Now this is interesting!

I first received notice of this story from a news release put by Uppsala University. That news release is what I publish as it is a short-form of the full scientific report. But I will also include an extract of the report as there may be some of you that will want to go further into this.

ooOOoo

Owning a dog is influenced by our genetic make-up

NEWS RELEASE

UPPSALA UNIVERSITY

A team of Swedish and British scientists have studied the heritability of dog ownership using information from 35,035 twin pairs from the Swedish Twin Registry. The new study suggests that genetic variation explains more than half of the variation in dog ownership, implying that the choice of getting a dog is heavily influenced by an individual’s genetic make-up.

Dogs were the first domesticated animal and have had a close relationship with humans for at least 15,000 years. Today, dogs are common pets in our society and are considered to increase the well-being and health of their owners. The team compared the genetic make-up of twins (using the Swedish Twin Registry – the largest of its kind in the world) with dog ownership. The results are published for the first time in Scientific Reports. The goal was to determine whether dog ownership has a heritable component.

“We were surprised to see that a person’s genetic make-up appears to be a significant influence in whether they own a dog. As such, these findings have major implications in several different fields related to understanding dog-human interaction throughout history and in modern times. Although dogs and other pets are common household members across the globe, little is known how they impact our daily life and health. Perhaps some people have a higher innate propensity to care for a pet than others.” says Tove Fall, lead author of the study, and Professor in Molecular Epidemiology at the Department of Medical Sciences and the Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala University.

Carri Westgarth, Lecturer in Human-Animal interaction at the University of Liverpool and co-author of the study, adds: “These findings are important as they suggest that supposed health benefits of owning a dog reported in some studies may be partly explained by different genetics of the people studied”.

Studying twins is a well-known method for disentangling the influences of environment and genes on our biology and behaviour. Because identical twins share their entire genome, and non-identical twins on average share only half of the genetic variation, comparisons of the within-pair concordance of dog ownership between groups can reveal whether genetics play a role in owning a dog. The researchers found concordance rates of dog ownership to be much larger in identical twins than in non-identical ones – supporting the view that genetics indeed plays a major role in the choice of owning a dog.

“These kind of twin studies cannot tell us exactly which genes are involved, but at least demonstrate for the first time that genetics and environment play about equal roles in determining dog ownership. The next obvious step is to try to identify which genetic variants affect this choice and how they relate to personality traits and other factors such as allergy” says Patrik Magnusson, senior author of the study and Associate Professor in Epidemiology at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Karolinska Insitutet, Sweden and Head of the Swedish Twin Registry.

“The study has major implications for understanding the deep and enigmatic history of dog domestication” says zooarchaeologist and co-author of the study Keith Dobney, Chair of Human Palaeoecology in the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool. “Decades of archaeological research have helped us construct a better picture of where and when dogs entered into the human world, but modern and ancient genetic data are now allowing us to directly explore why and how?”

ooOOoo

Now here’s the full report as published by Nature.com. And below I present the Introduction.

ooOOoo

Evidence of large genetic influences on dog ownership in the Swedish Twin Registry has implications for understanding domestication and health associations

Scientific Reports 9, Article number: 7554 (2019)

Introduction

The relationship between humans and dogs is the longest of all the domestic animals, yet the origin and history of perhaps our most iconic companion animal remains an enigma, and a topic of much ongoing scientific debate1. Decades of archaeological and more recent genetic investigations across the world have so far failed to resolve the fundamental questions of where, when and why wolves formed the transformational partnership with humans that finally resulted in the first domestic dog.

Although recent claims for the existence of so-called “Palaeolithic dogs”2,3,4,5 as early as 30,000 years ago remain controversial6,7, there is incontrovertible evidence for the existence of domestic dogs in pre-farming hunter-gatherer societies in Europe at least 15,000 years ago, the Far East 12,500, and the Americas 10,000 years ago8,9,10.

Over the subsequent millennia this ‘special relationship’ developed apace throughout most cultures of the world and is as strong and complex today as it has ever been. Dogs have long been important as an extension to the human ‘toolkit’, assisting with various tasks such as hunting, herding, and protection, as well as for more social activities such as ritual and companionship. The diverse roles that dogs fulfilled most likely introduced a range of selective advantages to those human groups with domesticated dogs. The anthropologist Dr. Pat Shipman went so far as to suggest that the close connection between dogs, other animals and their domesticators had a significant and tangible influence on our bio-cultural history – the animal connection hypothesis11. A number of experimental studies demonstrate that the view of dogs and other animal stimuli influence human behavior and interest from early childhood onward implicating innate mechanisms12,13, whilst others conversely highlight innate adverse responses to spiders and snakes in humans, indicating the evolutionary benefits of avoiding snakes and spiders14.

Inspired by assumed physical and psychosocial benefits of dog ownership, pet dogs are now increasingly being used in interventions for the rehabilitation of prisoners15, in-patient care16 and during pediatric post-surgical care17. A large number of studies have shown dog owners to be more physically active18,19,20, leading to acquisition of a dog being recommended as an intervention to improve health. There is also evidence that dog-owners feel less lonely21 and have an improved perception of wellbeing, particularly with regard to single people and the elderly22,23,24. We have previously shown that dog ownership is associated with longevity25 and lower risk of childhood asthma26. However, there are studies showing no relation (or even an inverse one) between dog ownership and these health outcomes27,28,29. One of the important limitations of the available evidence regarding health effects of dog ownership is that it is uncertain whether health differences between dog owners and non-dog owners reflect effects of dog ownership itself, or underlying pre-existing differences in personality, health and genetics. Such factors may impact the choice to acquire a dog in adult life as well as health outcomes – although these factors are difficult to disentangle.

Previous research has indicated that exposure to pets during childhood is positively associated with more positive attitudes towards pets30 and ownership in adulthood31,32, but it is unclear if genetic differences between families contribute to this association. The heritability of a trait can be estimated from studies comparing concordance of the trait in monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic twins (DZ) using structural equation modeling. These estimations rely on the underlying assumptions that MZ and DZ twin pairs share environment to a similar degree, that MZ twins share their entire genome, and that DZ twins on average share 50% of their segregating alleles33. A previous study of twin pairs aged 51–60 indicated that genetic factors account for up to 37% of the variation in the frequency of pet play and that less than 10% is attributable to the shared childhood environment34 indicating a strong contribution of genetic factors to the amount of playful interaction with pets.

Increased understanding of a potential genetic adaption towards dog ownership would support theories of co-evolution of humans and dogs and could also aid the understanding of differences in health outcomes today. However, there are no empirical data supporting a genetic contribution to dog ownership, likely due to lack of information on dog ownership in large twin cohorts. However, it is now possible to study this using register data in Sweden. It is mandatory by law that every dog in Sweden is registered with the Swedish Board of Agriculture. Moreover, all dogs sold with a certified pedigree are also registered with the Swedish Kennel Club. A survey conducted by Statistics Sweden in 2012 estimated that 83% (95% confidence interval (CI), 78–87) of dogs are registered in either or both of the two registers35. In this study, we aimed to estimate the heritability of dog ownership in the Swedish Twin Registry, the largest twin cohort in the world.

ooOOoo

If you wish to follow up the references that appear above then please go here.

Also if you wish to examine the Tables and Figure 1 that appear in the Results then you also need to go to the same place.

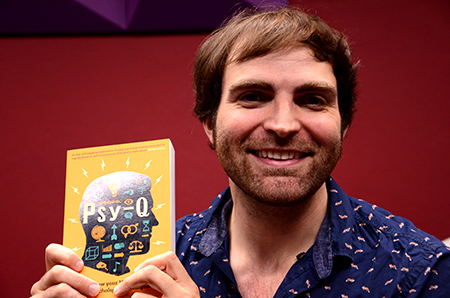

Now let me close with a picture!