The more we give up, the more we ‘own’.

It is a very common, understandable trait of us humans to put our own lives first. I mean that much more in the psychological sense than in the sense of our daily activities although what we think and feel, inevitably, influences how we behave. One of the fabulous qualities of our dogs is that they are so much more sensitive to the world around them than to their own internal thoughts and feelings. Right from the early years of having Pharaoh in my life I was aware that he ‘read’ my emotions easily and soon became an instinctive ‘friend’, especially when I was troubled.

Years later, all of the dogs love it when Jean and I are in happy, positive places and you can see how our human states of mind link so directly to the mood of our dogs.

All of which is my introduction to an essay recently read over on the Big Think blogsite. Specifically, one about living empathically. The essay is called: Let’s Make 2015 “The Year of Living Empathetically” and here are the opening paragraphs:

Let’s Make 2015 “The Year of Living Empathetically”

I began the new year on a very positive – and inspiring – note after reading Eric Liu’s latest commentary on “Radical Empathy”.

The founder and CEO of Citizen University, Liu shows us that laying aside our egos – our need to be in the right – in favor of standing in the shoes of others, is key to addressing so many of the problems that we (once again) confronted in 2014.

This insight – without question – is a wake-up call to our country as 2015 unfolds.

That’s why I think we should resolve to make 2015 “The Year of Living Empathetically.”

We need to make the practice of empathy our New Year’s exercise regimen, our social-emotional diet for the next 365 days.

- Let’s practice empathy at home, with our spouses and kids.

- Let’s practice empathy in the workplace, as we give and receive feedback, and credit others’ contributions generously.

- Let’s practice empathy in the classroom, especially when kids are struggling and need our support.

- Let’s practice empathy in public service, as we encounter people who look different from us, and whose lives matter every bit as much as our own.

- Let’s practice empathy as we encounter people on the street, who may be less fortunate, and are just as human.

- Let’s practice empathy when resolving conflict, whether interpersonally or on a global-political level.

- And let’s practice empathy in local and state governments, and in the halls of Congress, so that we might truly listen in order to solve real problems

If all this sounds like a tall order – you’re right; it is.

As Brene Brown, a research professor at the University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work, points out, empathy is a challenging personal choice that requires us to become vulnerable in an effort to connect with another person.

It is not a long essay, so do drop across to here and finish reading it.

As is the way of ideas, serendipity is always actively working ‘under the hood’.

Why do I say that?

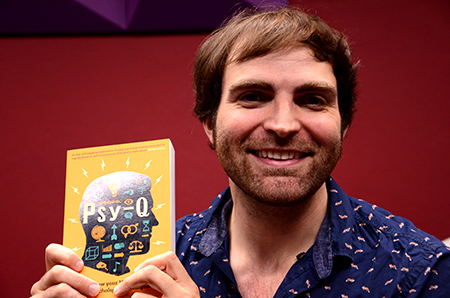

Because as soon as I was clear about what I wanted to offer you for today, in to my ‘in-box’ came the latest TED Talk. A talk from Ben Ambridge entitled: 10 myths about psychology: Debunked. It so resonated with today’s theme and is offered below.

Published on Feb 4, 2015

How much of what you think about your brain is actually wrong? In this whistlestop tour of dis-proved science, Ben Ambridge walks through 10 popular ideas about psychology that have been proven wrong — and uncovers a few surprising truths about how our brains really work.Ben Ambridge is the author of “Psy-Q,” a sparkling book debunking what we think we know about psychology.

Why you should listen?

Ben Ambridge is a senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Liverpool, where he researches children’s language development. He is the author of Psy-Q, which introduces readers to some of the major findings in psychology via interactive puzzles, games, quizzes and tests.

He also writes great newsy stories connecting psychology to current events. His article “Why Can’t We Talk to the Animals?” was shortlisted for the 2012 Guardian-Wellcome Science Writing Prize. Psy-Q is his first book for a general audience.

If you want to learn more about the good Professor, here is his webpage on the University of Liverpool‘s website. And here is Ben Ambridge’s personal webpage that lists many, if not all, of his publications.

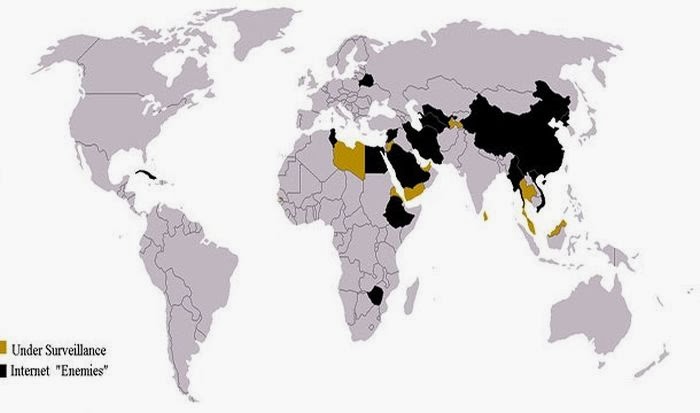

I honestly can’t find a better picture to close today’s post about sensitivity and empathy than this one below: