Unexplored waters ahead!

My sub-title comes from personal knowledge of what it feels like to set out on an ocean voyage into waters that one has not sailed before. In my case, leaving Gibraltar bound for The Azores on my yacht Songbird of Kent in the Autumn of 1969.

Despite me being very familiar with my boat, and with sailing in general, there was nonetheless a sense of trepidation as I headed out into a vast unfamiliar ocean.

Coming to matters closer to hand, there is a sense of trepidation felt by me and countless others as to what world we are heading into if we don’t take seriously the risks that are ‘tapping on our door’.

So hold that in your mind as you read a recent essay published by Patrice Ayme’; an essay that highlights very uncertain times ahead if we, as a global society, don’t get our act together pretty damn quick. Republished here on Learning from Dogs with Patrice’s kind permission.

ooOOoo

Record Heat 2015, Obama Cool

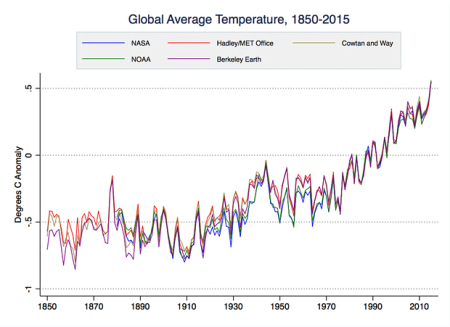

2014 was the warmest year ever recorded. 2015 was even warmer, and by far, by .16 degrees centigrade. The UK (Great Britain) meteorological office announced that the temperature rise is now a full degree C above the pre-industrial average. At this annual rate of increase, we will get to two degrees within six years (as I have predicted was a strong possibility).

What’s going on? Exponentiation. Just as wealth grows faster, the greater the wealth, mechanisms causing more heat are released, the greater the heat. Yes, it could go all the way to tsunamis caused by methane hydrates explosions. This happened in the North Atlantic during the Neolithic, leaving debris of enormous tsunamis all over Scotland.

The Neolithic settlements over what is now the bottom of the North Sea and the Franco-English Channel (then a kind of garden of Eden), probably perished the hard way, under giant waves.

Explosions of methane hydrates have started on the land, in Siberia. No tsunami, so far. But it can, and will happen, any time. The recent North Easter on the East Coast of the USA was an example of the sort of events we will see ever more of: a huge warm, moist Atlantic born air mass, lifted up by a cold front.

Notice that, at the COP 21 in Paris all parties, 195 nations, agreed to try their best to limit warming to 1.5 degree Centigrade. At the present instantaneous rate, that’s less than 4 years away. Even with maximum switching out of fossil fuels, we are, at the minimum, on a three degrees centigrade target, pretty soon.

By the way, if all nations agree, how come the “climate deniers” are still heard of so loudly? Well, plutocrats control Main Stream Media. It’s not just that they want to burn more fossil fuels (as it brings them profit, they are the most established wealth). It’s also that they want to create debates about nothing significant, thus avoiding debates about significant things, such as how much the world is controlled by Dark Pools of money.

Meanwhile, dear Paul Krugman insists in “Bernie, Hillary, Barack, and Change“, that it would be pure evil to see him as a “corrupt crook“, because he believes everything Obama says about change and all that. Says Krugman: “President Obama, in his interview with Glenn Thrush of Politico, essentially supports the Hillary Clinton theory of change over the Bernie Sanders theory:

[Says Obama]: ‘I think that what Hillary presents is a recognition that translating values into governance and delivering the goods is ultimately the job of politics, making a real-life difference to people in their day-to-day lives.’”

This is all hogwash. We are not just in a civilization crisis. We are in a biosphere crisis, unequalled in 65 million years. “Real-life differences“, under Obama, have been going down in roughly all ways. His much vaunted “Obamacare” is a big nothing. All people in the know appraise that next year, it will turn to a much worse disaster than it already is (in spite of a few improvements, “co-pays” and other enormous “deductibles” make the ironically named, Affordable Care Act, ACA, unaffordable).

The climate crisis show that there is no more day-to-day routine. At Paris, the only administration which caused problem, at the last-minute, was Obama’s. How is that, for “change”? The USA is not just “leading from behind”, but pulling in the wrong direction. Really, sit down, and think about it: under France’s admirable guidance (!), 194 countries had agreed on a legally enforceable document. Saudi Arabia agreed. The Emirates agreed. Venezuela agreed. Nigeria agreed. Russia agreed. Byelorussia agreed. China, having just made a treaty with France about climate change, actually helped France pass the treaty. Brazil agreed. Zimbabwe agreed. Mongolia agreed. And so on. But, lo and behold, on the last day, Obama did not.

I know Obama’s excuses well; they are just that, excuses. Bill Clinton used exactly the exact same excuses, 20 years ago. Obama is all for Clinton, because, thanks to Clinton, he can just repeat like a parrot what Clinton said, twenty years ago. Who need thinkers, when we have parrots, and they screech?

I sent this (and, admirably, Krugman published it!):

“No doubt Obama wants to follow the Clintons in making a great fortune, 12 months from now. What is there, not to like?

Obama’s rather insignificant activities will just be viewed, in the future, as G. W. Bush third and fourth terms. A janitor cleaning the master’s mess. Complete with colored (“bronze”) apartheid health plan.

What Sanders’ supporters are asking is to break that spiral into ever greater plutocracy (as plutocrat Bloomberg just recognized).”

Several readers approved my sobering message, yet some troll made a comment, accusing me of “racist “slander”. Racist? Yes the “bronze” plan phraseology is racist. I did not make it up. And it is also racist to make a healthcare system which is explicitly dependent upon how much one can afford. Krugman is all for it, but he is not on a “bronze” plan. Introducing apartheid in healthcare? Obama’s signature achievement. So why should we consider Obama as the greatest authority on “progressive change”? Because we are gullible? Because we cannot learn, and we cannot see? Is not that similar to accepting that Hitler was a socialist, simply because he claimed to be one, it had got to be true, and that was proven because a few million deluded characters voted for him?

We are in extreme circumstances, unheard of in 65 million years, they require extreme solutions. They do not require, nor could they stand, Bill Clinton’s Third Term (or would that be G. W. Bush’s fifth term? The mind reels through the possibilities).

“Change we can believe in”: the new boss, same as the old boss, the same exponentiation towards inequality, global warming and catastrophe, the same warm rhetoric of feel-good lies.

As it is, there is a vicious circle of disinformation between the Main Stream Media, and no change in the trajectory towards Armageddon. Yes, Obama was no change. Yes, Obama was the mountain of rhetoric, who gave birth to a mouse. Yes, we need real change, and it requires to start somewhere. And that means, not by revisiting the past.

Patrice Ayme’

ooOOoo

Yes, we do need real change, and every day that we think that this change is the responsibility of someone else then that is another day lost forever. Or in the more proasic words of Mahatma Gandi, “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.”