Taken from The Dodo! Enjoy!

Just a small piece of fun

Taken from The Dodo! Enjoy!

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Category: Communication

Taken from The Dodo! Enjoy!

Like any new start-up of a business venture, this requires knowledge, skills and quite a bit of luck!

I am delighted to offer this guest post by Penny.

ooOOoo

Image: Freepik

Vision to Reality: Building a Profitable Vet Clinic

Launching a veterinary clinic is a significant endeavor that requires meticulous planning and strategic decision-making. This venture combines a passion for animal care with the intricacies of managing a successful business. Aspiring clinic owners must navigate several critical steps to lay a strong foundation and ensure operational excellence. Starting your own clinic promises not only to fulfill a dream of helping animals but also to establish a thriving enterprise in the community.

Build a Strong Foundation with an Effective Marketing Strategy

A robust marketing strategy is essential to attract potential clients in the digital era. Establishing a professional online presence through a user-friendly website that details your services, team, and location builds trust among pet owners. Engage actively on social media with regular updates and client testimonials to showcase your expertise and commitment to animal care. Forge partnerships with local pet-related businesses to increase visibility and drive traffic to your clinic, enhancing both your and your partners’ customer bases.

Craft a Clear and Detailed Business Plan

A well-constructed business plan acts as your clinic’s roadmap, detailing your mission, services offered, and the specific target market. Identify your niche early—whether it’s specializing in certain animals or treatments—to attract the appropriate clientele. Include comprehensive financial projections and a marketing budget in your plan to ensure financial preparedness and support your clinic’s promotional activities.

Enhance Your Business Knowledge by Pursuing an MBA

Running a veterinary clinic demands a blend of clinical and business expertise. Pursuing a master’s of business administration online can boost your proficiency in key business areas such as strategy, management, and finance. An MBA not only deepens your understanding of business operations but also enhances leadership skills and self-assessment capabilities. These competencies are essential for balancing the medical and business demands of your clinic, ensuring its long-term success.

Safeguard Your Business with Proper Insurance

Operating a veterinary clinic comes with inherent risks, making comprehensive insurance coverage essential. Essential policies include malpractice insurance to handle legal issues and general liability insurance for accidents on your premises. Property insurance is crucial to protect your clinic’s infrastructure and equipment against unexpected events. Consulting with an insurance expert can ensure that you have thorough coverage to protect against potential financial setbacks.

Invest in High-Quality Veterinary Equipment

Providing top-tier care necessitates investing in high-quality veterinary equipment. Essential tools like X-ray machines, surgical instruments, and lab equipment should be of the highest standard to ensure accurate diagnoses and treatments. Modern technologies, such as digital imaging systems, not only enhance patient care but also improve operational efficiency. While the initial cost may be higher, investing in quality equipment pays off in the long run by boosting efficiency and minimizing errors.

Secure the Necessary Funding for Your Clinic

Securing sufficient funding is critical when starting a veterinary clinic. Estimate your startup costs accurately to understand your financial needs, including equipment, premises, staffing, and marketing. Explore diverse financing options, such as bank loans, private investors, and specialty medical practice loans that might offer favorable terms. Adequate initial funding prevents cash flow problems and supports your clinic’s growth trajectory.

Choose the Right Location for Your Clinic

The location of your clinic is pivotal to its success, necessitating a spot with a high demand for veterinary services. Conduct thorough market research to choose a community rich in pet owners who need your services. Select a location that is accessible, visible, and has ample parking to ensure convenience for your clients. Proximity to complementary services like pet groomers or dog trainers can further enhance client traffic and provide expansion opportunities.

Opening a veterinary clinic is both challenging and rewarding, demanding a careful blend of dedication and strategic foresight. Success in this field not only enhances the well-being of pets but also contributes positively to the local community. It requires ongoing commitment to adapt and grow in a dynamic environment. Ultimately, the fulfillment of running a successful veterinary clinic comes from both the impact on animal health and the achievement of entrepreneurial goals.

Discover the timeless wisdom that dogs offer at Learning from Dogs, where integrity and living in the present are celebrated. Dive into our content and embrace the lessons from our four-legged friends.

ooOOoo

This is a skilled summary of the needs of opening a vet’s clinic. And thank you, Penny, for your last paragraph. It has been a pleasure!

Here is one explanation.

There is no question the world’s weather systems are changing. However, for folk who are not trained in this science it is all a bit mysterious. So thank goodness that The Conversation have not only got a scientist who does know what he is talking about but also they are very happy for it to be republished.

ooOOoo

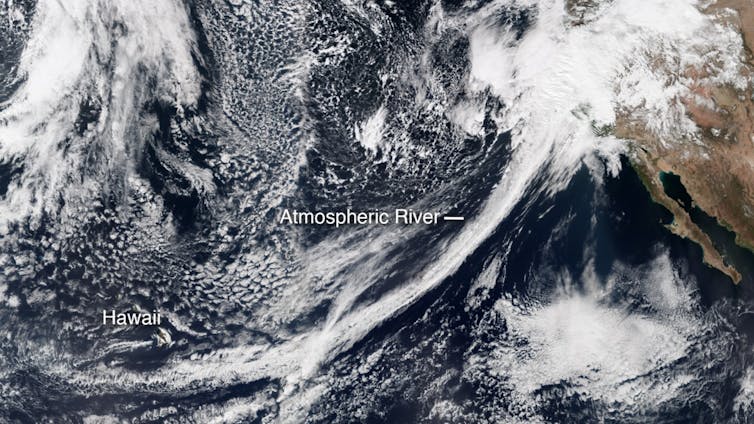

Zhe Li, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

Atmospheric rivers – those long, narrow bands of water vapor in the sky that bring heavy rain and storms to the U.S. West Coast and many other regions – are shifting toward higher latitudes, and that’s changing weather patterns around the world.

The shift is worsening droughts in some regions, intensifying flooding in others, and putting water resources that many communities rely on at risk. When atmospheric rivers reach far northward into the Arctic, they can also melt sea ice, affecting the global climate.

In a new study published in Science Advances, University of California, Santa Barbara, climate scientist Qinghua Ding and I show that atmospheric rivers have shifted about 6 to 10 degrees toward the two poles over the past four decades.

Atmospheric rivers aren’t just a U.S West Coast thing. They form in many parts of the world and provide over half of the mean annual runoff in these regions, including the U.S. Southeast coasts and West Coast, Southeast Asia, New Zealand, northern Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom and south-central Chile.

California relies on atmospheric rivers for up to 50% of its yearly rainfall. A series of winter atmospheric rivers there can bring enough rain and snow to end a drought, as parts of the region saw in 2023.

While atmospheric rivers share a similar origin – moisture supply from the tropics – atmospheric instability of the jet stream allows them to curve poleward in different ways. No two atmospheric rivers are exactly alike.

What particularly interests climate scientists, including us, is the collective behavior of atmospheric rivers. Atmospheric rivers are commonly seen in the extratropics, a region between the latitudes of 30 and 50 degrees in both hemispheres that includes most of the continental U.S., southern Australia and Chile.

Our study shows that atmospheric rivers have been shifting poleward over the past four decades. In both hemispheres, activity has increased along 50 degrees north and 50 degrees south, while it has decreased along 30 degrees north and 30 degrees south since 1979. In North America, that means more atmospheric rivers drenching British Columbia and Alaska.

One main reason for this shift is changes in sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific. Since 2000, waters in the eastern tropical Pacific have had a cooling tendency, which affects atmospheric circulation worldwide. This cooling, often associated with La Niña conditions, pushes atmospheric rivers toward the poles.

The poleward movement of atmospheric rivers can be explained as a chain of interconnected processes.

During La Niña conditions, when sea surface temperatures cool in the eastern tropical Pacific, the Walker circulation – giant loops of air that affect precipitation as they rise and fall over different parts of the tropics – strengthens over the western Pacific. This stronger circulation causes the tropical rainfall belt to expand. The expanded tropical rainfall, combined with changes in atmospheric eddy patterns, results in high-pressure anomalies and wind patterns that steer atmospheric rivers farther poleward.

Conversely, during El Niño conditions, with warmer sea surface temperatures, the mechanism operates in the opposite direction, shifting atmospheric rivers so they don’t travel as far from the equator.

The shifts raise important questions about how climate models predict future changes in atmospheric rivers. Current models might underestimate natural variability, such as changes in the tropical Pacific, which can significantly affect atmospheric rivers. Understanding this connection can help forecasters make better predictions about future rainfall patterns and water availability.

A shift in atmospheric rivers can have big effects on local climates.

In the subtropics, where atmospheric rivers are becoming less common, the result could be longer droughts and less water. Many areas, such as California and southern Brazil, depend on atmospheric rivers for rainfall to fill reservoirs and support farming. Without this moisture, these areas could face more water shortages, putting stress on communities, farms and ecosystems.

In higher latitudes, atmospheric rivers moving poleward could lead to more extreme rainfall, flooding and landslides in places such as the U.S. Pacific Northwest, Europe, and even in polar regions.

In the Arctic, more atmospheric rivers could speed up sea ice melting, adding to global warming and affecting animals that rely on the ice. An earlier study I was involved in found that the trend in summertime atmospheric river activity may contribute 36% of the increasing trend in summer moisture over the entire Arctic since 1979.

So far, the shifts we have seen still mainly reflect changes due to natural processes, but human-induced global warming also plays a role. Global warming is expected to increase the overall frequency and intensity of atmospheric rivers because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture.

How that might change as the planet continues to warm is less clear. Predicting future changes remains uncertain due largely to the difficulty in predicting the natural swings between El Niño and La Niña, which play an important role in atmospheric river shifts.

As the world gets warmer, atmospheric rivers – and the critical rains they bring – will keep changing course. We need to understand and adapt to these changes so communities can keep thriving in a changing climate.

Zhe Li, Postdoctoral Researcher in Earth System Science, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

Those last two paragraphs of the above article show the difficulty in coming up with clear predictions of the future. As was said: ‘How that might change as the planet continues to warm is less clear. Predicting future changes remains uncertain due largely to the difficulty in predicting the natural swings between El Niño and La Niña, which play an important role in atmospheric river shifts.‘

This attracted me very much, and I wanted to share it with you.

The opening paragraph of this article caught my eye so I read it fully. As it was published in The Conversation then that meant I could republish it.

ooOOoo

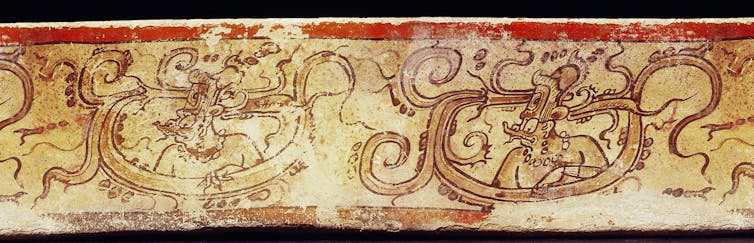

James L. Fitzsimmons, Middlebury

The ancient Maya believed that everything in the universe, from the natural world to everyday experiences, was part of a single, powerful spiritual force. They were not polytheists who worshipped distinct gods but pantheists who believed that various gods were just manifestations of that force.

Some of the best evidence for this comes from the behavior of two of the most powerful beings of the Maya world: The first is a creator god whose name is still spoken by millions of people every fall – Huracán, or “Hurricane.” The second is a god of lightning, K’awiil, from the early first millennium C.E.

As a scholar of the Indigenous religions of the Americas, I recognize that these beings, though separated by over 1,000 years, are related and can teach us something about our relationship to the natural world.

Huracán was once a god of the K’iche’, one of the Maya peoples who today live in the southern highlands of Guatemala. He was one of the main characters of the Popol Vuh, a religious text from the 16th century. His name probably originated in the Caribbean, where other cultures used it to describe the destructive power of storms.

The K’iche’ associated Huracán, which means “one leg” in the K’iche’ language, with weather. He was also their primary god of creation and was responsible for all life on earth, including humans.

Because of this, he was sometimes known as U K’ux K’aj, or “Heart of Sky.” In the K’iche’ language, k’ux was not only the heart but also the spark of life, the source of all thought and imagination.

Yet, Huracán was not perfect. He made mistakes and occasionally destroyed his creations. He was also a jealous god who damaged humans so they would not be his equal. In one such episode, he is believed to have clouded their vision, thus preventing them from being able to see the universe as he saw it.

Huracán was one being who existed as three distinct persons: Thunderbolt Huracán, Youngest Thunderbolt and Sudden Thunderbolt. Each of them embodied different types of lightning, ranging from enormous bolts to small or sudden flashes of light.

Despite the fact that he was a god of lightning, there were no strict boundaries between his powers and the powers of other gods. Any of them might wield lightning, or create humanity, or destroy the Earth.

The Popol Vuh implies that gods could mix and match their powers at will, but other religious texts are more explicit. One thousand years before the Popol Vuh was written, there was a different version of Huracán called K’awiil. During the first millennium, people from southern Mexico to western Honduras venerated him as a god of agriculture, lightning and royalty.

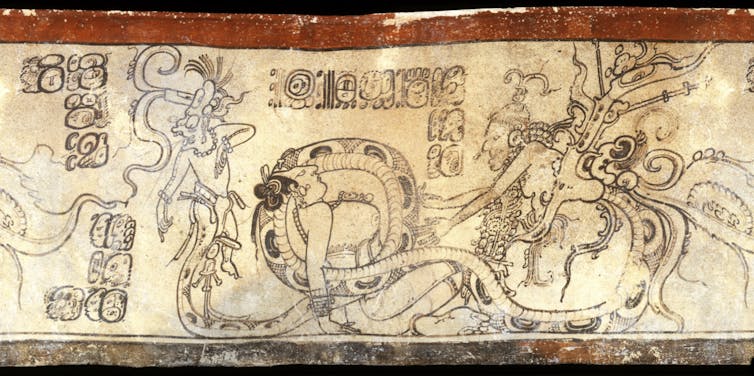

Illustrations of K’awiil can be found everywhere on Maya pottery and sculpture. He is almost human in many depictions: He has two arms, two legs and a head. But his forehead is the spark of life – and so it usually has something that produces sparks sticking out of it, such as a flint ax or a flaming torch. And one of his legs does not end in a foot. In its place is a snake with an open mouth, from which another being often emerges.

Indeed, rulers, and even gods, once performed ceremonies to K’awiil in order to try and summon other supernatural beings. As personified lightning, he was believed to create portals to other worlds, through which ancestors and gods might travel.

For the ancient Maya, lightning was raw power. It was basic to all creation and destruction. Because of this, the ancient Maya carved and painted many images of K’awiil. Scribes wrote about him as a kind of energy – as a god with “many faces,” or even as part of a triad similar to Huracán.

He was everywhere in ancient Maya art. But he was also never the focus. As raw power, he was used by others to achieve their ends.

Rain gods, for example, wielded him like an ax, creating sparks in seeds for agriculture. Conjurers summoned him, but mostly because they believed he could help them communicate with other creatures from other worlds. Rulers even carried scepters fashioned in his image during dances and processions.

Moreover, Maya artists always had K’awiil doing something or being used to make something happen. They believed that power was something you did, not something you had. Like a bolt of lightning, power was always shifting, always in motion.

Because of this, the ancient Maya thought that reality was not static but ever-changing. There were no strict boundaries between space and time, the forces of nature or the animate and inanimate worlds.

Everything was malleable and interdependent. Theoretically, anything could become anything else – and everything was potentially a living being. Rulers could ritually turn themselves into gods. Sculptures could be hacked to death. Even natural features such as mountains were believed to be alive.

These ideas – common in pantheist societies – persist today in some communities in the Americas.

They were once mainstream, however, and were a part of K’iche’ religion 1,000 years later, in the time of Huracán. One of the lessons of the Popol Vuh, told during the episode where Huracán clouds human vision, is that the human perception of reality is an illusion.

The illusion is not that different things exist. Rather it is that they exist independent from one another. Huracán, in this sense, damaged himself by damaging his creations.

Hurricane season every year should remind us that human beings are not independent from nature but part of it. And like Hurácan, when we damage nature, we damage ourselves.

James L. Fitzsimmons, Professor of Anthropology, Middlebury

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

It is such a powerful message, that when we damage nature, we damage ourselves.

But I am unaware, no we are both unaware of a solution, and there doesn’t appear to be a government desire to make this the number one topic.

Please, if there is anyone who reads this post and has a more positive message then we would be very keen to hear from you.

A fascinating article makes a fundamental point.

My mother and father were atheists so when I was born in 1944 it was obvious that I would be brought up as an atheist. Same for my sister, Elizabeth, born in 1948. It was amazing that when I met Jean in Mexico in 2007 that she, too, was an atheist. That was on top of the fact that we were both born in North London some 26 miles apart. Talk about fate!

So naturally my attention was drawn to a recent article in Free Enquiry magazine, Thinking Made Me an Atheist.

That article opens as follows:

I was abused as a child. The abuse to which I was subjected is called “child indoctrination,” a type of brainwashing considered noble and necessary and, therefore, the most natural thing in the world.

My mother took me to the Seventh-day Adventist Church, an American denomination known for keeping the Sabbath and emphasizing the advent, or return, of Jesus. Adventists boast that they are the only ones to interpret the Bible the way its author wanted. Consequently, they deem themselves the most special creatures to God—so special that they’ll soon arouse the envy and wrath of all other denominations and religions, which, under the command of the beasts of Revelation (the American government and the Catholic Church), will persecute them. Adventists believe that the Earth was created in six days, that it is 6,000 years old, and that dinosaurs are extinct because they were too big to be saved on Noah’s ark.

It closes thus:

I don’t want to believe; I want to know. Atheism is a natural result of intellectual honesty.

The author of the article, Paulo Bittencourt is described as:

Paulo Bittencourt was born in Castro, Brazil, spent his childhood in Rio de Janeiro, and studied theology in São Paulo. Close to becoming a pastor, he went on an adventure to Europe and ended up settling in Austria, where he trained as an opera singer. Bittencourt is the author of the books Liberated from Religion: The Inestimable Pleasure of Being a Freethinker and Wasting Time on God: Why I Am an Atheist.

So once again, do read this article.

We sincerely believe there is no god!

A great post on WebMD.

Now I appreciate that many who come to this place are not seniors but as I approach 80 that makes me most definitely a senior.

So this article was highly relevant.

ooOOoo

Medically Reviewed by Poonam Sachdev on October 12, 2023

Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors

Any dog owner can tell you there’s nothing like having a loyal companion. Dogs are good pets for people of any age, as long as you choose the right dog for your lifestyle.

If you’re an older adult looking to find a furry, four-legged friend, here are a few things you should consider.

It’s a big responsibility, but the benefits are worth the work. Dogs can give you joy, companionship, and unconditional love. They can bring warmth and comfort into your life.

Better health. Decades of studies have shown the health benefits of spending time with dogs. Dog owners tend to have better heart and blood vessel health, including lower blood pressure, than those who don’t have a pet pup. That’s because dogs get people moving. Walking a dog regularly can help you boost how much exercise you get each day.

Less lonely. Dogs offer companionship just by being around. They might also help you be more social. Taking your dog on walks gives you a chance to meet neighbors or other canine owners at the local dog park.

Much happier. Looking at your dog can release a hormone that makes you feel happier. Science shows that gazing into your dog’s eye releases oxytocin. Known as the love hormone, oxytocin quickly boosts your mood.

Before you get a furry pal, you should think about what you can offer the dog, as well as what they can offer you. You want to make sure to choose a dog that will be happy with the kind of life you lead. Consider these things when you start looking for a new pet.

Space. How much room do you have indoors and outdoors? You need to pick a dog that will be happy with the space you have to offer.

Exercise. Some dogs need a lot of exercise, while others are happy hanging out on the couch all day. Think about how much exercise time you can give your pup. Also, think about how fit you are. You may not want a large, strong dog that could tug hard on the leash and cause you to get hurt on a walk.

Cost. All dogs need vet care, food, and toys. If they need a lot of grooming, you need to consider paying a professional groomer.

Age. Puppies are cute, but they’re also a lot of work. Older dogs may already have some training, but they might be set in their ways. Spend some time thinking about what you’re willing to accept in dog behavior.

Here are a few breeds that are natural choices for older adults.

Bichon Frise. These dogs are very small and cute. Their fluffy coats need regular grooming. They’re happy in small homes and apartments, and they only need moderate exercise.

Cocker spaniels. These dogs are known for their beautiful, soft coats, which need regular grooming. They’re gentle and friendly, and usually weigh under 30 pounds. They need regular walks to stay fit, but they aren’t highly energetic.

Beagles. They’re small, smart, and make wonderful companions. Their short coats are easy to groom. Beagles are energetic and need a lot of exercise every day.

Greyhounds. They can run fast, but they don’t always want to. They’re happiest lounging around indoors, but they need walks to stay fit. They’re large, usually weighing around 60 pounds, but they have short coats that don’t require a lot of grooming.

Pugs. These happy little dogs make great companions. They’re usually around 15 pounds and have short, easy-to-groom coats. They need more exercise than they want because they’re prone to be overweight. Regular walks can take care of that.

If you’re an older adult looking for a four-legged companion, you can speak to a veterinarian or a dog trainer in your area for more information. They can help you choose the perfect pet.

ooOOoo

I am certain there are many people who will find this a practical help in deciding what dog to get.

In my own case we currently have two dogs, Cleo and Oliver, and I frequently ponder on what Jean and I do when the last of them dies.

This article reminds me and Jean that at whatever age we are it is better to have a dog than not!

I love this!

I am writing this having listened to a programme on BBC Radio 4. (Was broadcast on Radio 4 on Tuesday, August 13th.) It shows how many, many people can have a really positive response to a dastardly negative occurrence such as the Covid outbreak or a pandemic.

ooOOoo

Mark Honigsbaum, City, University of London

Every Friday, volunteers gather on the Albert Embankment at the River Thames in London to lovingly retouch thousands of red hearts inscribed on a Portland stone wall directly opposite the Houses of Parliament. Each heart is dedicated to a British victim of COVID. It is a deeply social space – a place where the COVID bereaved come together to honour their dead and share memories.

The so-called National Covid Memorial Wall is not, however, officially sanctioned. In fact, ever since activists from COVID-19 Bereaved Families for Justice (CBFFJ) daubed the first hearts on the wall in March 2021 it has been a thorn in the side of the authorities.

Featured in the media whenever there is a new revelation about partygate, the wall is a symbol of the government’s blundering response to the pandemic and an implicit rebuke to former prime minister Boris Johnson and other government staff who breached coronavirus restrictions.

As one writer put it, viewed from parliament the hearts resemble “a reproachful smear of blood”. Little wonder that the only time Johnson visited the wall was under the cover of darkness to avoid the TV cameras. His successor Rishi Sunak has been similarly reluctant to acknowledge the wall or say what might take its place as a more formal memorial to those lost in the pandemic.

Though in April the UK Commission on COVID Commemoration presented Sunak with a report on how the pandemic should be remembered, Sunak has yet to reveal the commission’s recommendations.

Lady Heather Hallett, the former high court judge who chairs the public inquiry into COVID, has attempted to acknowledge the trauma of the bereaved by commissioning a tapestry to capture the experiences of people who “suffered hardship and loss” during the pandemic. Yet such initiatives are no substitute for state-sponsored memorials.

This political vacuum is odd when you consider that the United Kingdom, like other countries, engages in many other commemorative activities central to national identity. The fallen of the first world war and other military conflicts are commemorated in a Remembrance Sunday ceremony held every November at the Cenotaph in London, for example.

But while wars lend themselves to compelling moral narratives, it is difficult to locate meaning in the random mutations of a virus. And while wars draw on a familiar repertoire of symbols and rituals, pandemics have few templates.

For instance, despite killing more than 50 million globally, there are virtually no memorials to the 1918-1919 “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Nor does the UK have a memorial to victims of HIV/AIDS. As the memory studies scholar Astrid Erll puts it, pandemics have not been sufficiently “mediated” in collective memory.

As a rule, they do not feature in famous paintings, novels or films or in the oral histories passed down as part of family lore. Nor are they able to draw on familiar cultural materials such as poppies, gun carriages, catafalques and royal salutes. Without such symbols and schemata, Erll argues, we struggle to incorporate pandemics into our collective remembering systems.

This lacuna was brought home to me last September when tens of thousands of Britons flocked to the south bank of the Thames to pay their respects to Britain’s longest serving monarch. By coincidence, the police directed the queue for the late Queen’s lying-in-state in Westminster Hall over Lambeth Bridge and along Albert Embankment.

But few of the people I spoke to in the queue seemed to realise what the hearts signified. It was as if the spectacle of a royal death had eclipsed the suffering of the COVID bereaved, rendering the wall all but invisible.

Another place where the pandemic could be embedded in collective memory is at the public inquiry. Opening the preliminary hearing last October into the UK’s resilience and preparedness for a pandemic, Lady Hallett promised to put the estimated 6.8 million Britons mourning the death of a family member or friend to COVID at the heart of the legal process. “I am listening to them; their loss will be recognised,” she said.

But though Lady Hallett has strategically placed photographs of the hearts throughout the inquiry’s offices in Bayswater and has invited the bereaved to relate their experiences to “Every Story Matters”, the hearing room is dominated by ranks of lawyers. And except when a prominent minister or official is called to testify, the proceedings rarely make the news.

This is partly the fault of the inquiry process itself. The hearings are due to last until 2025, with the report on the first stage of the process not expected until the summer of 2024. As Lucy Easthope, an emergency planner and veteran of several disasters, puts it: “one of the most painful frustrations of the inquiry will be temporal. It will simply take too long.”

The inquiry has also been beset by bureaucratic obfuscation, not least by the Cabinet Office which attempted (unsuccessfully in the end) to block the release of WhatsApp messages relating to discussions between ministers and Downing Street officials in the run-up to lockdown.

To the inquiry’s critics, the obvious parallel is with the Grenfell inquiry, which promised to “learn lessons” from the devastating fire that engulfed the west London tower in 2017 but has so far ended up blurring the lines of corporate responsibility and forestalling a political reckoning.

The real work of holding the government to account and making memories takes place every Friday at the wall and the other places where people come together to spontaneously mourn and remember absent loved ones. These are the lives that demand to be “seen”. They are the ghosts that haunt our amnesic political culture.

Mark Honigsbaum, Senior Lecturer in Journalism, City, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

plus Wikipedia have a long article on the National Covid Memorial Wall. That then takes us to the website for the wall.

ooOOoo

As was written in the last sentence of the article; ‘They are the ghosts that haunt our amnesic political culture.‘

Humans are a strange lot and I most certainly count myself in!

This is a lovely story from The Dodo.

I saw this article in the August 23rd issue of The Dodo magazine and it appealed to me.

So I wanted to share it with you all.

ooOOoo

Published on Aug 23, 2024

Ellie Woods’ family dog Bobby has always been an important part of her love story with her wife Georgie Woods. When Ellie brought Georgie home for the first time, the family member she was most anxious for Georgie to meet was Bobby.

When the couple got engaged and started planning their wedding, they decided it would be fun to try to document the wedding from Bobby’s unique perspective. So right before the ceremony started, they attached a GoPro to Bobby’s back and then set him loose.

For some dogs, walking around with a camera on their back might take some getting used to — but not for Bobby. He immediately felt comfortable.

“He loves being the center of attention,” Georgie told The Dodo. “He just loved it.”

Georgie and Ellie said having Bobby at their wedding was incredibly meaningful for them.

“Animals are really important to queer couples,” Ellie said. “[I]t was so important to have him … as part of our big day.

When the newlyweds sat down to watch the footage Bobby had captured, what they saw surprised and delighted them. The GoPro had caught Bobby stealing hors d’oeuvres and even walking in on Georgie’s sister in the bathroom. While Bobby is an expert videographer, he is still a dog, after all.

Of course, Bobby’s camera recorded much more than shenanigans. Georgie and Ellie loved watching themselves walk down the aisle together from Bobby’s perspective.

“It captured some really special moments,” Ellie said. “[W]e couldn’t be happier for how it came out because it’s just so organic and such an interesting, different perspective.”

ooOOoo

Dogs are just incredible. As much as I have already said that, time and time again there comes a story that just reinforces that previous sentence.

All of them were white puppies, and …

This was a story that recently was shown on The Dodo site.

Too many dogs, and cats, are abandoned on a regular basis. But read on and see why this rescue was extra special.

ooOOoo

Rescue Finds A Box Of Puppies Abandoned On Their Property — And Then They Realize Why.

By Caitlin Jill Anders, Published on Aug 15, 2024

When staff members and volunteers at Saving Hope Rescue noticed a box had been dumped on their property, their hearts sank. As they got closer, they saw the box had “puppies her” written on the side of it and had a feeling they knew who was inside.

When they opened the box, the rescuers came face-to-face with a whole pile of all-white puppies. Even though their rescue was already at capacity, they knew they couldn’t turn their backs on the sweet little family. They put out a call for help to the community in order to get some support and began to get the pups settled in.

As everyone at the rescue started getting to know the abandoned puppies, they realized that the pups had been hiding something: Apparently, they were all visually and hearing impaired to some degree.

“At first, they were all deemed blind and deaf,” Lauren Anton of Saving Hope Rescue told The Dodo. “Eventually, as time went by and they developed some more, we discovered that some puppies are more impaired than others.”

It’s possible that this was the reason the puppies were abandoned in the first place, but it’s hard to know for sure. Either way, it didn’t change anything for the puppies’ rescuers. Even if they might need a little extra help, they were still members of the Saving Hope family.

As the puppies grew, their unique personalities began to shine through, and their rescuers were also able to start getting an accurate picture of their different abilities.

“Mate is a good example of the slightly impaired puppies,” Anton said. “We don’t know how much she can see and hear, for sure, but we do know that she can hear being called, knows when we shake the food bag, and will approach people when called to come over … Koala, on the other hand, is much more impaired … We aren’t sure how much he can see. Maybe just shadows.”

Everyone is doing their best to get to know the puppies and their individual needs so they’ll know how to best help them as they grow. One thing is for sure though, the puppies are happy and thriving.

“Over the last few weeks, they’ve gone from sleepy babies to rambunctious puppies,” Anton said. “They’re constantly playing and wrestling with each other. They’ve learned that human pets and snuggles feel nice, and they love to sleep in our arms.”

These puppies may have been abandoned, but now they’re getting the second chance they deserve.

ooOOoo

That is a beautiful story. Lauren and the staff are to be congratulated on doing what they did, and that was giving these puppies a new lease of life.