This time it is dogs sleeping, courtesy of Unsplash.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

It really is amazing how and where dogs go to sleep!

Thank you, Unsplash!

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Category: Dogs

This time it is dogs sleeping, courtesy of Unsplash.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

It really is amazing how and where dogs go to sleep!

Thank you, Unsplash!

Yet more dog photos courtesy of Unsplash!

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

My same feeling as last Sunday! Dogs are perfect.

Last Picture Parade for September, 2025.

Again, the photos are downloaded from Unsplash.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

Wonderful, beautiful animals!

🐶❤️ Because the love of a dog changes your day.

Thank you, John.

A terrific set of videos!

John Zande sent me an email yesterday. It contained a link that when clicked on took me to a series of videos.

Here is the first one I looked at:

That link sent by John is here: https://www.youtube.com/@BarkBondOfc

Back to dogs; this time dogs being trained.

Still with Unsplash. And apologies for any duplications.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

More photographs in a week’s time.

From the find of the six puppies to the fantastic conclusion.

I subscribe to The Dodo. On September 5th Maeve Dunigan wrote an article that is so beautiful. I have permission to republish the story.

ooOOoo

Rescuers Hear Cries In Open Field — Then See Faces Peeking Out Of A Drain.

“[They] were friendly and very social.”

Published on Sep 5, 2025

In a field near the Kansas Humane Society’s Murfin Animal Care Campus, a concrete storm drain peeks out of the green grass, its circular opening extending into a black tunnel below. One morning this past July, humane society team members arrived at work and heard a heartbreaking sound echoing from within this drain — the sound of animals crying for help.

The rescuers hurried over and found the source of the noise. There, cowering inside, were six little puppies left to fend for themselves.

Using treats as a tasty incentive, the team coaxed each puppy out from the hole. The pups served a mandatory stray hold at the Wichita Animal Shelter next door. Then they returned to the Kansas Humane Society for further care.

Staff members gave the pups a comfortable place to recover. They named the dogs Abby, Ellie, Greg, Lev, Mike and Tommy, and made sure each of them received the necessary vaccines and medical attention needed to grow up healthy and strong.

“The puppies were very wiggly, especially Ellie,” a representative from Kansas Humane Society told The Dodo. “All were friendly and very social.”

Local news stations soon began covering the amazing rescue, urging community members to adopt or foster the pups. Within two days, every puppy was either adopted or put on hold for adoption.

Today, Abby, Ellie, Greg, Lev, Mike and Tommy are all safe in their forever homes, and rescuers couldn’t be happier.

“We hope their futures are full of love, cuddles and treats,” the representative said.

To help other animals like these puppies, you can make a donation to the Kansas Humane Society.

ooOOoo

It is stories like this one that provide the incentive for not engaging in politics. Period!

She has her own doorbell.

A lovely video.

Emmy’s way of seeing her ‘Mum’, namely Linda Rose.

ooOOoo

Jean and I are atheists. I subscribe to the American Humanist Association whose motto is “GOOD WITHOUT A GOD”.

Bill Watterson of the AHA posted the following yesterday:

I wish people were more like animals. Animals don’t try to change you. Animals like you just the way you are. They listen to your problems, they comfort you when you’re sad, and all they ask in return is a little kindness.

So, so true!

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

There are few people visiting Learning from Dogs these days but so what! I do not publish posts to elicit comments or ‘Likes’, I just do it for my own pleasure, and if there are a very few who like my blog posts then that is a bonus.

Plus I cannot guarantee that some of these photographs have not appeared in earlier Picture Parades.

It is what we share with animals, but it is not as straightforward as one thinks!

The range of thinking, in terms of logical thinking, even in humans, is enormous. And when we watch animals, especially mammals, it is clear that they are operating in a logical manner. By ‘operating’ I am referring to their thought processes.

So a recent article in The Conversation jumped out at me. Here it is:

ooOOoo

Olga Lazareva, Drake University

Can a monkey, a pigeon or a fish reason like a person? It’s a question scientists have been testing in increasingly creative ways – and what we’ve found so far paints a more complicated picture than you’d think.

Imagine you’re filling out a March Madness bracket. You hear that Team A beat Team B, and Team B beat Team C – so you assume Team A is probably better than Team C. That’s a kind of logical reasoning known as transitive inference. It’s so automatic that you barely notice you’re doing it.

It turns out humans are not the only ones who can make these kinds of mental leaps. In labs around the world, researchers have tested many animals, from primates to birds to insects, on tasks designed to probe transitive inference, and most pass with flying colors.

As a scientist focused on animal learning and behavior, I work with pigeons to understand how they make sense of relationships, patterns and rules. In other words, I study the minds of animals that will never fill out a March Madness bracket – but might still be able to guess the winner.

The basic idea is simple: If an animal learns that A is better than B, and B is better than C, can it figure out that A is better than C – even though it’s never seen A and C together?

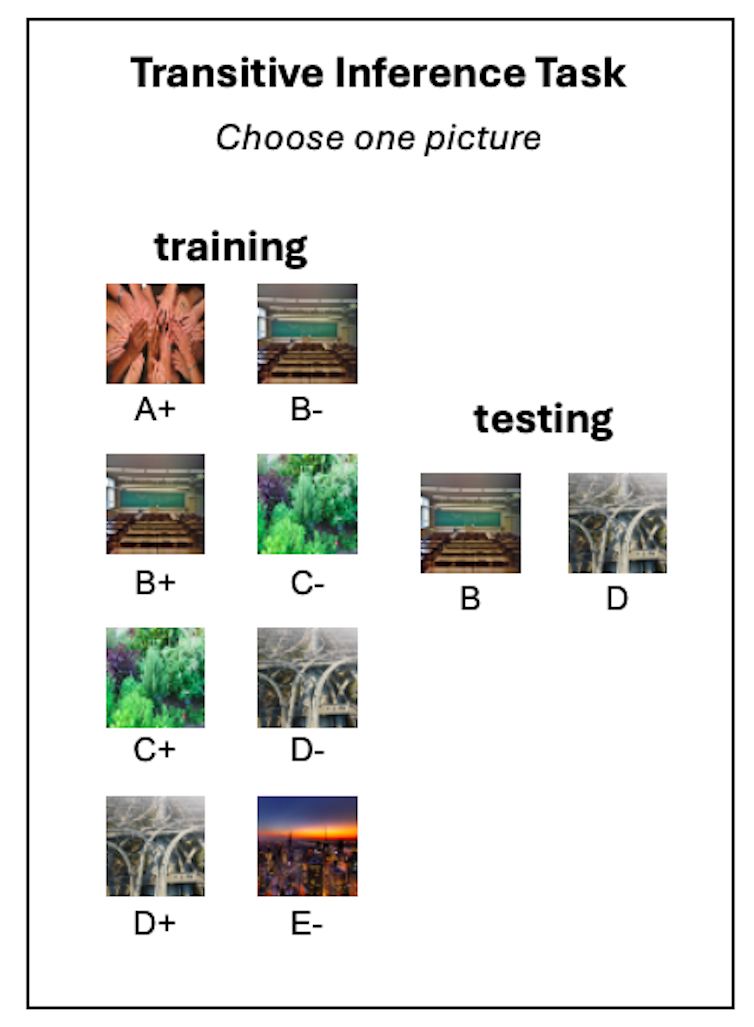

In the lab, researchers test this by giving animals randomly paired images, one pair at a time, and rewarding them with food for picking the correct one. For example, animals learn that a photo of hands (A) is correct when paired with a classroom (B), a classroom (B) is correct when paired with bushes (C), bushes (C) are correct when paired with a highway (D), and a highway (D) is correct when paired with a sunset (E). We don’t know whether they “understand” what’s in the picture, and it is not particularly important for the experiment that they do.

One possible explanation is that the animals that learn all the tasks create a mental ranking of these images: A > B > C > D > E. We test this idea by giving them new pairs they’ve never seen before, such as classroom (B) vs. highway (D). If they consistently pick the higher-ranked item, they’ve inferred the underlying order.

What’s fascinating is how many species succeed at this task. Monkeys, rats, pigeons – even fish and wasps – have all demonstrated transitive inference in one form or another.

But not all types of reasoning come so easily. There’s another kind of rule called transitivity that is different from transitive inference, despite the similar name. Instead of asking which picture is better, transitivity is about equivalence.

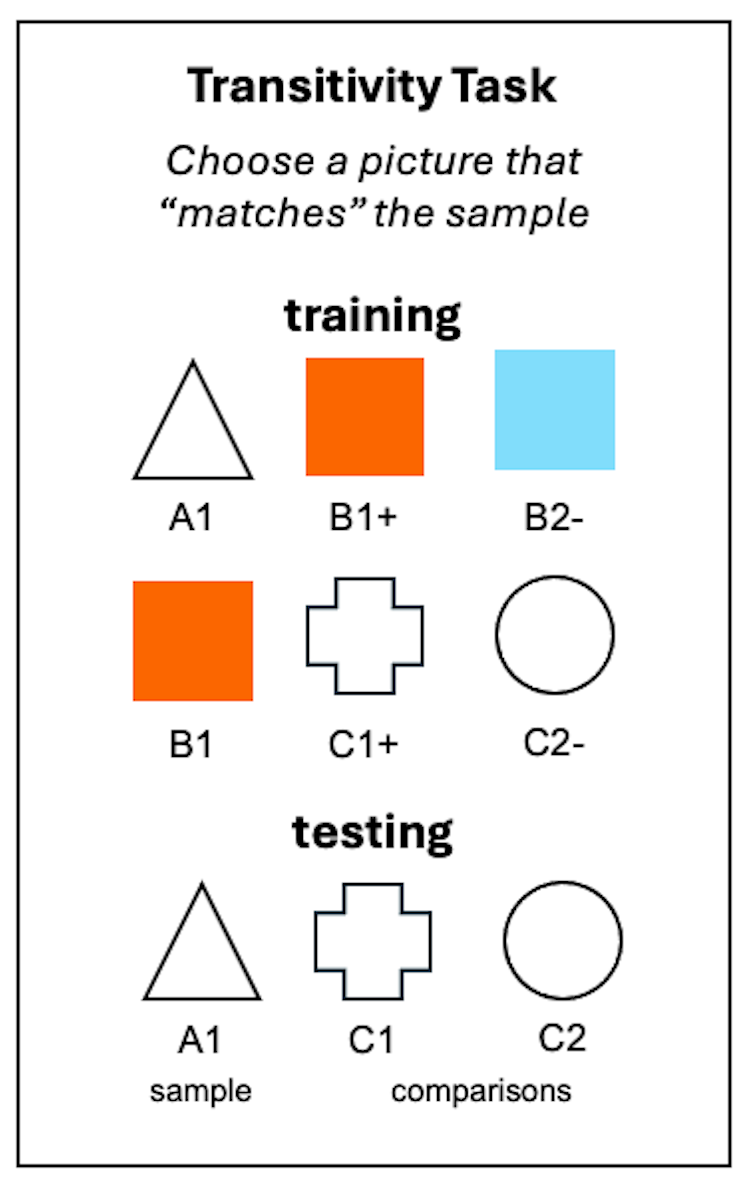

In this task, animals are shown a set of three pictures and asked which one goes with the center image. For example, if white triangle (A1) is shown, choosing red square (B1) earns a reward, while choosing blue square (B2) does not. Later, when red square (B1) is shown, choosing white cross (C1) earns a reward while choosing white circle (C2) does not. Now comes the test: white triangle (A1) is shown with white cross (C1) and white circle (C2) as choices. If they pick white cross (C1), then they’ve demonstrated transitivity.

The change may seem small, but species that succeed in those first transitive inference tasks often stumble in this task. In fact, they tend to treat the white triangle and the white cross as completely separate things, despite their common relationship with the red square. In my recently published review of research using the two tasks, I concluded that more evidence is needed to determine whether these tests tap into the same cognitive ability.

Why does the difference between transitive inference and transitivity matter? At first glance, they may seem like two versions of the same ability – logical reasoning. But when animals succeed at one and struggle with the other, it raises an important question: Are these tasks measuring the same kind of thinking?

The apparent difference between the two tasks isn’t just a quirk of animal behavior. Psychology researchers apply these tasks to humans in order to draw conclusions about how people reason.

For example, say you’re trying to pick a new almond milk. You know that Brand A is creamier than Brand B, and your friend told you that Brand C is even waterier than Brand B. Based on that, because you like a thicker milk, you might assume Brand A is better than Brand C, an example of transitive inference.

But now imagine the store labels both Brand A and Brand C as “barista blends.” Even without tasting them, you might treat them as functionally equivalent, because they belong to the same category. That’s more like transitivity, where items are grouped based on shared relationships. In this case, “barista blend” signals the brands share similar quality.

Researchers often treat these types of reasoning as measuring the same ability. But if they rely on different mental processes, they might not be interchangeable. In other words, the way scientists ask their questions may shape the answer – and that has big implications for how they interpret success in animals and in people.

This difference could affect how researchers interpret decision-making not only in the lab, but also in everyday choices and in clinical settings. Tasks like these are sometimes used in research on autism, brain injury or age-related cognitive decline.

If two tasks look similar on the surface, then choosing the wrong one might lead to inaccurate conclusions about someone’s cognitive abilities. That’s why ongoing work in my lab is exploring whether the same distinction between these logical processes holds true for people.

Just like a March Madness bracket doesn’t always predict the winner, a reasoning task doesn’t always show how someone got to the right answer. That’s the puzzle researchers are still working on – figuring out whether different tasks really tap into the same kind of thinking or just look like they do. It’s what keeps scientists like me in the lab, asking questions, running experiments and trying to understand what it really means to reason – no matter who’s doing the thinking.

Olga Lazareva, Professor of Psychology, Drake University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

Fascinating! I quote: “… a reasoning task doesn’t always show how someone got to the right answer.“

Olga finishes her article on reasoning with the statement that scientists are still trying to understand what it means to reason!