The power of serendipity!

Why the choice of this sub-heading? Well, just because a number of quite separate articles and essays have come together to offer a powerful, cohesive argument for reconsidering the role of Nature in the future of mankind.

Of course, my use of words in that preceding sentence is completely ludicrous; the suggestion that ‘Nature’ is disconnected from ‘mankind’. Yet millions of us, to a greater or lesser degree, do behave as if we are the masters of the world.

So let me dip into what has been ‘crossing my desk’ in recent times.

On May 28th, George Monbiot published in The Guardian newspaper an essay entitled A Manifesto for Rewilding the World. (The link takes you to the article on the Monbiot blogsite.) Here’s how that essay opened,

Until modern humans arrived, every continent except Antarctica possessed a megafauna. In the Americas, alongside mastodons, mammoths, four-tusked and spiral-tusked elephants, there was a beaver the size of a black bear: eight feet from nose to tail(1). There were giant bison weighing two tonnes, which carried horns seven feet across(2).

The short-faced bear stood thirteen feet in its hind socks(3). One hypothesis maintains that its astonishing size and shocking armoury of teeth and claws are the hallmarks of a specialist scavenger: it specialised in driving giant lions and sabretooth cats off their prey(4). The Argentine roc (Argentavis magnificens) had a wingspan of 26 feet(5). Sabretooth salmon nine feet long migrated up Pacific coast rivers(6).

During the previous interglacial period, Britain and Europe contained much of the megafauna we now associate with the tropics: forest elephants, rhinos, hippos, lions and hyaenas. The elephants, rhinos and hippos were driven into southern Europe by the ice, then exterminated around 40,000 years ago when modern humans arrived(7,8,9). Lions and hyaenas persisted: lions hunted reindeer across the frozen wastes of Britain until 11,000 years ago(10, 11). The distribution of these animals has little to do with temperature: only where they co-evolved with humans and learnt to fear them did they survive.

I’m not going to reproduce the bulk of the article; just hoped that I have tickled your curiousity sufficient for you to read it in full here. But will just show you how it closed:

Despite the best efforts of governments, farmers and conservationists, nature is already beginning to return. One estimate suggests that two thirds of the previously-forested parts of the US have reforested, as farming and logging have retreated, especially from the eastern half of the country(23). Another proposes that by 2030 farmers on the European Continent (though not in Britain, where no major shift is expected) will vacate around 30 million hectares (75 million acres), roughly the size of Poland(24). While the mesofauna is already beginning to spread back across Europe, land areas of this size could perhaps permit the reintroduction of some of our lost megafauna. Why should Europe not have a Serengeti or two?

Above all, rewilding offers a positive environmentalism. Environmentalists have long known what they are against; now we can explain what we are for. It introduces hope where hope seemed absent. It offers us a chance to replace our silent spring with a raucous summer.

Then further research for this post brought to light an interview with David Suzuki in February. Widely reported, I picked the version published on Straight.com, from which comes:

In December, Canadian specialty TV channel Business News Network interviewed me about the climate summit in Copenhagen. My six-minute interview followed a five-minute live report from Copenhagen, about poor countries demanding more money to address climate change and rich countries pleading a lack of resources. Before and after those spots were all kinds of reports on the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the price of gold and the loonie, and the implications of some new phone technology.

For me, this brought into sharp focus the inevitable failure of our negotiating efforts on climate change. BNN, like the New York-based Bloomberg channel, is a 24-hour-a-day network focused completely on business. These networks indicate that the economy is our top priority. And at Copenhagen, money dominated the discussions and the outcome.

But where is the 24-hour network dealing with the biosphere? As biological creatures, we depend on clean air, clean water, clean soil, clean energy, and biodiversity for our well-being and survival. Surely protecting those fundamental needs should be our top priority and should dominate our thinking and the way we live. After all, we are animals and our biological dependence on the biosphere for our most basic needs should be obvious.

The economy is a human construct, not a force of nature like entropy, gravity, or the speed of light or our biological makeup. It makes no sense to elevate the economy above the things that keep us alive. But that’s what our prime minister does when he claims we can’t even try to meet the Kyoto targets because that might have a detrimental effect on the economy.

This economic system is built on exploiting raw materials from the biosphere and dumping the waste back into the biosphere. And conventional economics dismisses all the “services” that nature performs to keep the planet habitable for animals like us as “externalities”. As long as economic considerations trump all other factors in our decisions, we will never work our way out of the problems we’ve created.

Concluding:

Nature is our home. Nature provides our most fundamental needs. Nature dictates limits. If we are striving for a truly sustainable future, we have to subordinate our activities to the limits that come from nature. We know how much carbon dioxide can be reabsorbed by all the green things in the oceans and on land, and we know we are exceeding those limits. That’s why carbon is building up in the atmosphere. So our goal is clear. All of humanity must find a way to keep emissions below the limits imposed by the biosphere.

The only equitable course is to determine the acceptable level of emissions on a global per capita basis. Those who fall below the line should be compensated for their small carbon footprint while those who are far above should be assessed accordingly. But the economy must be aligned with the limits imposed by the biosphere, not above them.

Quite clearly, if we continue to turn our backs on Nature, the consequences won’t be long in tapping us on the shoulder.

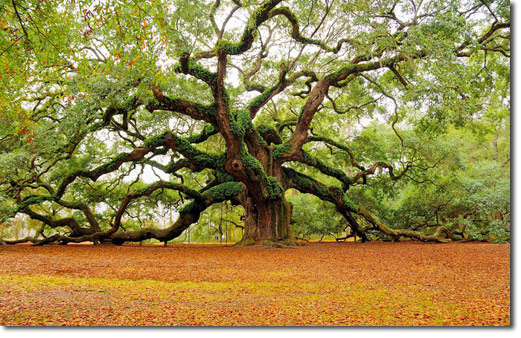

So, going to close it today with this, seen nearly a month ago on the PRI website:

oooo

Plant a Tree

Trees — by Kristof Nordin May 27, 2013

Imagine the type of world we could see

If instead of saying ‘pray,’ we said, ‘plant a tree’.

With this one little change so much more could be done

To protect all living things found under the sun.

We could ‘plant a tree’ for our troops sent away into war

So when they return they’d come home to find more.

We could ‘plant a tree’ at our churches with our husband or wife

To praise the Creator through a celebration of life.

We could ‘plant a tree’ for the needy and for those with no food

We could even plant in public without seeming rude.

The government would not have to introduce rules,

And most likely we could ‘plant a tree’ at our schools.

If we took it to task to ‘plant trees’ for the poorest,

We would all soon be reaping the wealth of a forest.

We could plant freely with those of all religions and creeds,

The improvement of earth would be based on these deeds.

We could plant with our neighbours, our family, and friends,

And ‘plant a tree’ with our enemies to help make amends.

If we ‘plant a tree’ for the sick to show them we care,

We would also be healing the soil, water, and air.

We could ‘plant a tree’ to observe when two people wed,

And plant one with our kids each night before bed.

Throughout the history of the whole human race

We find respect for the ‘tree’ has always had a place.

The great Ash of the Norse was their tree of the World,

And on a tree in the Garden is where the serpent once curled.

It was in groves of Oaks that the Druid priests wandered,

And under the Bodhi where the great Buddha pondered.

In the Bible it’s clear that we have all that we need:

‘All the trees with their fruits and plants yielding seed’.

Despite all these lessons that the past has taught

Now days, it seems, we cut our trees without thought.

This is confirmed by the Koran, for in it we read:

‘Many are the marvels of earth, yet we pay them no heed’.

We all have a duty, no matter what nation

To perform our part in protecting Creation.

Just think what we’d have if we had picked up a spade

Every time each one of us bowed our heads and prayed.

Further Reading:

oooOOOooo

The theme continues tomorrow.