More of these fabulous photographs.

Again, taken from the AKC website.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

Wonderful!

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Year: 2020

More of these fabulous photographs.

Again, taken from the AKC website.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

Wonderful!

Yet another guest post!

One of the lovely things about writing a blog about dogs is that frequently people ‘pop up’ and offer a guest post. So it was with Eliza, or Eliza Gilbert to give to her her full name. This is a brief background that she sent me.

ooOOoo

NB: It’s the morning of Tuesday, the 11th February, 2020 and I have had to do something for the very first time. That is delete a guest post.

It turned out that Eliza was pushing me to include a link for her client and it was far from being a guest post, more like a commercial arrangement between Eliza and her client. I hope everyone understands.

ooOOoo

There really is no end to the sense of smell that a dog has.

I was browsing online The Smithsonian magazine and came across a long article that was all about the dog’s sense of smell in terms of sniffing out citrus greening disease.

There’s no end of articles about the dog’s sense of smell and I have written about it before. But first I’m going to reproduce the article on Animal Planet because it gets to the point.

Dogs rule. Or, at least, they do when it comes to their sense of smell, which crushes that of humans. According to the Alabama Cooperative Extension System (ACES), a dog’s sense of smell is about 1,000 times keener than that of their two-legged companions — and many dog experts claim it’s millions of times better — thanks to the construction of their often-slobbery, wet schnozzes. So what, exactly, is going on in there?

A dog sniffs at scents using his nose, of course, and also his mouth, which may open in a sort of grin. His nostrils, or nares, can move independently of one another, which helps him pinpoint where a particular smell is coming from. As a dog inhales a scent, it settles into his spacious nasal cavity, which is divided into two chambers and, ACES reports, is home to more than 220 million olfactory receptors (humans have a measly 5 million). Mucus traps the scent particles inside the nasal chambers while the olfactory receptors process them. Additional particles are trapped in the mucus on the exterior surface of his nose.

Sometimes, it takes more than one sniff for a dog to accumulate enough odor molecules to identify a smell. When the dog needs to exhale, air is forced out the side of his nostrils, allowing him to continue smelling the odors he’s currently sniffing.

Dogs possess another olfactory chamber called Jacobson’s organ, or, scientifically, the vomeronasal organ. Tucked at the bottom of the nasal cavity, it has two fluid-filled sacs that enable dogs to smell and taste simultaneously. Puppies use it to locate their mother’s milk, and even a favored teat. Adult dogs mainly use it when smelling animal pheromones in substances like urine, or those emitted when a female dog is in heat.

Top Sniffers

What all of this sniffing and processing really means is that a dog’s sense of smell is his primary form of communication. And it’s a phenomenal one, because dogs don’t just smell odors that we can’t. When a dog greets another dog through sniffing, for example, he’s learning an intricate tale: what the other dog’s sex is, what he ate that day, whom he interacted with, what he touched, what mood he’s in and — if it’s a female — if she’s pregnant or even if she’s had a false pregnancy. It’s no wonder, then, that while a dog’s brain is only one-tenth the size of a human brain, the portion controlling smell is 40 times larger than in humans.

So, who’s top dog when it comes to sniffing? While all canines have an incredible sense of smell, some breeds — such as bloodhounds, basset hounds and beagles — have more highly refined sniffers. This is a result of several factors. Dogs with longer snouts, for example, can smell better simply because their noses have more olfactory glands. Bloodhounds, members of the “scent hound” canine group, also have lots of skin folds around their faces, which help to trap scent particles. And their long ears, like those of Bassets, drag on the ground, collecting more smells that can be easily swept into their noses.

Of course, dogs are individuals as well, so it’s certainly possible to find a non-scent-hound who can outperform one. And as Dr. Sandi Sawchuk, a clinical instructor at the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine, notes: “There are lots of breeds that can be trained to sniff out certain items — for example, cadaver-sniffing dogs, drug-sniffing dogs, etc.”

Now to that longer Smithsonian article.

ooOOoo

Once trained, canines can detect citrus greening disease earlier and more accurately than current diagnostics

By Katherine J. Wu , smithsonianmag.com

Feb. 3, 2020

Tim Gottwald will never forget the sight: the mottled yellow leaves, the withered branches, the small, misshapen fruits, tinged with sickly green. These were the signs he’d learned to associate with huanglongbing, or citrus greening—a devastating and wildly infectious bacterial infection that slashed the United States’ orange juice yields by more than 70 percent in the span of a decade.

“It’s like a cancer,” says Gottwald, a plant pathologist with the United States Department of Agriculture. “One that’s metastasized, and can’t be eradicated or cured.”

Once they’ve begun to sport splotchy foliage and stunted fruit, trees can be diagnosed with a single glance. A symptomatic plant, Gottwald says, is a diseased one. Unfortunately, the converse isn’t true: Infected trees can appear normal for months, sometimes years, before visibly deteriorating, leaving researchers with few reliable ways to suss out sick citrus early on—and giving the deadly bacteria ample opportunity to spread unnoticed.

Now, Gottwald and his colleagues may have a creative new strategy to fill this diagnostic gap—one that relies not on vision, but smell. They’ve taught dogs to recognize the telltale scent of a huanglongbing infection—an odor that eludes the attention of humans, but consistently tickles the super-sensitive schnozz of a mutt. Once trained up, canines can nose out the disease within weeks of infection, trouncing all other available detection methods in both timing and accuracy, the researchers report today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This is a major step in the development of what could be a really important early detection tool,” says Monique Rivera, an entomologist and citrus pest expert at the University of California, Riverside who wasn’t involved in the study. “It could give growers information about potential exposure … to the causative bacteria.”

First described in China in the early 1900s, huanglongbing has now crippled orchards in more than 50 countries around the globe. Fifteen years ago, the scourge took hold in Florida, where infected trees are now the norm; the state’s $9 billion citrus industry, once the second largest in the world, is now on the verge of collapse. From oranges to grapefruits to lemons, no variety of citrus is immune.

As the disease continues to creep into new regions, researchers worldwide are scrambling to contain it. But the task has proved difficult: No effective treatments, cures or vaccines exist for huanglongbing, the product of a bacterium called Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (or CLas, pronounced “sea lass”) that’s ferried from tree to tree by winged insects. Scientists have also found the microbes to be extraordinarily difficult to grow and study in the lab.

Currently, the only surefire way to curb citrus greening’s spread is to extract and eliminate infected trees. This strategy depends entirely on early detection—“one of the biggest problems in the field right now,” says Carolyn Slupsky, a plant pathologist at the University of California, Davis who wasn’t involved in the study. Spotting an asymptomatic infection by eye is essentially impossible. And though genetic tests can sometimes pinpoint microbes in apparently healthy trees, their success rates are low and inconsistent, due in part to the patchiness with which CLas distributes itself in plant tissue.

In many ways, huanglongbing is “the perfect storm of a disease,” Slupsky says.

But canines may just be the perfect candidates to lend a helping paw. With a sense of smell that’s 10,000 to 100,000 times more powerful than a human’s, dogs are superstar sniffers, capable of nosing out everything from bombs to drugs. In recent years, they’ve even been deployed to detect pathogenic diseases like malaria. Infections, it turns out, stink—and dogs definitely take notice.

To see if pooches’ powers of perception might extend to huanglongbing, Gottwald and his team taught 20 dogs to pick up on the smell of citrus plants with known infections, rewarding the pups with toys when they identified the correct trees. After just a few weeks of training, the newly-minted citrus sniffers were picking out infected trees with about 99 percent accuracy. Put in pairs to corroborate each other’s results, the dogs got close-to-perfect scores.

Gottwald was floored. “I wasn’t surprised [the dogs] could do it,” he says. “But I was surprised by how well they could do it. It was pretty amazing.”

The team then pitted the pups against a common but expensive laboratory test that’s often used to verify the presence of CLas DNA in suspicious-looking citrus. After spiking the microbes into 30 trees, the researchers mixed the newly-infected plants into rows of healthy ones and allowed the dogs to inspect them on a weekly basis. Within a month, the canines had collectively homed in on every single CLas-positive plant.

The DNA test, on the other hand, had no such luck: Seventeen months into the infection, it was still failing to identify a third of the diseased trees.

If Gottwald’s team sees continued success, “this could be very exciting for [citrus] growers,” who could someday keep dogs around as a fast and relatively inexpensive way to survey their orchards, says Phuc Ha, a microbiologist at Washington State University who wasn’t involved in the study. For now, the most immediate applications lie in disease prevention. But, she adds, should researchers develop treatments for huanglongbing, canines could eventually play a role in curing the condition as well.

Gottwald and his team have already begun to send small teams of citrus-sniffer dogs to inspect vulnerable trees in California and Texas. In both locations, the canines have alerted the researchers to trees that have yet to test positive in the lab.

This, however, evokes the double-edged sword of early detection research: The dogs are so much faster at finding potentially diseased trees that their picks can’t actually be confirmed, Slupsky points out. Maybe they’re more sensitive than the molecular test, and the disease is more widespread than researchers feared. Or maybe the canine’s noses are leading them astray. “Specificity is always an issue,” Slupsky says, “because you’re comparing them to an imperfect test.”

Dogs also come with their own drawbacks. They can tire; they can be distracted. They’re not machines. And while they can make fast work of orchards where infections are rare, their performance will probably plummet in heavily afflicted groves. In an ideal world, Slupsky says, the dogs would serve strictly as a first line of defense, screening trees for further monitoring or testing in the lab. She and her colleagues are hard at work on one such diagnostic, built to detect the unique suite of chemicals infected leaves produce early on.

Many questions remain unanswered. Gottwald still isn’t sure what exactly the dogs are smelling on the plants, though a series of experiments indicate the scent is probably coming from the CLas bacteria themselves. That theory may be tough to test: Though researchers like Washington State’s Ha have now grown CLas in the presence of other microbes, no one has yet managed to isolate the strain in a pure culture, hampering efforts to understand its basic biology and develop precise treatments.

While exciting, the team’s dog-nostic developments ultimately underscore “just how distant we still are from understanding a lot of the mechanistic processes that are going on [with this disease],” Rivera says. But with more collaboration and multidisciplinary work, she adds, “I think we’ll keep heading toward solutions.”

ooOOoo

When one watches a dog closely it’s very clear that their nose is their primary sense. At least a thousand times better than our human sense of smell and some people put it much higher. That is impossible to understand. The best we can do is to wonder at the sort of world that dogs ‘see’ with their noses.

I will close with an old photograph of Pharaoh helping a prospector look for gold in our creek.

And back to The Conversation.

I was discussing with Mr. P. (he of Wibble) yesterday the pros and cons of republishing material from The Conversation and I noticed this recent essay there.

It’s a very positive message but I will let you read it in full.

ooOOoo

R. Claudio Aguilar, Purdue University

Can the feared anthrax toxin become an ally in the war against cancer? Successful treatment of pet dogs suffering bladder cancer with an anthrax-related treatment suggest so.

Anthrax is a disease caused by a bacterium, known as Bacillus anthracis, which releases a toxin that causes the skin to break down and forms ulcers, and triggers pneumonia and muscle and chest pain. To add to its sinister resumé, and underscore its lethal effects, this toxin has been infamously used as a bioweapon.

However, my colleagues and I found a way to tame this killer and put it to good use against another menace: bladder cancer.

I am a biochemist and cell biologist who has been working on research and development of novel therapeutic approaches against cancer and genetic diseases for more than 20 years. Our lab has investigated, designed and adapted agents to fight disease; this is our latest exciting story.

Among all cancers, the one affecting the bladder is the sixth most common and in 2019 caused more than 17,000 deaths in the U.S.

Of all patients that receive surgery to remove this cancer, about 70% will return to the physician’s office with more tumors. This is psychologically devastating for the patient and makes the cancer of the bladder one of the most expensive to treat.

To make things worse, currently there is a worldwide shortage of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, a bacterium used to make the preferred immunotherapy for decreasing bladder cancer recurrence after surgery. This situation has left doctors struggling to meet the needs of their patients. Therefore, there is a clear need for more effective strategies to treat bladder cancer.

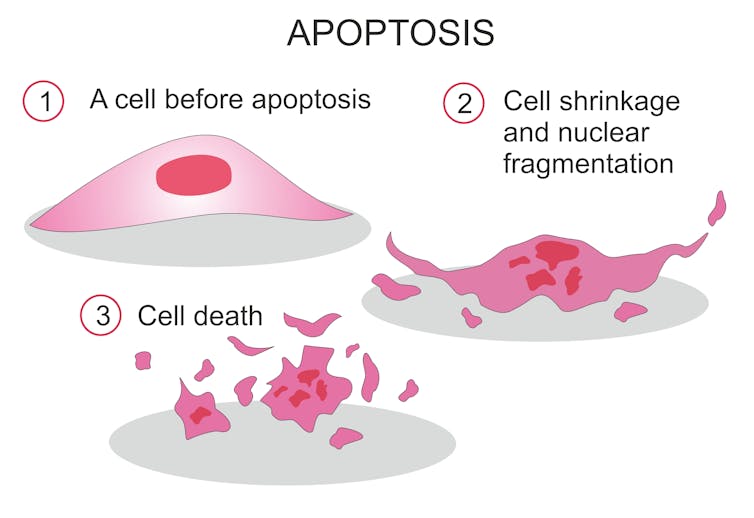

Years ago scientists in the Collier lab modified the anthrax toxin by physically linking it to a naturally occurring protein called the epidermal growth factor (EGF) that binds to the EGF receptor, which is abundant on the surface of bladder cancer cells. When the EGF protein binds to the receptor – like a key fits a lock – it causes the cell to engulf the EGF-anthrax toxin, which then induces the cancer cell to commit suicide (a process called apoptosis), while leaving healthy cells alone.

In collaboration with colleagues at Indiana University medical school, Harvard University and MIT, we designed a strategy to eliminate tumors using this modified toxin. Together we demonstrated that this novel approach allowed us to eliminate tumor cells taken from human, dog and mouse bladder cancer.

This highlights the potential of this agent to provide an efficient and fast alternative to the current treatments (which can take between two and three hours to administer over a period of months). I also think it is good news is that the modified anthrax toxin spared normal cells. This suggests that this treatment could have fewer side effects.

These encouraging results led my lab to join forces with Dr. Knapp’s group at the Purdue veterinary hospital to treat pet dogs suffering from bladder cancer.

Canine patients for whom all available conventional anti-cancer therapeutics were unsuccessful were considered eligible for these tests. Only after standard tests proved the agent to be safe in laboratory animals, and with the consent of their owners, six eligible dogs with terminal bladder cancer were treated with the anthrax toxin-derived agent.

Two to five doses of this medicine, delivered directly inside the bladder via a catheter, was enough to shrink the tumor by an average of 30%. We consider these results impressive given the initial large size of the tumor and its resistance to other treatments.

Our collaborators at Indiana University Hospital surgically removed bladder cells from human patients and sent them to my lab for testing the agent. At Purdue my team found these cells to be very sensitive to the anthrax toxin-derived agent as well. These results suggest that this novel anti-bladder cancer strategy could be effective in human patients.

The treatment strategy that we have devised is still experimental. Therefore, it is not available for treatment of human patients yet. Nevertheless, my team is actively seeking the needed economic support and required approvals to move this therapeutic approach into human clinical trials. Plans to develop a new, even better generation of agents and to expand their application to the fight against other cancers are ongoing.

R. Claudio Aguilar, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

So I republished this from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing rules. As they put it:

You are free to republish this article both online and in print. We ask that you follow some simple guidelines.

Please do not edit the piece, ensure that you attribute the author, their institute, and mention that the article was originally published on The Conversation.

Regular readers of this place may notice some subtle differences because up until now I had just copied and pasted the article as posted.

Another essay that is nothing to do with dogs!

I have long been a subscriber to The Conversation. They seem to be politically neutral as well as giving permission for their essays to be republished elsewhere.

This particular essay chimed with me because for some time, one or two years sort of time-span, the number of people agreeing with the statement, “It’s a strange world“, has measurably grown. At first I thought it was a question of politics, both sides of The Atlantic, but I have recently come to the opinion that it is deeper than that.

This encapsulates the idea perfectly.

ooOOoo

By , Professor of Ethics and Business Law, University of St. Thomas

January 27, 2020

We live in a world threatened by numerous existential risks that no country or organization can resolve alone, such as climate change, extreme weather and the coronavirus.

But in order to adequately address them, we need agreement on which are priorities – and which aren’t.

As it happens, the policymakers and business leaders who largely determine which risks become global priorities spent a week in January mingling in the mountainous resort of Davos for an annual meeting of the world’s elite.

I participated in a global risk assessment survey that informed those at the Davos summit on what they should be paying the most attention to. The results, drawn from experts in a broad range of disciplines including business, happen to be very different from what company CEOs specifically see as the biggest threats they face.

As a philosopher, I found the differences curious. They highlight two contrasting ways of seeing the world – with significant consequences for our ability to address societal risks.

Two perspectives on the biggest risks

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Report consolidates the perceptions of about 800 experts in business, government and civil society to rank “the world’s most pressing challenges” for the coming year by likelihood and impact.

In 2020, extreme weather, a failure to act on climate change and natural disasters topped the list of risks in terms of likelihood of occurrence. In terms of impact, the top three were climate action failure, weapons of mass destruction and a loss of biodiversity.

The specific perspective of corporate leaders, however, is captured in another survey that highlights what they perceive as the biggest risks to their own businesses’ growth prospects. Conducted by consultancy PwC since 1998, it also holds sway in Davos. I’ve been involved in that report as well when I used to work for the organization.

In sharp contrast to the World Economic Forum’s risk report, the CEO survey found that the top three risks to business this year are overregulation, trade conflicts and uncertain economic growth.

Economic or ethical

What explains such a big difference in how these groups see the greatest threats?

I wanted to look at this question more deeply, beyond one year’s assessment, so I did a simple analysis of 14 years of data generated by the two reports. My findings are only inferences from publicly available data, and it should be noted that the two surveys have different methodologies and ask different questions that may shape respondents’ answers.

A key difference I observed is that business leaders tend to think in economic terms first and ethical terms second. That is, businesses, as you’d expect, tend to focus on their short-term economic situation, while civil society and other experts in the Global Risk Report focus on longer-term social and environmental consequences.

For example, year after year, CEOs have named a comparatively stable set of narrow concerns. Overregulation is among the main three threats in all but one of the years – and is frequently at the top of the list. Availability of talent, government fiscal concerns and the economy were also frequently mentioned over the past 14 years.

In contrast, the Global Risk Report tends to reflect a greater evolution in the types of risks the world faces, with concerns about the environment and existential threats growing increasingly prominent over the past five years, while economic and geopolitical risks have faded after dominating in the late 2000s.

A philosophical perspective

Risk surveys are useful tools for understanding what matters to CEOs and civil society. Philosophy is useful for considering why their priorities differ, and whose are likelier to be right.

Fundamentally, risks are about interests. Businesses want a minimum of regulations so they can make more money today. Experts representing constituencies beyond just business place a greater emphasis on the common good, now and in the future.

When interests are in tension, philosophy can help us sort between them. And while I’m sympathetic to CEOs’ desire to run their businesses without regulatory interference, I’m concerned that these short-term economic considerations often impede long-term ethical goals, such as looking after the well-being of the environment.

An uncertain world

Experts agree on at least one thing: The world faces dire risks.

This year’s Global Risk Report, titled, “An Unsettled World,” depicts on its cover a vulnerable earth in the shadow of a gigantic whirlpool.

The cover photograph of the Global CEO Survey, which reported the lowest CEO confidence in economic growth since the Great Recession, shows an incoming tide beneath looming dark clouds, with the words: “Navigating the Rising Tide of Uncertainty.”

Between the covers, however, the reports demonstrate a wide gap between two influential groups that need to be on the same page if we hope to resolve the world’s biggest threats.

Last century, in the same year that World War II drew to a close, Bertrand Russell proclaimed that

the purpose of philosophy was to teach us “how to live without certainty, and yet without being paralyzed by hesitation.”

In the 21st century, philosophy can remind us of our unfortunate tendency to let economic priorities paralyze action on more pressing concerns.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]

ooOOoo

Bertrand Russell was a great philosopher. Well he was that and much more. Wikipedia remind us that he “was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, writer, essayist, social critic, political activist, and Nobel laureate.”

He died at the age of 97 on the 2nd February, 1970; fifty years ago as of yesterday.

I’ll close with another quote from the great man: