We live on a profoundly ancient and beautiful planet.

I follow the photographic website Ugly Hedgehog and have been doing for some time. There has been a post recently from the section Photo Gallery and ‘greymule’ from Colorado called his entry ‘A Couple of Desert Scenes’ and I will display just one of his images from that post.

It makes a wonderful connection to today’s post which is from The Conversation.

ooOOoo

Evidence from Snowball Earth found in ancient rocks on Colorado’s Pikes Peak – it’s a missing link

Liam Courtney-Davies, University of Colorado Boulder; Christine Siddoway, Colorado College, and Rebecca Flowers, University of Colorado Boulder

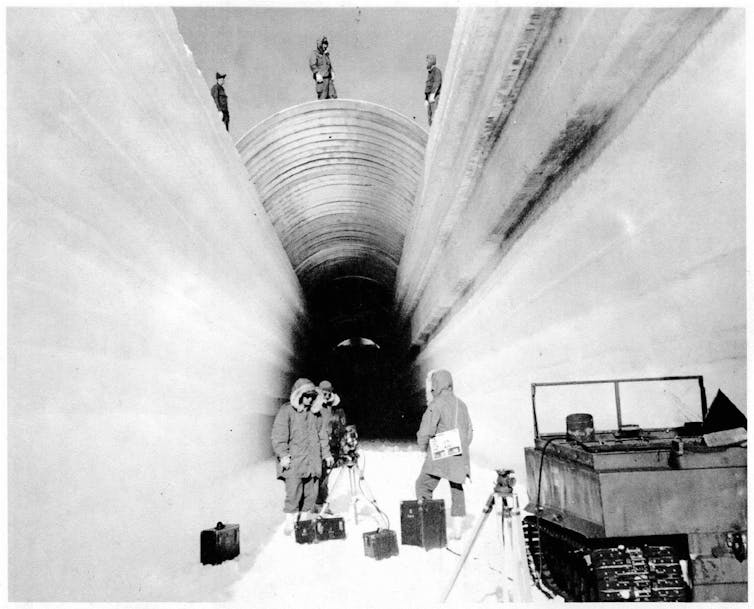

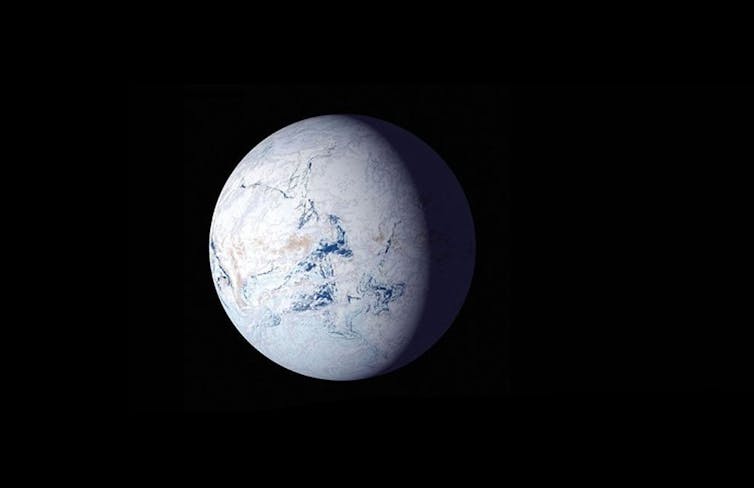

Around 700 million years ago, the Earth cooled so much that scientists believe massive ice sheets encased the entire planet like a giant snowball. This global deep freeze, known as Snowball Earth, endured for tens of millions of years.

Yet, miraculously, early life not only held on, but thrived. When the ice melted and the ground thawed, complex multicellular life emerged, eventually leading to life-forms we recognize today.

The Snowball Earth hypothesis has been largely based on evidence from sedimentary rocks exposed in areas that once were along coastlines and shallow seas, as well as climate modeling. Physical evidence that ice sheets covered the interior of continents in warm equatorial regions had eluded scientists – until now.

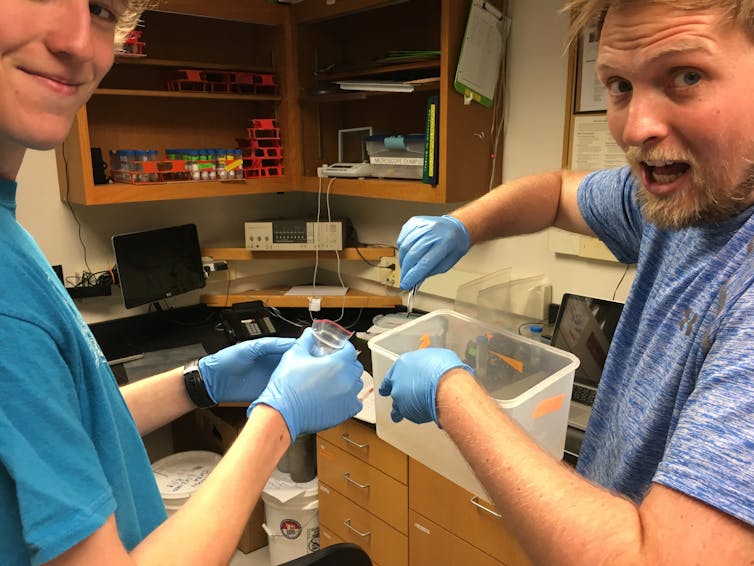

In new research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, our team of geologists describes the missing link, found in an unusual pebbly sandstone encapsulated within the granite that forms Colorado’s Pikes Peak.

Solving a Snowball Earth mystery on a mountain

Pikes Peak, originally named Tavá Kaa-vi by the Ute people, lends its ancestral name, Tava, to these notable rocks. They are composed of solidified sand injectites, which formed in a similar manner to a medical injection when sand-rich fluid was forced into underlying rock.

A possible explanation for what created these enigmatic sandstones is the immense pressure of an overlying Snowball Earth ice sheet forcing sediment mixed with meltwater into weakened rock below.

An obstacle for testing this idea, however, has been the lack of an age for the rocks to reveal when the right geological circumstances existed for sand injection.

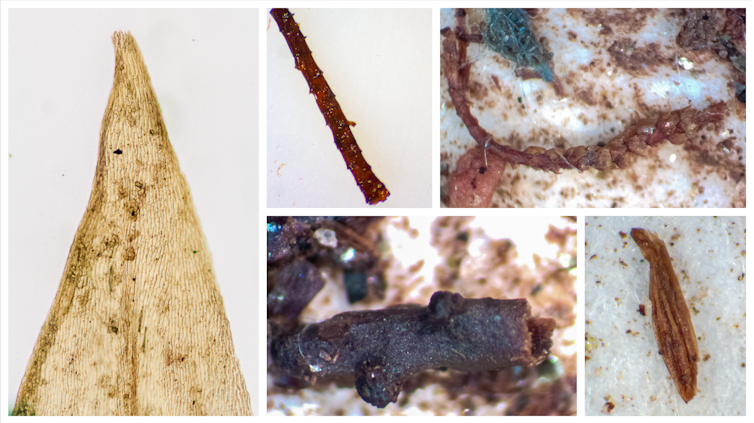

We found a way to solve that mystery, using veins of iron found alongside the Tava injectites, near Pikes Peak and elsewhere in Colorado.

Iron minerals contain very low amounts of naturally occurring radioactive elements, including uranium, which slowly decays to the element lead at a known rate. Recent advancements in laser-based radiometric dating allowed us to measure the ratio of uranium to lead isotopes in the iron oxide mineral hematite to reveal how long ago the individual crystals formed.

The iron veins appear to have formed both before and after the sand was injected into the Colorado bedrock: We found veins of hematite and quartz that both cut through Tava dikes and were crosscut by Tava dikes. That allowed us to figure out an age bracket for the sand injectites, which must have formed between 690 million and 660 million years ago.

So, what happened?

The time frame means these sandstones formed during the Cryogenian Period, from 720 million to 635 million years ago. The name is derived from “cold birth” in ancient Greek and is synonymous with climate upheaval and disruption of life on our planet – including Snowball Earth.

While the triggers for the extreme cold at that time are debated, prevailing theories involve changes in tectonic plate activity, including the release of particles into the atmosphere that reflected sunlight away from Earth. Eventually, a buildup of carbon dioxide from volcanic outgassing may have warmed the planet again.

University of Exeter professor Timothy Lenton explains why the Earth was able to freeze over.

The Tava found on Pikes Peak would have formed close to the equator within the heart of an ancient continent named Laurentia, which gradually over time and long tectonic cycles moved into its current northerly position in North America today.

The origin of Tava rocks has been debated for over 125 years, but the new technology allowed us to conclusively link them to the Cryogenian Snowball Earth period for the first time.

The scenario we envision for how the sand injection happened looks something like this:

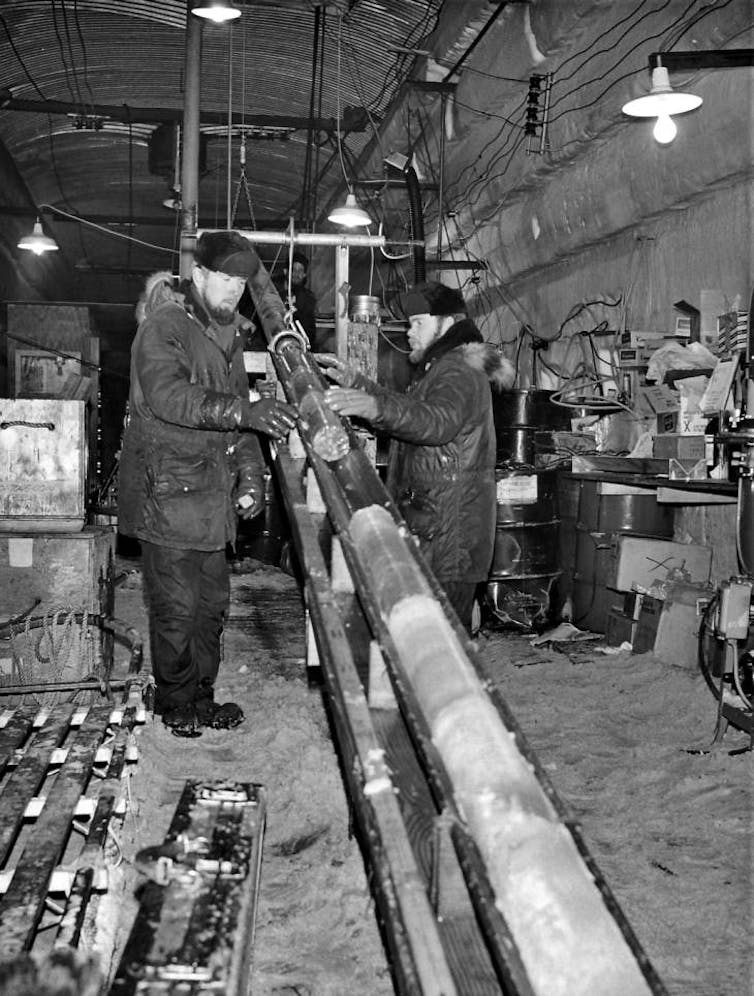

A giant ice sheet with areas of geothermal heating at its base produced meltwater, which mixed with quartz-rich sediment below. The weight of the ice sheet created immense pressures that forced this sandy fluid into bedrock that had already been weakened over millions of years. Similar to fracking for natural gas or oil today, the pressure cracked the rocks and pushed the sandy meltwater in, eventually creating the injectites we see today.

Clues to another geologic puzzle

Not only do the new findings further cement the global Snowball Earth hypothesis, but the presence of Tava injectites within weak, fractured rocks once overridden by ice sheets provides clues about other geologic phenomena.

Time gaps in the rock record created through erosion and referred to as unconformities can be seen today across the United States, most famously at the Grand Canyon, where in places, over a billion years of time is missing. Unconformities occur when a sustained period of erosion removes and prevents newer layers of rock from forming, leaving an unconformable contact.

Our results support that a Great Unconformity near Pikes Peak must have been formed prior to Cryogenian Snowball Earth. That’s at odds with hypotheses that attribute the formation of the Great Unconformity to large-scale erosion by Snowball Earth ice sheets themselves.

We hope the secrets of these elusive Cryogenian rocks in Colorado will lead to the discovery of further terrestrial records of Snowball Earth. Such findings can help develop a clearer picture of our planet during climate extremes and the processes that led to the habitable planet we live on today.

Liam Courtney-Davies, Postdoctoral Research Associate in Geological Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder; Christine Siddoway, Professor of Geology, Colorado College, and Rebecca Flowers, Professor of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

All I can add is fascinating.