Dogs and humans go back a long, long way!

We like to think of our relationship with dogs as a moderately recent affair. Not the time since dogs and humans have mixed together, that was a very long time ago, but having a dog as a pet.

But even that view needs to be updated.

Try 4,000 years ago!

ooOOoo

New Study Looks at Why Neolithic Humans Buried Their Dogs With Them 4,000 Years Ago

Analysis of the remains of 26 dogs found near Barcelona suggest the dogs had a close relationship with ancient humans

SMITHSONIAN.COM

FEBRUARY 14, 2019

Humans have enjoyed a long history of canine companions. Even if it’s unclear exactly when dogs were first domesticated (and it may have happened more than once), archaeology offers some clues as to the nature of their relationship with humans.

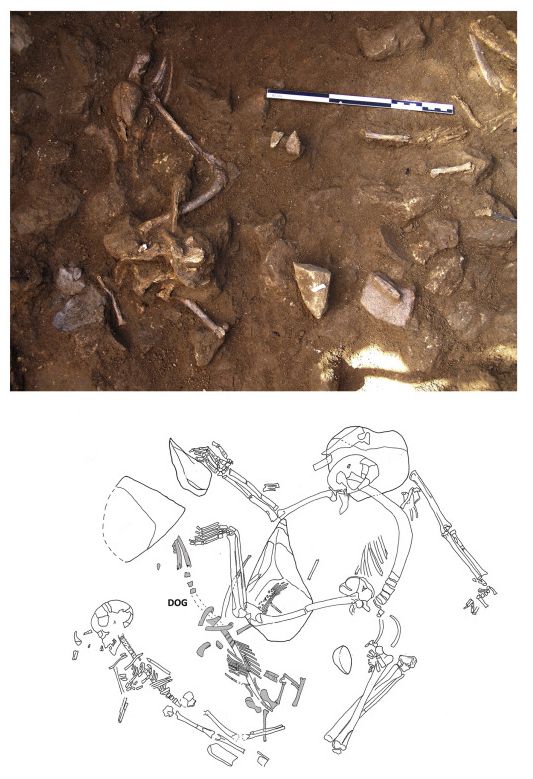

The latest clue suggests that humans living in Southern Europe between 3,600 to 4,200 years ago cared for dogs enough to regularly share their gravesites with them. Barcelona-based researchers studied the remains of 26 dogs from four different archaeological sites on the northeastern Iberian Peninsula.

The dogs ranged in age from one month to six years old. Nearly all were buried in graves with or nearby humans. “The fact that these were buried near humans suggests there was an intention and a direct relation with death and the funerary ritual”, says lead author Silvia Albizuri, a zooarchaeologist with the University of Barcelona, in a press release.

To better understand the dogs’ relationship with the humans they joined in the grave, Albizuri and her colleagues analyzed isotopes in the bones. Studying isotopes—variants of the same chemical element with different numbers of neutrons, one of the building blocks of atoms—can reveal clues about diet because molecules from plants and animals come with different ratios of various isotopes. The analysis showed that very few of the dogs ate primarily meat-based diets. Most enjoyed a diet similar to humans, consuming grains like wheat as well as animal protein. Only in two puppies and two adult dogs did the samples suggest the diet was mainly vegetarian.

This indicates that the dogs lived on food fed to them by humans, the team reports in the Journal of Archaeological Science. “These data show a close coexistence between dogs and humans, and probably, a specific preparation of their nutrition, which is clear in the cases of a diet based on vegetables,” says study co-author Eulàlia Subirà, a biological anthropologist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

The archaeological sites all belong to people of the Yamnaya Culture, or Pit Grave Culture. These nomadic people swept into Europe from the steppes north of the Black and Caspian Seas. They kept cattle for milk production and sheep and spoke a language that linguists suspect gave rise to most of the languages spoken today in Europe and Asia as far as northern India.

The buried dogs aren’t the oldest found in a human grave. That distinction belongs to a puppy found in a 14,000-year-old grave in modern-day Germany. The care given to that puppy to nurse it through illness was particularly intriguing to the researchers who discovered it. “At least some Paleolithic humans regarded some of their dogs not merely materialistically, in terms of their utilitarian value, but already had a strong emotional bond with these animals,” Liane Giemsch, co-author on a paper about the discovery and curator at the Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt, told Mary Bates at National Geographic in 2018.

The fact that the researchers in the new study found so many dogs in the region they studied indicates that the practice of burying dogs with humans was common at the time, the late Copper Age through the early Bronze Age. Perhaps the canine companions helped herd or guard livestock. What is certain is that ancient humans found the animals to be important enough to stay close to even in death.

ooOOoo

That last sentence is precious. “What is certain is that ancient humans found the animals to be important enough to stay close to even in death.”

As far back as 14,000 years!