 CE. Contemporary writers like Eunapius and Libanius lamented the ‘rage for destruction’ of the Men In Black. Some non-Christian texts were preserved in monasteries, true, but the point is that Christianism made possible the destruction of non-Yahweh knowledge. This is the problem king David himself already had, the fascism, the power obsessed little mind of Yahweh. Monasteries were often built with a covert anti-Christian mentality, things were complicated. When queen Bathilde outlawed slavery (657 CE), her closest allies were bishops, yet she had to execute other, slave-holding bishops. She also founded and funded four monasteries. Soon the Frankish government passed a law enforcing secular teaching by religious establishments.

The uniforms of the Men In Black were copied later by the Dominicans (‘Black Friars’) who led the genocide of the Cathars, in co-operation with the Inquisition, also dressed in black, and then the SS. Luther. Saint Louis expressed explicitly that nothing would bring them more joy than Jews suffering to death. Saint Louis was more descriptive, evoking a knife planted in the belly of the unbeliever and great pleasure. In Joinville’s Life of Saint Louis (c. 1309), Louis recounts a story of a knight who, during a debate with Jews, stabbed one in the belly with a dagger, saying it was better to “kill him like that” than argue theology. Louis presented this approvingly as zeal for the faith, and wished he could partake. Although he warned, he wouldn’t do it, that would be illegal. With a faith like that Louis IX could only be canonized in 1297 CE. And, following Saint Louis’ hint, the Nazis removed his legal objection by changing the law in 1933, when they got to power.

Luther gave multiple and extensive ‘sincere advices‘ on how to proceed with the genocide of the Jews in his book: ”The Jews and their Lies”. Here is a sample: “If I had to baptize a Jew, I would take him to the bridge of the Elbe, hang a stone around his neck and push him over, with the words, ‘I baptize thee in the name of Abraham.”

But Musk’s AI, ‘Grok’ informed me that its basic axiom was that Christianism was never genocidal, but instead ‘suppressive‘. Then it thought hard for ‘nine seconds‘ to try to prove to me, with biased context, that I had exaggerated.

I had not.

***.

The entire church was into assassination madness, glorifying in its own cruelty; the chief assassin of Hypatia, a sort of Charlie Manson to the power 1000, was made into a saint: Saint Cyril. Cyril’s minions grabbed Hypatia who had just finished giving a lecture, dragged her in the streets, and stripped her clothing, and then stripped her of her own skin, flaying her with oysters shells, causing her demise. She was the top intellectual of the age. Hypatia met her torturous end in 415 CE. Cyril was made into a saint 29 years later, in 444 CE! With saints like that, who needs Hitler?

Not to say Catholicism was useless; the jealous and genocidal, yet loving and all-knowing Yahweh was always a good excuse to massacre savages and extend civilization on the cheap. The Teutonic Knights, finding the Yahweh fanatics known as Muslims too hard a nut to crack, regrouped in Eastern Germany and launched a very hard fought crusade against the Prussian Natives, who were Pagans. After mass atrocities on both sides, the Teutons won.

The Franks embraced the capabilities of the cross, fully. Having converted to Catholicism, they were in a good position to subdue other Germans, who were Arians (and that they did, submitting Goths and Burgonds, Ostrogoths and Lombards). Three centuries later, Charlemagne used Christianism as an instrument to kill Saxons on an industrial scale, in the name of God, to finally subdue them, after Saxons had terminally aggravated Romanitas for 800 years, driving Augustus crazy.

Charlemagne, in daily life, showing how relative Christianism was, and its true Jewish origins, used the nickname ‘David’ for king David, the monarch who refused to obey Yahweh, who had ordered David to genocidize a people (petty, jealous God Yahweh then tortured David’s son to death).

Charlemagne lived the life of a hardened Pagan, with a de-facto harem, etc. More viciously, Charlemagne passed laws pushing for secular, and thus anti-Christian education. Following in these respects a well-established Frankish custom. Charlemagne knew Christianism was a weapon, and he was careful to use it only on the Saxons; internally, there was maximum tolerance: Christians could become Jews, if they so wished.

PA

ooOOoo

I found the full essay quite remarkable. Jean has heard me rattle on about it numerous times since I first read the essay on November 2nd. I sincerely hope you will read it soon.

Finally, let me reproduce what I wrote in a response to Patrice’s post:

Patrice, in your long and fascinating article, above, you have educated me in so many ways. My mother was an atheist and I was brought up in likewise fashion. But you have gone so much further in your teachings.

Your article needs a further reading. But I am going to share it with my readers on LfD so many more can appreciate what you have written. Plus, I am going to republish it over two days.

Thank you, thank you, thank you!

A brilliant essay by Patrice Ayme.

Patrice writes amazing posts, some of which are beyond me. But this one, The Personification Of The World, PAGANISM, Gives Us Friends Everywhere, is incredible.

My own position is that my mother and father were atheists and I was brought up as one. Apart from a slip-up when I was married to my third wife, a Catholic, and she left me and I thought that by joining the Catholic church I might win her back. (My subconcious fear of rejection.)

My subconscious fear of rejection was not revealed to me until the 50th anniversary of my father’s death in 2006 when I saw a local psychotherapist. Then I met Jean in December, 2007 and she was the first woman I truly loved!

Back to the essay; it is a long essay and I am going to publish the first half today and the second half tomorrow. (And I have made some tiny changes.)

ooOOoo

The Personification Of The World, PAGANISM, Gives Us Friends Everywhere

Abstract: Personification of the world (polytheism/paganism) is more pragmatic, psychologically rewarding, and ecologically sound than the hierarchical, abstracted structure of monotheism, which the author labels “fascistic.” [4]

***

Switching to a single fascist God, Ex Pluribus Unum, a single moral order replacing the myriad spirits of the world, was presented as a great progress: now everybody could, should, line up below the emperor, God’s representative on Earth, and obey the monarch and his or her gang. The resulting organization was called civilization. Submitting to God was the only way Rome could survive, because it provided a shrinking army and tax base with more authority than it deserved.

However peasants had to predict the world and it was more judicious to personalize aspects of it. The resulting logico-emotional relationship had another advantage: the supportive presence of a proximal Gods… All over!.[1]

***

personification

/pəˌsɒnɪfɪˈkeɪʃn/ noun

1.the attribution of a personal nature or human characteristics to something non-human, or the representation of an abstract quality in human form.

***

Before Christianism, Gods were everywhere. When the Christians took over, they imposed their all powerful, all knowing Jewish God. Some present the Jewish God as a great invention, symbolizing some sort of progress of rationality that nobody had imagined before.

However, the single God concept was not that new. Even Americans had it in North America, as the chief of God, the Aztecs, had a similar concept, and even Zeus was a kind of chief God. Zoroastrianism had Ahura Mazda, who did not control Angra Manyu, but still was somewhat more powerful. The Hindus had Vishnu and his many avatars.

Eighteen centuries before those great converters to Christianism, Constantine, Constantius II, and Theodosius I, there was an attempt to forcefully convert the Egyptians to a single God. Pharaoh Akhenaten’s monotheistic experiment (worship of Aten) caused turmoil and was erased by his immediate successors.

According to the latest research it seems likely that the famous Nefertiti became a Pharaoh on her own, after the death of her husband, and retreated from monotheism by re-establishing Egyptian polytheism [3]. In the fullness of time, the infernal couple got struck by what the Romans, 15 centuries later, would call damnatio memoriae. Their very names and faith were erased from hundreds of monuments

Shortly after the Aten episode, there was another confrontation between polytheism and monotheism. The colonizers of Gaza were apparently Greek, of Aegean origin, and, as such, over more than a millennium of conflict with the Jewish states in the hills, Greek Gods confronted Yahweh. The Greeks obviously did not see Yahweh as a major conceptual advance, as they did not adopt Him (until Constantine imposed Him, 15 centuries later).

While the area experienced enormous turmoil, including the permanent eclipse of Troy after the war with Greece (see Homer), and later its replacement by Phrygia, then followed by the Bronze Age collapse, then the rise of Tyre, and the Assyrian conquest, the Greeks survived everything, and their civilization kept sprawling (the early Christian writings were in Greek).

Ultimately, the lack of ideological bending, the obsession with pigs and other silliness, helped to bring devastating Judeo-Roman wars. By comparison, the much larger Gaul bent like a reed when confronted with the Greco-Romans, absorbing the good stuff. Mercury, the God of trade, preceded Roman merchants. Gaul didn’t take religion too seriously, and went on with civilizational progress.

The lack of elasticity of the single God religion of the Jews brought their quasi-eradication by Rome; Judaism was tolerated, but Jewish nationalism got outlawed. By comparison, the Greeks played the long game, and within a generation or so of Roman conquest, they had spiritually conquered their conqueror. Christianism was actually an adaptation of Judaism to make Yahweh conquer the heart and soul of fascist Rome.

***

To have Gods everywhere? Why not? Is not the Judeo-Christian God everywhere too? Doesn’t it speak through fountains, and the immensity of the desert, and the moon, and the stars, too?

***

Yahweh, the Jewish God Catholic Romans called “Deus” was deemed to be also the ultimate love object. Yahweh had promised land to the Jews, Deus promised eternal life of the nicest sort – To all those who bought the program.

Christians were city dwellers and their power over the countryside and barbarians came from those who had imposed Christianism, the imperial powers that be (at the time, more than 90% of the people worked in agriculture). Already as a teenager, Constantine, a sort of superman born from imperial purple, terrified the court which was supposed to hold him hostage. Such a brute and excellent general could only get inspired by Yahweh’s dedication to power.

The country dwellers, the villagers, disagreed that they needed to submit to a God organized, celebrated and imposed by the all-powerful government (god-vernment?). In classical Latin paganus meant ‘villager, rustic; civilian, non-combatant’. In late imperial Latin it came to mean non-Judeo-Christian (and later non-Judeo-Christo-Islamist) [2].

Christianism found it very difficult to penetrate the countryside, where the food was produced. It never quite succeeded (Even in Muslim Albania, Pagan rituals survived until the 20th century; much of the cult of saints is barely disguised Paganism).

Peasants knew that power was distributed throughout nature, and they had to understand those powers, thus love them – That enabled them to predict phenomena.

Peasants could ponder the mood of a river, and even predict it; flooding was more of a possibility in some circumstances, and then it was no time to indulge in activities next to the river. Peasants had to guess the weather, and the earlier, the better. Peasants had to know which part of the astronomical cycle they were in, to be able to plant crops accordingly; that was not always clear just looking outside, but the stars would tell and could be trusted to tell the truth.

We can be friends to human beings, and sometimes it’s great, but sometimes we feel betrayed and abandoned. But a mountain or a sea? They will always be there, they are not running away, they are never deliberately indifferent, and generally exhibit predictable moods. It is more pragmatic and rewarding to love them more rather than an abstract Dog in Heavens. Call them Gods if you want.

ooOOoo

Part two will be published tomorrow.

I am publishing the notes, on both days, so you can look them up now rather than waiting another day.

TECHNICAL NOTES:

[1] To speak in philosophical linguo, we capture two civilizational ‘ontologies’ (logic of existence):

[2] Paganus, in a religious sense, appears first in the Christian author Tertullian, around 202 CE, to evoke paganus in Roman military jargon for ‘civilian, incompetent soldier‘ by opposition to the competent soldiers (milites) of Christ that Tertullian was calling for.

[3] ‘FAIR OF FACE, Joyous with the Double Plume, Mistress of Happiness, Endowed with Favour, at hearing whose voice one rejoices, Lady of Grace, Great of Love, whose disposition cheers the Lord of the Two Lands.‘

With these felicitous epithets, inscribed in stone more than 3,300 years ago on the monumental stelae marking the boundaries of the great new city at Tell el Amarna on the Nile in central Egypt, the Pharaoh Akhenaten extolled his Great Royal Wife, the chief queen, the beautiful Nefertiti.

Nefertiti (‘the beautiful one has come‘) co-ruled with her older (and apparently famously ugly, deformed by disease) husband, Egypt. Egypt was at its wealthiest. She was considered to be a DIVINITY. All her life is far from known, and revealed one fragment of DNA or old text at a time. She ruled as sole Pharaoh after her husband’s death, and seems to have offered to marry the Hittite Prince (as revealed by a recently found fragment: ”I do not wish to marry one of my subjects. I am afraid…” she confessed in a letter to the amazed Hittite emperor). She apparently decided to re-allow the worship of the many Egyptian gods and her adoptive son and successor Tutankhaten switched his name to Tutankhamen. Both her and Tutankhamen died, and they were replaced by a senior top general of Akhenatten who both relieved the dynasty from too much inbreeding (hence the deformed Akhenaten) and too much centralism focused on the sun-disk (‘Aten’).

[4] Those who do not know history have a small and ridiculous view of FASCISM. Pathetically they refer to simpletons, such as Hitler and Mussolini, to go philosophical on the subject. Google’s Gemini tried to pontificate that ‘labeling the structure of monotheism (especially its early forms) as ‘fascistic’ is anachronistic and highly inflammatory. Fascism is a specific 20th-century political ideology. While the author means authoritarian and hierarchical, using ‘fascistic’ distracts from the historical and philosophical points by introducing modern political baggage. It would be clearer and less polemical to stick to ‘Hierarchical’ or ‘Authoritarian-Centralized’.

A fascinating article makes a fundamental point.

My mother and father were atheists so when I was born in 1944 it was obvious that I would be brought up as an atheist. Same for my sister, Elizabeth, born in 1948. It was amazing that when I met Jean in Mexico in 2007 that she, too, was an atheist. That was on top of the fact that we were both born in North London some 26 miles apart. Talk about fate!

So naturally my attention was drawn to a recent article in Free Enquiry magazine, Thinking Made Me an Atheist.

That article opens as follows:

I was abused as a child. The abuse to which I was subjected is called “child indoctrination,” a type of brainwashing considered noble and necessary and, therefore, the most natural thing in the world.

My mother took me to the Seventh-day Adventist Church, an American denomination known for keeping the Sabbath and emphasizing the advent, or return, of Jesus. Adventists boast that they are the only ones to interpret the Bible the way its author wanted. Consequently, they deem themselves the most special creatures to God—so special that they’ll soon arouse the envy and wrath of all other denominations and religions, which, under the command of the beasts of Revelation (the American government and the Catholic Church), will persecute them. Adventists believe that the Earth was created in six days, that it is 6,000 years old, and that dinosaurs are extinct because they were too big to be saved on Noah’s ark.

It closes thus:

I don’t want to believe; I want to know. Atheism is a natural result of intellectual honesty.

The author of the article, Paulo Bittencourt is described as:

Paulo Bittencourt was born in Castro, Brazil, spent his childhood in Rio de Janeiro, and studied theology in São Paulo. Close to becoming a pastor, he went on an adventure to Europe and ended up settling in Austria, where he trained as an opera singer. Bittencourt is the author of the books Liberated from Religion: The Inestimable Pleasure of Being a Freethinker and Wasting Time on God: Why I Am an Atheist.

So once again, do read this article.

We sincerely believe there is no god!

I love this!

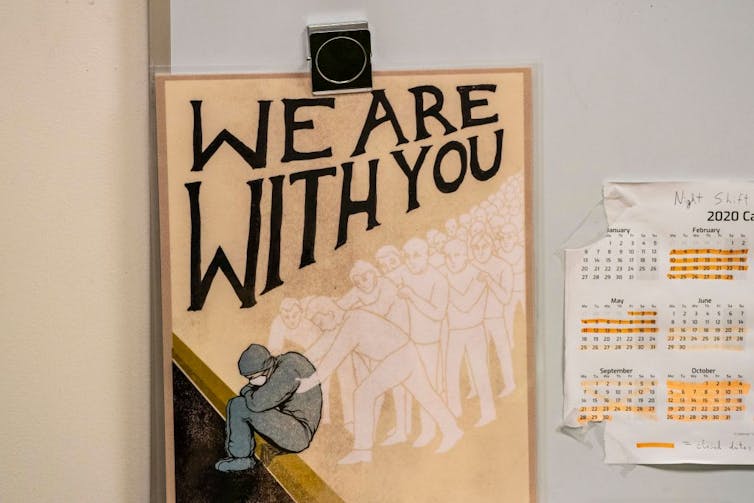

I am writing this having listened to a programme on BBC Radio 4. (Was broadcast on Radio 4 on Tuesday, August 13th.) It shows how many, many people can have a really positive response to a dastardly negative occurrence such as the Covid outbreak or a pandemic.

ooOOoo

Mark Honigsbaum, City, University of London

Every Friday, volunteers gather on the Albert Embankment at the River Thames in London to lovingly retouch thousands of red hearts inscribed on a Portland stone wall directly opposite the Houses of Parliament. Each heart is dedicated to a British victim of COVID. It is a deeply social space – a place where the COVID bereaved come together to honour their dead and share memories.

The so-called National Covid Memorial Wall is not, however, officially sanctioned. In fact, ever since activists from COVID-19 Bereaved Families for Justice (CBFFJ) daubed the first hearts on the wall in March 2021 it has been a thorn in the side of the authorities.

Featured in the media whenever there is a new revelation about partygate, the wall is a symbol of the government’s blundering response to the pandemic and an implicit rebuke to former prime minister Boris Johnson and other government staff who breached coronavirus restrictions.

As one writer put it, viewed from parliament the hearts resemble “a reproachful smear of blood”. Little wonder that the only time Johnson visited the wall was under the cover of darkness to avoid the TV cameras. His successor Rishi Sunak has been similarly reluctant to acknowledge the wall or say what might take its place as a more formal memorial to those lost in the pandemic.

Though in April the UK Commission on COVID Commemoration presented Sunak with a report on how the pandemic should be remembered, Sunak has yet to reveal the commission’s recommendations.

Lady Heather Hallett, the former high court judge who chairs the public inquiry into COVID, has attempted to acknowledge the trauma of the bereaved by commissioning a tapestry to capture the experiences of people who “suffered hardship and loss” during the pandemic. Yet such initiatives are no substitute for state-sponsored memorials.

This political vacuum is odd when you consider that the United Kingdom, like other countries, engages in many other commemorative activities central to national identity. The fallen of the first world war and other military conflicts are commemorated in a Remembrance Sunday ceremony held every November at the Cenotaph in London, for example.

But while wars lend themselves to compelling moral narratives, it is difficult to locate meaning in the random mutations of a virus. And while wars draw on a familiar repertoire of symbols and rituals, pandemics have few templates.

For instance, despite killing more than 50 million globally, there are virtually no memorials to the 1918-1919 “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Nor does the UK have a memorial to victims of HIV/AIDS. As the memory studies scholar Astrid Erll puts it, pandemics have not been sufficiently “mediated” in collective memory.

As a rule, they do not feature in famous paintings, novels or films or in the oral histories passed down as part of family lore. Nor are they able to draw on familiar cultural materials such as poppies, gun carriages, catafalques and royal salutes. Without such symbols and schemata, Erll argues, we struggle to incorporate pandemics into our collective remembering systems.

This lacuna was brought home to me last September when tens of thousands of Britons flocked to the south bank of the Thames to pay their respects to Britain’s longest serving monarch. By coincidence, the police directed the queue for the late Queen’s lying-in-state in Westminster Hall over Lambeth Bridge and along Albert Embankment.

But few of the people I spoke to in the queue seemed to realise what the hearts signified. It was as if the spectacle of a royal death had eclipsed the suffering of the COVID bereaved, rendering the wall all but invisible.

Another place where the pandemic could be embedded in collective memory is at the public inquiry. Opening the preliminary hearing last October into the UK’s resilience and preparedness for a pandemic, Lady Hallett promised to put the estimated 6.8 million Britons mourning the death of a family member or friend to COVID at the heart of the legal process. “I am listening to them; their loss will be recognised,” she said.

But though Lady Hallett has strategically placed photographs of the hearts throughout the inquiry’s offices in Bayswater and has invited the bereaved to relate their experiences to “Every Story Matters”, the hearing room is dominated by ranks of lawyers. And except when a prominent minister or official is called to testify, the proceedings rarely make the news.

This is partly the fault of the inquiry process itself. The hearings are due to last until 2025, with the report on the first stage of the process not expected until the summer of 2024. As Lucy Easthope, an emergency planner and veteran of several disasters, puts it: “one of the most painful frustrations of the inquiry will be temporal. It will simply take too long.”

The inquiry has also been beset by bureaucratic obfuscation, not least by the Cabinet Office which attempted (unsuccessfully in the end) to block the release of WhatsApp messages relating to discussions between ministers and Downing Street officials in the run-up to lockdown.

To the inquiry’s critics, the obvious parallel is with the Grenfell inquiry, which promised to “learn lessons” from the devastating fire that engulfed the west London tower in 2017 but has so far ended up blurring the lines of corporate responsibility and forestalling a political reckoning.

The real work of holding the government to account and making memories takes place every Friday at the wall and the other places where people come together to spontaneously mourn and remember absent loved ones. These are the lives that demand to be “seen”. They are the ghosts that haunt our amnesic political culture.

Mark Honigsbaum, Senior Lecturer in Journalism, City, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

plus Wikipedia have a long article on the National Covid Memorial Wall. That then takes us to the website for the wall.

ooOOoo

As was written in the last sentence of the article; ‘They are the ghosts that haunt our amnesic political culture.‘

Humans are a strange lot and I most certainly count myself in!

Another very interesting post courtesy of The Conversation.

First of all, let me quote the opening two paragraphs from the WikiPedia entry on ‘intellectual humility’:

Intellectual humility is the acceptance that one’s beliefs and opinions could be wrong. Other characteristics that may accompany intellectual humility include a low concern for status and an acceptance of one’s intellectual limitations.

Intellectual humility (IH) is often described as an intellectual virtue. It is considered along with other perceived virtues and vices such as open-mindedness, intellectual courage, arrogance, vanity, and servility. It can be understood as lying between the opposite extremes of intellectual arrogance/dogmatism and intellectual servility/diffidence/timidity.

Now to the article that was published by The Conversation.

ooOOoo

Daryl Van Tongeren, Hope College

Mark Twain apocryphally said, “I’m in favor of progress; it’s change I don’t like.” This quote pithily underscores the human tendency to desire growth while also harboring strong resistance to the hard work that comes with it. I can certainly resonate with this sentiment.

I was raised in a conservative evangelical home. Like many who grew up in a similar environment, I learned a set of religious beliefs that framed how I understood myself and the world around me. I was taught that God is loving and powerful, and God’s faithful followers are protected. I was taught that the world is fair and that God is good. The world seemed simple and predictable – and most of all, safe.

These beliefs were shattered when my brother unexpectedly passed away when I was 27 years old. His death at 34 with three young children shocked our family and community. In addition to reeling with grief, some of my deepest assumptions were challenged. Was God not good or not powerful? Why didn’t God save my brother, who was a kind and loving father and husband? And how unfair, uncaring and random is the universe?

This deep loss started a period where I questioned all of my beliefs in light of the evidence of my own experiences. Over a considerable amount of time, and thanks to an exemplary therapist, I was able to revise my worldview in a way that felt authentic. I changed my mind, about a lot things. The process sure wasn’t pleasant. It took more sleepless nights than I care to recall, but I was able to revise some of my core beliefs.

I didn’t realize it then, but this experience falls under what social science researchers call intellectual humility. And honestly, it is probably a large part of why, as a psychology professor, I am so interested in studying it. Intellectual humility has been gaining more attention, and it seems critically important for our cultural moment, when it’s more common to defend your position than change your mind.

Intellectual humility is a particular kind of humility that has to do with beliefs, ideas or worldviews. This is not only about religious beliefs; it can show up in political views, various social attitudes, areas of knowledge or expertise or any other strong convictions. It has both internal- and external-facing dimensions.

Within yourself, intellectual humility involves awareness and ownership of the limitations and biases in what you know and how you know it. It requires a willingness to revise your views in light of strong evidence.

Interpersonally, it means keeping your ego in check so you can present your ideas in a modest and respectful manner. It calls for presenting your beliefs in ways that are not defensive and admitting when you’re wrong. It involves showing that you care more about learning and preserving relationships than about being “right” or demonstrating intellectual superiority.

Another way of thinking about humility, intellectual or otherwise, is being the right size in any given situation: not too big (which is arrogance), but also not too small (which is self-deprecation).

I know a fair amount about psychology, but not much about opera. When I’m in professional settings, I can embrace the expertise that I’ve earned over the years. But when visiting the opera house with more cultured friends, I should listen and ask more questions, rather than confidently assert my highly uninformed opinion.

Four main aspects of intellectual humility include being:

Intellectual humility is often hard work, especially when the stakes are high.

Starting with the admission that you, like everyone else, have cognitive biases and flaws that limit how much you know, intellectual humility might look like taking genuine interest in learning about your relative’s beliefs during a conversation at a family get-together, rather than waiting for them to finish so you can prove them wrong by sharing your – superior – opinion.

It could look like considering the merits of an alternative viewpoint on a hot-button political issue and why respectable, intelligent people might disagree with you. When you approach these challenging discussions with curiosity and humility, they become opportunities to learn and grow.

Though I’ve been studying humility for years, I’ve not yet mastered it personally. It’s hard to swim against cultural norms that reward being right and punish mistakes. It takes constant work to develop, but psychological science has documented numerous benefits.

First, there are social, cultural and technological advances to consider. Any significant breakthrough in medicine, technology or culture has come from someone admitting they didn’t know something – and then passionately pursuing knowledge with curiosity and humility. Progress requires admitting what you don’t know and seeking to learn something new.

Relationships improve when people are intellectually humble. Research has found that intellectual humility is associated with greater tolerance toward people with whom you disagree.

For example, intellectually humble people are more accepting of people who hold differing religious and political views. A central part of it is an openness to new ideas, so folks are less defensive to potentially challenging perspectives. They’re more likely to forgive, which can help repair and maintain relationships.

Finally, humility helps facilitate personal growth. Being intellectually humble allows you to have a more accurate view of yourself.

When you can admit and take ownership of your limitations, you can seek help in areas where you have room to grow, and you’re more responsive to information. When you limit yourself to only doing things the way you’ve always done them, you miss out on countless opportunities for growth, expansion and novelty – things that strike you with awe, fill you with wonder and make life worth living.

Humility can unlock authenticity and personal development.

Despite these benefits, sometimes humility gets a bad rap. People can have misconceptions about intellectual humility, so it’s important to dispel some myths.

Intellectual humility isn’t lacking conviction; you can believe something strongly until your mind is changed and you believe something else. It also isn’t being wishy-washy. You should have a high bar for what evidence you require to change your mind. It also doesn’t mean being self-deprecating or always agreeing with others. Remember, it’s being the right size, not too small.

Researchers are working hard to validate reliable ways to cultivate intellectual humility. I’m part of a team that is overseeing a set of projects designed to test different interventions to develop intellectual humility.

Some scholars are examining different ways to engage in discussions, and some are exploring the role of enhancing listening. Others are testing educational programs, and still others are looking at whether different kinds of feedback and exposure to diverse social networks might boost intellectual humility.

Prior work in this area suggests that humility can be cultivated, so we’re excited to see what emerges as the most promising avenues from this new endeavor.

There was one other thing that religion taught me that was slightly askew. I was told that too much learning could be ruinous; after all, you wouldn’t want to learn so much that you might lose your faith.

But in my experience, what I learned through loss may have salvaged a version of my faith that I can genuinely endorse and feels authentic to my experiences. The sooner we can open our minds and stop resisting change, the sooner we’ll find the freedom offered by humility.

Daryl Van Tongeren, Associate Professor of Psychology, Hope College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

Nothing more to add to this most interesting article.

We pass from 2023 into 2024.

So here we are, 2024, and the year when I become 80! However, I still have eleven months before that happens. Like an amazing number of people, I do not really think long about this New Year but there are plenty that do.

Here is an article that explains much more. It is from The Conversation.

ooOOoo

Rosalyn R. LaPier, University of Montana

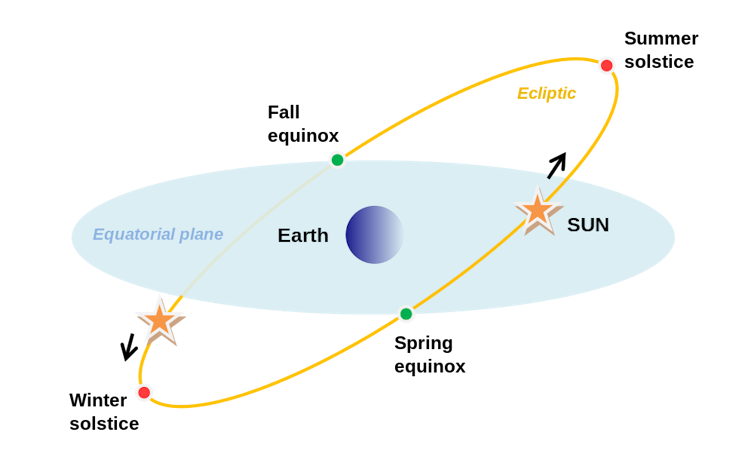

On the day of winter solstice, many Native American communities will hold religious ceremonies or community events.

The winter solstice is the day of the year when the Northern Hemisphere has the fewest hours of sunlight and the Southern Hemisphere has the most. For indigenous peoples, it has been a time to honor their ancient sun deity. They passed their knowledge down to successive generations through complex stories and ritual practices.

As a scholar of the environmental and Native American religion, I believe, there is much to learn from ancient religious practices.

For decades, scholars have studied the astronomical observations that ancient indigenous people made and sought to understand their meaning.

One such place was at Cahokia, near the Mississippi River in what is now Illinois across from St. Louis.

In Cahokia, indigenous people built numerous temple pyramids or mounds, similar to the structures built by the Aztecs in Mexico, over a thousand years ago. Among their constructions, what most stands out is an intriguing structure made up of wooden posts arranged in a circle, known today as “Woodhenge.”

To understand the purpose of Woodhenge, scientists watched the sun rise from this structure on winter solstice. What they found was telling: The sun aligned with both Woodhenge and the top of a temple mound – a temple built on top of a pyramid with a flat top – in the distance. They also found that the sun aligns with a different temple mound on summer solstice.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the people of Cahokia venerated the sun as a deity. Scholars believe that ancient indigenous societies observed the solar system carefully and wove that knowledge into their architecture.

Scientists have speculated that the Cahokia held rituals to honor the sun as a giver of life and for the new agricultural year.

Zuni Pueblo is a contemporary example of indigenous people with an agricultural society in western New Mexico. They grow corn, beans, squash, sunflowers and more. Each year they hold annual harvest festivals and numerous religious ceremonies, including at the winter solstice.

At the time of the winter solstice they hold a multiday celebration, known as the Shalako festival. The days for the celebration are selected by the religious leaders. The Zuni are intensely private, and most events are not for public viewing.

But what is shared with the public is near the end of the ceremony, when six Zuni men dress up and embody the spirit of giant bird deities. These men carry the Zuni prayers for rain “to all the corners of the earth.” The Zuni deities are believed to provide “blessings” and “balance” for the coming seasons and agricultural year.

As religion scholar Tisa Wenger writes, “The Zuni believe their ceremonies are necessary not just for the well-being of the tribe but for “the entire world.”

Not all indigenous peoples ritualized the winter solstice with a ceremony. But that doesn’t mean they didn’t find other ways to celebrate.

The Blackfeet tribe in Montana, where I am a member, historically kept a calendar of astronomical events. They marked the time of the winter solstice and the “return” of the sun or “Naatosi” on its annual journey. They also faced their tipis – or portable conical tents – east toward the rising sun.

They rarely held large religious gatherings in the winter. Instead the Blackfeet viewed the time of the winter solstice as a time for games and community dances. As a child, my grandmother enjoyed attending community dances at the time of the winter solstice. She remembered that each community held their own gatherings, with unique drumming, singing and dance styles.

Later, in my own research, I learned that the Blackfeet moved their dances and ceremonies during the early reservation years from times on their religious calendar to times acceptable to the U.S. government. The dances held at the time of the solstice were moved to Christmas Day or to New Year’s Eve.

Today, my family still spends the darkest days of winter playing card games and attending the local community dances, much like my grandmother did.

Although some winter solstice traditions have changed over time, they are still a reminder of indigenous peoples understanding of the intricate workings of the solar system. Or as the Zuni Pueblo’s rituals for all peoples of the earth demonstrate – of an ancient understanding of the interconnectedness of the world.

(This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.)

ooOOoo

Jean and I wish you all a Very Happy 2024. Please be safe and careful, and be happy!

I would not have believed this had I not read it with my own eyes.

I have been an atheist all my life. My mother and father were all those years ago when being an atheist was not something one promoted.

But a recent article from The Conversation told a very surprising account: “These spiritual caregivers can be found working in hospitals, universities, prisons and many other secular settings, serving people of all faiths and those with no faith tradition at all.“

Here’s the full article.

ooOOoo

Amy Lawton, Brandeis University

Published: September 7th, 2023

In times of loss, change or other challenges, chaplains can listen, provide comfort and discuss spiritual needs. These spiritual caregivers can be found working in hospitals, universities, prisons and many other secular settings, serving people of all faiths and those with no faith tradition at all.

Yet a common assumption is that chaplains themselves must be grounded in a religious tradition. After all, how can you be a religious leader without religion?

In reality, a growing number of chaplains are nonreligious: people who identify as atheist, agnostic, humanist or “spiritual but not religious.” I am a sociologist and research manager at Brandeis University’s Chaplaincy Innovation Lab, where our team researches and supports chaplains of all faiths, including those from nonreligious backgrounds. Our current research has focused on learning from 21 nonreligious chaplains about their experiences.

Thirty percent of Americans are religiously unaffiliated. Research suggests that people who are atheists or otherwise nonreligious sometimes reject a chaplain out of wariness, or shut down a conversation if they feel judged for their beliefs. But this research has not accounted for a new, increasingly likely situation – that the chaplain might also be nonreligious.

No national survey has been done, so the number of nonreligious chaplains is unknown. But there is plenty of reason to think that as more Americans choose not to affiliate with any particular religion, so too do more chaplains.

Nonreligious chaplains have been a part of hospital systems and universities for years, but they came into the national spotlight in August 2021 when Harvard University’s organization of chaplains unanimously elected humanist and atheist Greg Epstein as president. Humanists believe in the potential and goodness of human beings without reference to the supernatural.

Other recent reporting on humanist chaplains has also focused on school campuses, but nonreligious chaplains are not limited to colleges and universities. Eighteen of the 21 nonreligious chaplains we spoke with in our study work in health care, including hospice. The Federal Bureau of Prisons allows nonreligious chaplains, but we were unable to find any of them to participate in the current study.

Not all settings allow nonreligious chaplains, however, including the U.S. military.

The idea of a “call” from God is central to many religious vocations: a strong impulse toward religious leadership, which many people attribute to the divine.

Chaplains who are atheists, agnostics, humanists or who consider themselves spiritual but not religious also can feel called. But they do not believe that their calls come from a deity.

Joe, for example, an atheist and a humanist whom we interviewed, has worked as a chaplain in hospitals and hospices. He says that his “light bulb moment” came after a history professor told him that beliefs are the source of a community’s power. While atheists do not believe in God or gods, many do have strong beliefs about ethics and morality, and American atheists are more likely than American Christians to say they often feel a sense of wonder about the universe. Joe’s call was not “from a divine source,” but nonetheless, he says this experience “kind of filled me with a sense of control, and confidence, and presence” in his life that grounded his sense of a calling.

Sunil, another chaplain our team interviewed, was inspired by his college chaplain, whom he calls “a really influential presence.” The chaplain helped Sunil answer questions about identity and values without “necessarily having any religious or spiritual leanings to it,” and encouraged him to go to divinity school.

Today, Sunil tries to help others answer those same questions in his work as a health care chaplain – and to offer deeply thoughtful, meaningful spiritual care to people who aren’t religious.

Most chaplaincy jobs require a theological degree. Along with coursework in sacred scriptures and religious leadership, chaplaincy training usually involves clinical pastoral education, where students learn about hands-on, care-oriented aspects of their profession. This involves learning to provide care to everyone, regardless of their religious background.

Although coursework is broadly the same for all students, religious or nonreligious, the actual experience of earning a degree is very different for nonreligious students. In the United States, Christian students are easily able to enroll in a seminary or divinity school that shares their faith identity and spend their years of study learning about their own tradition.

Chaplaincy programs that focus on non-Christian traditions are available, but scarcer, and our team does not know of an overtly nonreligious chaplaincy program. In recent years, more seminaries have welcomed nonreligious students, but nonetheless, nonreligious students often find themselves focusing their study on traditions to which they have no personal connection.

Yet there is a surprising bright side.

Being deeply immersed in traditions that are not one’s own is one of the reasons that nonreligious chaplains can be so effective.

For example, our team asked Kathy, a health care chaplain, how she approaches prayer with religious and nonreligious patients. “My goal is to try to meet that person where they are and pray in a way that’s helpful and comforting for them, or meets whatever the need is that’s arisen during the conversation that we’ve had,” she said. Like all chaplains, Kathy is there to accompany, not proselytize. While she herself prays to the “great mystery,” she is comfortable facilitating whatever prayer is needed.

Claire, a chaplaincy student, agreed with Kathy and described her own first experience meeting an evangelical Christian patient. It was easy, she said, because “you’re not trying to fix anything. You’re just trying to meet them where they are. So that’s it.”

Nonreligious chaplains are used to thinking outside the box. Having learned about major world religions, many of them can find overlapping values and beliefs with their patients, such as finding beauty and meaning in the natural world or finding strength in their conviction that human beings are inherently good.

Cynthia works in the palliative care department in a hospital and tells her patients, “I am here to support you in whatever is meaningful to you right now and whatever is most important in your life in this moment.” She asks patients: “What are you struggling with right now? What are your goals? What do you hope for? What are you afraid of?” – trying to “unpack that with a spiritual lens rather than a medical lens.”

Cynthia is an example of why spiritual care by nonreligious chaplains may be surprising, but is likely here to stay. Based on our research, nonreligious chaplains are as capable as religious chaplains of meeting a person in their darkest hour and taking them by the hand.

Amy Lawton, Research Manager, Chaplaincy Innovation Lab, Brandeis University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

That last sentence may be opened up even more. In that the article speaks of chaplains, both religious and nonreligious. But as someone who was a counsellor with the Prince’s Youth Business Trust some years ago, now The Prince’s Trust, it is my opinion that anyone who is an active listener can undertake the role.

The article has many fine points including one that I had not considered before. “That American atheists are more likely than American Christians to say they often feel a sense of wonder about the universe.” I am certain that this isn’t confined to Americans.

It goes back much further than the Christian church.

Jean and I are atheists and have been all our lives. Therefore we tend to take more notice of the Winter solstice (that is today as the day that I am preparing this post) rather than Christmas Day and our sense that it is a product of Jesus Christ being born on the 25th; or so I thought!

But the tradition of a Christmas tree in particular goes much further back, as this article from The Conversation sets out.

ooOOoo

Troy Bickham, Texas A&M University

Why, every Christmas, do so many people endure the mess of dried pine needles, the risk of a fire hazard and impossibly tangled strings of lights?

Strapping a fir tree to the hood of my car and worrying about the strength of the twine, I sometimes wonder if I should just buy an artificial tree and do away with all the hassle. Then my inner historian scolds me – I have to remind myself that I’m taking part in one of the world’s oldest religious traditions. To give up the tree would be to give up a ritual that predates Christmas itself.

Almost all agrarian societies independently venerated the Sun in their pantheon of gods at one time or another – there was the Sol of the Norse, the Aztec Huitzilopochtli, the Greek Helios.

The solstices, when the Sun is at its highest and lowest points in the sky, were major events. The winter solstice, when the sky is its darkest, has been a notable day of celebration in agrarian societies throughout human history. The Persian Shab-e Yalda, Dongzhi in China and the North American Hopi Soyal all independently mark the occasion.

The favored décor for ancient winter solstices? Evergreen plants.

Whether as palm branches gathered in Egypt in the celebration of Ra or wreaths for the Roman feast of Saturnalia, evergreens have long served as symbols of the perseverance of life during the bleakness of winter, and the promise of the Sun’s return.

Christmas came much later. The date was not fixed on liturgical calendars until centuries after Jesus’ birth, and the English word Christmas – an abbreviation of “Christ’s Mass” – would not appear until over 1,000 years after the original event.

While Dec. 25 was ostensibly a Christian holiday, many Europeans simply carried over traditions from winter solstice celebrations, which were notoriously raucous affairs. For example, the 12 days of Christmas commemorated in the popular carol actually originated in ancient Germanic Yule celebrations.

The continued use of evergreens, most notably the Christmas tree, is the most visible remnant of those ancient solstice celebrations. Although Ernst Anschütz’s well-known 1824 carol dedicated to the tree is translated into English as “O Christmas Tree,” the title of the original German tune is simply “Tannenbaum,” meaning fir tree. There is no reference to Christmas in the carol, which Anschütz based on a much older Silesian folk love song. In keeping with old solstice celebrations, the song praises the tree’s faithful hardiness during the dark and cold winter.

Sixteenth-century German Protestants, eager to remove the iconography and relics of the Roman Catholic Church, gave the Christmas tree a huge boost when they used it to replace Nativity scenes. The religious reformer Martin Luther supposedly adopted the practice and added candles.

But a century later, the English Puritans frowned upon the disorderly holiday for lacking biblical legitimacy. They banned it in the 1650s, with soldiers patrolling London’s streets looking for anyone daring to celebrate the day. Puritan colonists in Massachusetts did the same, fining “whosoever shall be found observing Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way.”

German immigration to the American colonies ensured that the practice of trees would take root in the New World. Benjamin Franklin estimated that at least one-third of Pennsylvania’s white population was German before the American Revolution.

Yet, the German tradition of the Christmas tree blossomed in the United States largely due to Britain’s German royal lineage.

Since 1701, English kings had been forbidden from becoming or marrying Catholics. Germany, which was made up of a patchwork of kingdoms, had eligible Protestant princes and princesses to spare. Many British royals privately maintained the familiar custom of a Christmas tree, but Queen Victoria – who had a German mother as well as a German grandmother on her father’s side – made the practice public and fashionable.

Victoria’s style of rule both reflected and shaped the outwardly stern, family-centered morality that dominated middle-class life during the era. In the 1840s, Christmas became the target of reformers like novelist Charles Dickens, who sought to transform the raucous celebrations of the largely sidelined holiday into a family day in which the people of the rapidly industrialized nation could relax, rejoice and give thanks.

His 1843 novella, “A Christmas Carol,” in which the miserly Ebenezer Scrooge found redemption by embracing Dickens’ prescriptions for the holiday, was a hit with the public. While the evergreen décor is evident in the hand-colored illustrations Dickens specially commissioned for the book, there are no Christmas trees in those pictures.

Victoria added the fir tree to family celebrations five years later. Although Christmas trees had been part of private royal celebrations for decades, an 1848 issue of the London Illustrated News depicted Victoria with her German husband and children decorating one as a family at Windsor Castle.

The cultural impact was almost instantaneous. Christmas trees started appearing in homes throughout England, its colonies and the rest of the English-speaking world. Dickens followed with his short story “A Christmas Tree” two years later.

During this period, America’s middle classes generally embraced all things Victorian, from architecture to moral reform societies.

Sarah Hale, the author most famous for her children’s poem “Mary had a Little Lamb,” used her position as editor of the best-selling magazine Godey’s Ladies Book to advance a reformist agenda that included the abolition of slavery and the creation of holidays that promoted pious family values. The adoption of Thanksgiving as a national holiday in 1863 was perhaps her most lasting achievement.

It is closely followed by the Christmas tree.

While trees sporadically adorned the homes of German immigrants in the U.S., it became a mainstream middle-class practice when, in 1850, Godey’s published an engraving of Victoria and her Christmas tree. A supporter of Dickens and the movement to reinvent Christmas, Hale helped to popularize the family Christmas tree across the pond.

Only in 1870 did the United States recognize Christmas as a federal holiday.

The practice of erecting public Christmas trees emerged in the U.S. in the 20th century. In 1923, the first one appeared on the White House’s South Lawn. During the Great Depression, famous sites such as New York’s Rockefeller Center began erecting increasingly larger trees.

As both American and British cultures extended their influence around the world, Christmas trees started to appear in communal spaces even in countries that are not predominately Christian. Shopping districts in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Hong Kong and Tokyo now regularly erect trees.

The modern Christmas tree is a universal symbol that carries meanings both religious and secular. Adorned with lights, they promote hope and offer brightness in literally the darkest time of year for half of the world.

In that sense, the modern Christmas tree has come full circle.

Troy Bickham, Professor of History, Texas A&M University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

So not a doggie post for today but nevertheless one that I hope will be of interest.

The next post will be a Picture Parade this coming Sunday: December 25th!

It just seemed too soon to continue another Picture Parade!

So I chose this video. It is short but conveys the essence of the late Queen Elizabeth II.