The last quality that I want to write about, as in the last quality that I see in our dogs that we humans should learn, is about stillness. There was a very deliberate reason to make it the last one. But, if you will forgive me, I’m not going to explain why until near the end.

Stillness! The dog is the master of being still. Being still, either from just laying quietly watching the world go by, so to speak, or being still from being fast asleep. The ease at which they can find a space on a settee, a carpeted corner of a room, the covers of a made-up bed, and stretch out and be still, simply beggars belief. Dogs offer us humans the most wonderful quality of stillness that we should all practice. Dogs reveal their wonderful relationship with stillness.

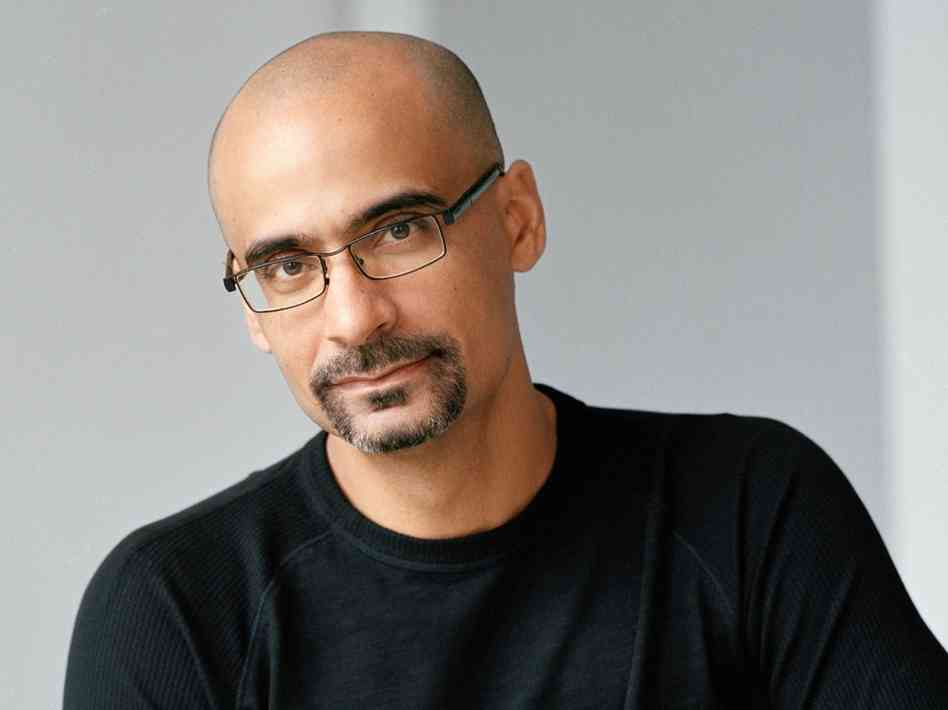

In the August of 2014, TED Talks published a talk by Pico Iyer. Despite the uncommon name, Pico Iyer was not a person I had heard of before. A quick search revealed that he was a British-born essayist and novelist of Indian origin. Apparently, Pico is the author of a number of books on crossing cultures and has been an essayist for Time Magazine since 1986. Pico Iyer’s TED Talk was called: The art of stillness.

It was utterly riveting. In a little over fifteen minutes, Pico’s talk touched on something that so many of us feel, probably even yearn for: the need for space and stillness in our minds. Stillness to offset the increasingly excessive movement and distractions of our modern world. Or to use Pico’s words:”Almost everybody I know has this sense of overdosing on information and getting dizzy living at post-human speeds.”

Now Pico has clearly been a great traveller and the list of countries and places he has visited was impressive. From Kyoto to Tibet, from Cuba to North Korea, from Bhutan to Easter Island; a man having grown up both being a part of, and yet apart from, the English, American and Indian cultures. Yet of all the places this man has been to he tops them all with what he discovers in stillness: “… that going nowhere was at least as exciting as going to Tibet or to Cuba.”

Here are Pico Iyer’s own words from that TED Talk. Firstly:

And by going nowhere, I mean nothing more intimidating than taking a few minutes out of every day or a few days out of every season, or even, as some people do, a few years out of a life in order to sit still long enough to find out what moves you most, to recall where your truest happiness lies and to remember that sometimes making a living and making a life point in opposite directions.

Then a few moments later, him saying:

And of course, this is what wise beings through the centuries from every tradition have been telling us. It’s an old idea. More than 2,000 years ago, the Stoics were reminding us it’s not our experience that makes our lives, it’s what we do with it.

….

And this has certainly been my experience as a traveler. Twenty-four years ago I took the most mind-bending trip across North Korea. But the trip lasted a few days. What I’ve done with it sitting still, going back to it in my head, trying to understand it, finding a place for it in my thinking, that’s lasted 24 years already and will probably last a lifetime. The trip, in other words, gave me some amazing sights, but it’s only sitting still that allows me to turn those into lasting insights. And I sometimes think that so much of our life takes place inside our heads, in memory or imagination or interpretation or speculation, that if I really want to change my life I might best begin by changing my mind.

Emails, ‘smartphones’, telephone handsets all around the house, television, junk mail on an almost daily basis, advertising in all its many forms, always lists of things to do; and on and on. It’s as if in this modern life, with the so many wonderful ways of doing stuff, connecting, being entertained, and more, that we have forgotten how to do the most basic and fundamental of things: Nothing! It’s as if so many of us have lost sight of the greatest luxury of all: immersing ourselves in that empty space of doing nothing.

Thus it wouldn’t be surprising to learn that more and more people are taking conscious and deliberate measures to open up a space inside their lives. Whether it is something as simple as listening to some music just before they go to sleep, because those that do notice that they sleep much better and wake up much refreshed, or taking technology ‘holidays’ during the week, or attending Yoga classes or enrolling on a course to learn Transcendental Meditation, there is a growing awareness that something in us is crying out for the sense of intimacy and depth that we get from people who take the time and trouble to sit still, to go nowhere.

Even science supports the benefits of slowing down the brain. In an article[1] posted on the Big Think blogsite, author Steven Kottler explains what are called ‘flow states’: “a person in flow obtains the ability to keenly hone their focus on the task at hand so that everything else disappears.”

Elaborating in the next paragraph, as follows:

“So our sense of self, our sense of self-consciousness, they vanish. Time dilates which means sometimes it slows down. You get that freeze frame effect familiar to any of you who have seen The Matrix or been in a car crash. Sometimes it speeds up and five hours will pass by in like five minutes. And throughout all aspects of performance, mental and physical, go through the roof.”

The part of our brain known as the prefrontal cortex houses our higher cognitive functions such as our sense of morality, our sense of will, and our sense of self. It is also that part of our brain that calculates time. When we experience flow states or what is technically known as ‘transient hypofrontality’, we lose track of time, lose our grip on assessing the past, present, and future. As Kotler explains it, “we’re plunged into what researchers call the deep now.”

Steven Kotler then goes on to say:

“So what causes transient hypofrontality? It was once assumed that flow states are an affliction reserved only for schizophrenics and drug addicts, but in the early 2000s a researcher named Aaron Dietrich realized that transient hypofrontality underpins every altered state — from dreaming to mindfulness to psychedelic trips and everything in between. Sometimes these altered states involve other parts of the brain shutting down. For example, when the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex disconnects, your sense of self-doubt and the brain’s inner critic get silenced. This results in boosted states of confidence and creativity.”

Don’t worry about the technical terms, just go back and re-read those last two sentences, “For example, when the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex disconnects, your sense of self-doubt and the brain’s inner critic get silenced. This results in boosted states of confidence and creativity.”

All from stillness!

Back to Pico Iyer’s talk and his concluding words:

So, in an age of acceleration, nothing can be more exhilarating than going slow. And in an age of distraction, nothing is so luxurious as paying attention. And in an age of constant movement, nothing is so urgent as sitting still. So you can go on your next vacation to Paris or Hawaii, or New Orleans; I bet you’ll have a wonderful time. But, if you want to come back home alive and full of fresh hope, in love with the world, I think you might want to try considering going nowhere. Thank you.

At the start of this chapter, I mentioned that I would leave it until the end to explain why I deliberately made this one on stillness the last one in the series of dog qualities we humans have to learn.

Here’s why. For the fundamental reason that it is only through the stillness of mind, the stillness of mind that we so beautifully experience when we hug our dog, or close our eyes and bury our face in our dog’s warm fur; it is that stillness of mind, that like any profound spiritual experience, that has the power to transform our mind from negative to positive, from disturbed to peaceful, from unhappy to happy.

The power of overcoming negative minds and cultivating constructive thoughts, of experiencing transforming meditations is right next to us in the souls of our dogs.

“Sanctuary is where you go to cherish your life. It’s where you practice being present. And it may not be that many steps from where you are, right now.” The Rev. Terry Hershey.

1,523 words. Copyright © 2014 Paul Handover

[1] http://bigthink.com/think-tank/steven-kotler-flow-states