A wonderful investment in studying America’s ecology is just starting.

I am indebted to The Economist for including in their issue of the 25th August a story about NEON, something I had previously not heard about.

It was then an easy step to locate the main website for the National Ecological Observatory Network, or NEON. (Just an aside that I can’t resist – NEON is such a fabulous acronym that one wonders how much push and shove there was to come up with the full name that also fitted the word ‘NEON’! Sorry, it’s just me!)

Anyway, back to the plot. The following video gives a very good idea of the projects aims. When I watched it, I found it inspiring because it seemed a solid example of how the nation, that is the USA, is starting to recognise that evolving to a new, sustainable way of life has to be built on good science. NEON strikes me as excellent science. You watch the video and see if you come to the same conclusion.

There’s also a comprehensive introduction to the project from which I will republish this,

In an era of dramatic changes in land use and other human activities, we must understand how the biosphere – the living part of earth – is changing in response to human activities. Humans depend on a diverse set of biosphere services and products, including air, water, food, fiber, and fuel. Enhancements or disruptions of these services could alter the quality of human life in many parts of the world.

To help us understand how we can maintain our quality of life on this planet, we must develop a more holistic understanding of how biosphere services and products are interlinked with human impacts. This cannot be investigated using disconnected studies on individual sites or over short periods of observation. Further, existing monitoring programs that collect data to meet natural resource management objectives are not designed to address climate change and other new, complex environmental challenges.

NEON, the first continental-scale ecological observatory, will provide comprehensive data that will allow scientists to address these issues.

Later on there’s more detail, as follows,

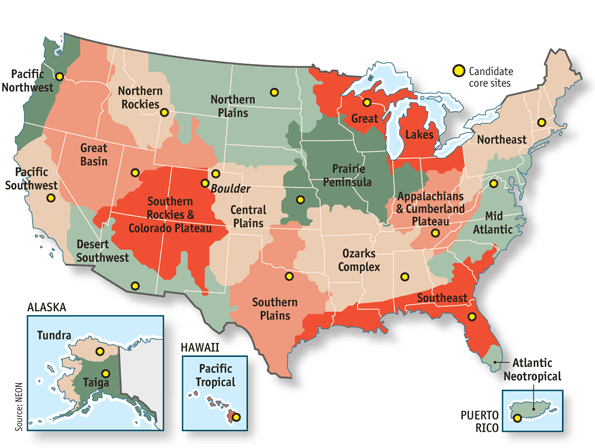

NEON has partitioned the U. S. into 20 eco-climatic domains, each of which represents different regions of vegetation, landforms, climate, and ecosystem performance. In those domains, NEON will collect site-based data about climate and atmosphere, soils and streams and ponds, and a variety of organisms. Additionally, NEON will provide a wealth of regional and national-scale data from airborne observationsand geographical data collected by Federal agencies and processed by NEON to be accessible and useful to the ecological research community. NEON will also manage a long-term multi-site stream experiment and provide a platform for future observations and experiments proposed by the scientific community.

The data collected and generated across NEON’s network – all day, every day, over a period of 30 years — will be synthesized into information products that can be used to describe changes in the nation’s ecosystem through space and time. It will be readily available in many formats to scientists, educators, students, decision makers and the general public.

For some reason I couldn’t find on the NEON website the informative map that was included in The Economist so I grabbed that one, and offer it below:

These eco-climatic domains are fully described here on the NEON website.

The benefits of this fabulous project are described thus, “The data NEON collects and provides will focus on how land use change, climate change and invasive species affect the structure and function of our ecosystems. Obtaining this kind of data over a long-term period is crucial to improving ecological forecast models. The Observatory will enable a virtual network of researchers and environmental managers to collaborate, coordinate research, and address ecological challenges at regional, national and continental scales by providing comparable information across sites and regions.”

As they say in business, if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it! So reading in the above the sentence, ‘Obtaining this kind of data over a long-term period is crucial to improving ecological forecast models.‘ is cheering to the soul.

The United States quite rightly gets a huge bashing over it CO2 emissions but to condemn the USA for that and not to applaud this sort of wonderful research is utterly unjustified. As I have hinted before, America has, more than any other country in the world, the energy to make things better over the coming years.

As Professor Sir Robert Watson highlighted here recently said, ‘… deep cuts in CO2 emissions are possible using innovative technologies without harming economic recovery.’

Amen to that!