Yet another stunningly powerful essay on TomDispatch.

Introduction

I do hope that as a result of Tom Engelhardt giving me written blanket permission to republish essays that appear on TomDispatch, for which I am ever grateful, many readers have gone across to the TomDispatch website and, consequently, quite a few of you have subscribed. The regular flow of essays from major names across the many fields of life is impressive.

Plus I want to harp back to a theme that I touched on during my introduction to Dianne Gray’s guest post on the 25th last, Dogs and life. That is that the vision of Learning from Dogs is to remind all of us that we have no option in terms of the long-term viability of our species than to acknowledge the power of integrity, so beautifully illustrated by our closest animal companion for tens of thousands of years, the domestic dog.

So with that in mind, settle back and read,

Tomgram: William deBuys, The West in Flames

Posted by William deBuys at 9:20AM, July 24, 2012

[Note for TomDispatch Readers: Check out my hour on Media Matters with Bob McChesney on Sunday, where he and I talked about the militarization of the U.S. and of American foreign policy, and I discussed my latest book, The United States of Fear, as well as the one I co-authored with Nick Turse, Terminator Planet: The First History of Drone Warfare, 2001-2050. Tom]

The water supply was available only an hour a day and falling. People — those who hadn’t moved north to cooler climes — were dying from the heat. Food was growing ever scarcer and the temperature soaring so that, as one reporter put it, you could “cook eggs on your sidewalk and cook soup in the oceans.” The year was 1961 and I was “there,” watching “The Midnight Sun,” a Twilight Zone episode in which the Earth was coming ever closer to the sun. (As it was The Twilight Zone, you knew there would be a twist at the end: in this case, you were inside the fevered dreams of a sick woman on a planet heading away from the sun and growing ever colder.)

In 1961, an ever-hotter planet was a sci-fi fantasy and the stuff of entertainment. No longer. Now, it’s the plot line for our planet and it isn’t entertaining at all. Just over a half-century later, we are experiencing, writes Bill McKibben in Rolling Stone, “the 327th consecutive month in which the temperature of the entire globe exceeded the 20th-century average, the odds of which occurring by simple chance were 3.7 x 10-99, a number considerably larger than the number of stars in the universe.”

Speaking personally, this summer, living through a staggering heat wave on the East coast (as in much of the rest of the country), I’ve felt a little like I’m in that fevered dream from The Twilight Zone, and a map of a deep-seated drought across 56% of the country and still spreading gives you a feeling for just why. Never in my life have I thought of the sun as implacable, but that’s changing, too. After all, the first six months of 2012 in the U.S. were 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit above the long-term norm and Colorado, swept by wildfires, was a staggering 6.4 degrees higher than the usual. TomDispatch regular William deBuys, author of A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest, catches the feel of living in a West that’s aflame and drying out fast. (To catch Timothy MacBain’s latest Tomcast audio interview in which deBuys discusses where heat, fire, and climate change are taking us, click here or download it to your iPod here.) Tom

oooOOOooo

The Oxygen Planet Struts Its Stuff

Not a “Perfect Storm” But the New Norm in the American West

By William deBuysDire fire conditions, like the inferno of heat, turbulence, and fuel that recently turned 346 homes in Colorado Springs to ash, are now common in the West. A lethal combination of drought, insect plagues, windstorms, and legions of dead, dying, or stressed-out trees constitute what some pundits are calling wildfire’s “perfect storm.”

They are only half right.

This summer’s conditions may indeed be perfect for fire in the Southwest and West, but if you think of it as a “storm,” perfect or otherwise — that is, sudden, violent, and temporary — then you don’t understand what’s happening in this country or on this planet. Look at those 346 burnt homes again, or at the High Park fire that ate 87,284 acres and 259 homes west of Fort Collins, or at the Whitewater Baldy Complex fire in New Mexico that began in mid-May, consumed almost 300,000 acres, and is still smoldering, and what you have is evidence of the new normal in the American West.

For some time, climatologists have been warning us that much of the West is on the verge of downshifting to a new, perilous level of aridity. Droughts like those that shaped the Dust Bowl in the 1930s and the even drier 1950s will soon be “the new climatology” of the region — not passing phenomena but terrifying business-as-usual weather. Western forests already show the effects of this transformation.

If you surf the blogosphere looking for fire information, pretty quickly you’ll notice a dust devil of “facts” blowing back and forth: big fires are four times more common than they used to be; the biggest fires are six-and-a-half times larger than the monster fires of yesteryear; and owing to a warmer climate, fires are erupting earlier in the spring and subsiding later in the fall. Nowadays, the fire season is two and a half months longer than it was 30 years ago.

All of this is hair-raisingly true. Or at least it was, until things got worse. After all, those figures don’t come from this summer’s fire disasters but from a study published in 2006 that compared then-recent fires, including the record-setting blazes of the early 2000s, with what now seem the good old days of 1970 to 1986. The data-gathering in the report, however, only ran through 2003. Since then, the western drought has intensified, and virtually every one of those recent records — for fire size, damage, and cost of suppression — has since been surpassed.

New Mexico’s Jemez Mountains are a case in point. Over the course of two weeks in 2000, the Cerro Grande fire burned 43,000 acres, destroying 400 homes in the nuclear research city of Los Alamos. At the time, to most of us living in New Mexico, Cerro Grande seemed a vision of the Apocalypse. Then, the Las Conchas fire erupted in 2011 on land adjacent to Cerro Grande’s scar and gave a master class in what the oxygen planet can do when it really struts its stuff.

The Las Conchas fire burned 43,000 acres, equaling Cerro Grande’s achievement,in its first fourteen hours. Its smoke plume rose to the stratosphere, and if the light was right, you could see within it rose-red columns of fire — combusting gases — flashing like lightning a mile or more above the land. Eventually the Las Conchas fire spread to 156,593 acres, setting a record as New Mexico’s largest fire in historic times.

It was a stunning event. Its heat was so intense that, in some of the canyons it torched, every living plant died, even to the last sprigs of grass on isolated cliff ledges. In one instance, the needles of the ponderosa pines were not consumed, but bent horizontally as though by a ferocious wind. No one really knows how those trees died, but one explanation holds that they were flash-blazed by a superheated wind, perhaps a collapsing column of fire, and that the wind, having already burned up its supply of oxygen, welded the trees by heat alone into their final posture of death.

It seemed likely that the Las Conchas record would last years, if not decades. It didn’t. This year the Whitewater Baldy fire in the southwest of the state burned an area almost twice as large.

Half Now, Half Later?

In 2007, Tom Swetnam, a fire expert and director of the laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona, gave an interview to CBS’s 60 Minutes.Asked to peer into his crystal ball, he said he thought the Southwest might lose half its existing forests to fire and insects over the several decades to come. He immediately regretted the statement. It wasn’t scientific; he couldn’t back it up; it was a shot from the hip, a WAG, a wild-ass guess.

Swetnam’s subsequent work, however, buttressed that WAG. In 2010, he and several colleagues quantified the loss of southwestern forestland from 1984 to 2008. It was a hefty 18%. They concluded that “only two more recurrences of droughts and die-offs similar or worse than the recent events” might cause total forest loss to exceed 50%. With the colossal fires of 2011 and 2012, including Arizona’s Wallow fire, which consumed more than half-a-million acres, the region is on track to reach that mark by mid-century, or sooner.

But that doesn’t mean we get to keep the other half.

In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change forecast a temperature increase of 4ºC for the Southwest over the present century. Given a faster than expected build-up of greenhouse gases (and no effective mitigation), that number looks optimistic today. Estimates vary, but let’s say our progress into the sweltering future is an increase of slightly less than 1ºC so far. That means we still have an awful long way to go. If the fires we’re seeing now are a taste of what the century will bring, imagine what the heat stress of a 4ºC increase will produce. And these numbers reflect mean temperatures. The ones to worry about are the extremes, the record highs of future heat waves. In the amped-up climate of the future, it is fair to think that the extremes will increase faster than the means.

At some point, every pine, fir, and spruce will be imperiled. If, in 2007, Swetnam was out on a limb, these days it’s likely that the limb has burned off and it’s getting ever easier to imagine the destruction of forests on a region-wide scale, however disturbing that may be.

More than scenery is at stake, more even than the stability of soils, ecosystems, and watersheds: the forests of the western United States account for 20% to 40% of total U.S. carbon sequestration. At some point, as western forests succumb to the ills of climate change, they will become a net releaser of atmospheric carbon, rather than one of the planet’s principle means of storing it.

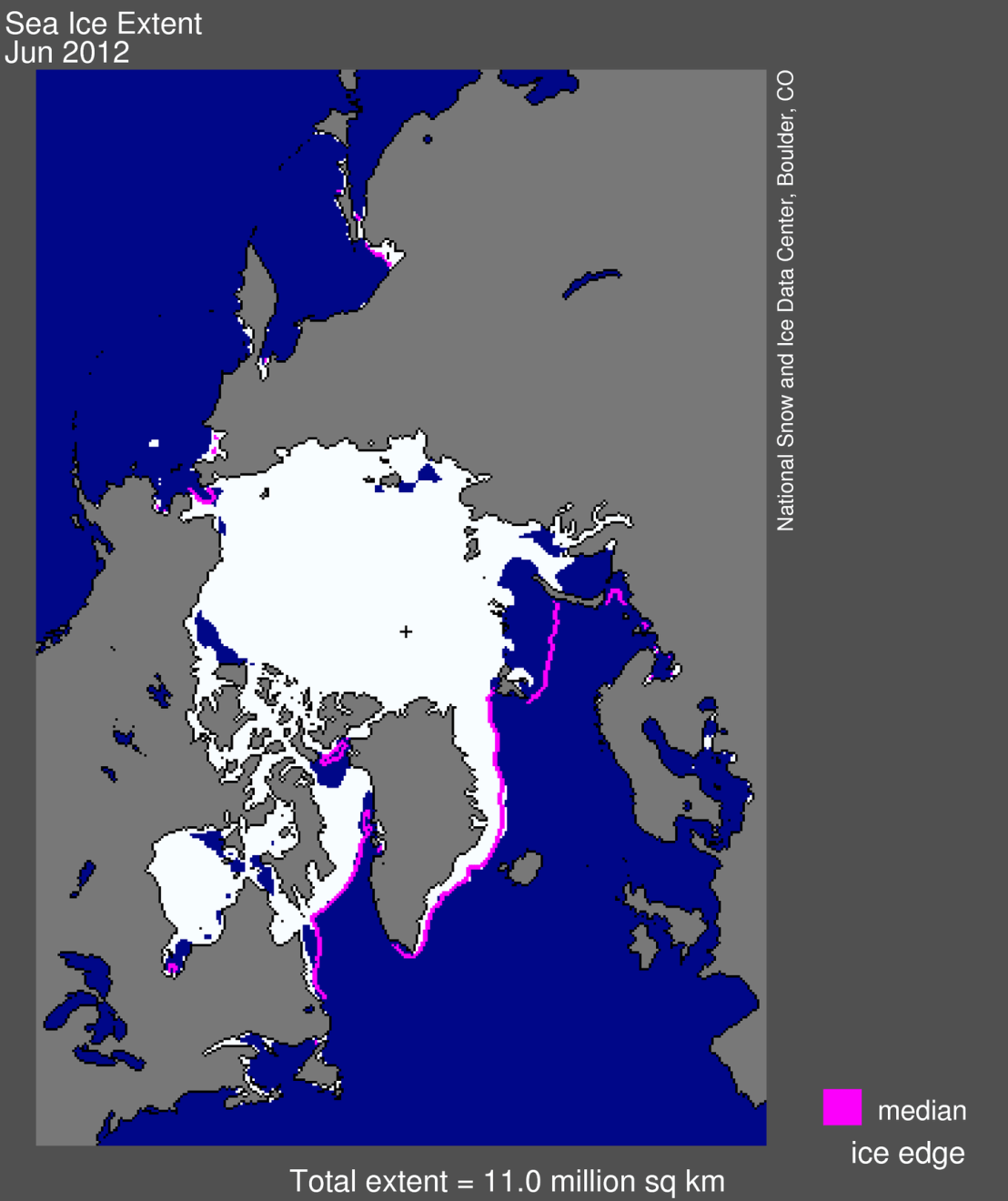

Contrary to the claims of climate deniers, the prevailing models scientists use to predict change are conservative. They fail to capture many of the feedback loops that are likely to intensify the dynamics of change. The release of methane from thawing Arctic permafrost, an especially gloomy prospect, is one of those feedbacks. The release of carbon from burning or decaying forests is another. You used to hear scientists say, “If those things happen, the consequences will be severe.” Now they more often skip that “if” and say “when” instead, but we don’t yet have good estimates of what those consequences will be.

Ways of Going

There have always been droughts, but the droughts of recent years are different from their predecessors in one significant way: they are hotter. And the droughts of the future will be hotter still.

June temperatures produced 2,284 new daily highs nationwide and tied 998 existing records. In most places, the shoe-melting heat translated into drought, and the Department of Agriculture set a record of its own recently by declaring 1,297 dried-out counties in 29 states to be “natural disaster areas.” June also closed out the warmest first half of a year and the warmest 12-month period since U.S. record keeping began in 1895. At present, 56% of the continental U.S. is experiencing drought, a figure briefly exceeded only in the 1950s.

Higher temperatures have a big impact on plants, be they a forest of trees or fields of corn and wheat. More heat means intensified evaporation and so greater water stress. In New Mexico, researchers compared the drought of the early 2000s with that of the 1950s. They found that the 1950s drought was longer and drier, but that the more recent drought caused the death of many more trees, millions of acres of them. The reason for this virulence: it was 1ºC to 1.5ºC hotter.

The researchers avoided the issue of causality by not claiming that climate changecaused the higher temperatures, but in effect stating: “If climate change is occurring, these are the impacts we would expect to see.” With this in mind, they christened the dry spell of the early 2000s a “global-change-type drought” — not a phrase that sings but one that lingers forebodingly in the mind.

No such equivocation attends a Goddard Institute for Space Studies appraisal of the heat wave that assaulted Texas, Oklahoma, and northeastern Mexico last summer. Their report represents a sea change in high-level climate studies in that they boldly assert a causal link between specific weather events and global warming. The Texas heat wave, like a similar one in Russia the previous year, was so hot that its probability of occurring under “normal” conditions (defined as those prevailing from 1951 to 1980) was approximately 0.13%. It wasn’t a 100-year heat wave or even a 500-year one; it was so colossally improbable that only changes in the underlying climate could explain it.

The decline of heat-afflicted forests is not unique to the United States. Global research suggests that in ecosystems around the world, big old trees — the giants of tropical jungles, of temperate rainforests, of systems arid and wet, hot and cold — are dying off.

More generally, when forest ecologists compare notes across continents and biomes, they find accelerating tree mortality from Zimbabwe to Alaska, Australia to Spain. The most common cause appears to be heat stress arising from climate change, along with its sidekick, drought, which often results when evaporation gets a boost.

Fire is only one cause of forest death. Heat alone can also do in a stand of trees. According to the Texas Forest Service, between 2% and 10% of all the trees in Texas, perhaps half-a-billion or so, died in last year’s heat wave, primarily from heat and desiccation. Whether you know it or not, those are staggering figures.

Insects, too, stand ready to play an ever-greater role in this onrushing disaster. Warm temperatures lengthen the growing season, and with extra weeks to reproduce, a population of bark beetles may spawn additional generations over the course of a hot summer, boosting the number of their kin that that make it to winter. Then, if the winter is warm, more larvae survive to spring, releasing ever-larger swarms to reproduce again. For as long as winters remain mild, summers long, and trees vulnerable, the beetles’ numbers will continue to grow, ultimately overwhelming the defenses of even healthy trees.

We now see this throughout the Rockies. A mountain pine beetle epidemic has decimated lodgepole pine stands from Colorado to Canada. About five million acres of Colorado’s best scenery has turned red with dead needles, a blow to tourism as well as the environment. The losses are far greater in British Columbia, where beetles have laid waste to more than 33 million forest acres, killing a volume of trees three times greater than Canada’s annual timber harvest.

Foresters there call the beetle irruption “the largest known insect infestation in North American history,” and they point to even more chilling possibilities. Until recently, the frigid climate of the Canadian Rockies prevented beetles from crossing the Continental Divide to the interior where they were, until recently, unknown. Unfortunately, warming temperatures have enabled the beetles to top the passes of the Peace River country and penetrate northern Alberta. Now a continent of jack pines lies before them, a boreal smorgasbord 3,000 miles long. If the beetles adapt effectively to their new hosts, the path is clear for them to chew their way eastward virtually to the Atlantic and to generate transformative ecological effects on a gigantic scale.

The mainstream media, prodded by recent drought declarations and other news, seem finally to be awakening to the severity of these prospects. Certainly, we should be grateful. Nevertheless, it seems a tad anticlimactic when Sam Champion, ABC News weather editor, says with this-just-in urgency to anchor Diane Sawyer, “If you want my opinion, Diane, now’s the time we start limiting manmade greenhouse gases.”

One might ask, “Why now, Sam?” Why not last year, or a decade ago, or several decades back? The news now overwhelming the West is, in truth, old news. We saw the changes coming. There should be no surprise that they have arrived.

It’s never too late to take action, but now, even if all greenhouse gas emissions were halted immediately, Earth’s climate would continue warming for at least another generation. Even if we surprise ourselves and do all the right things, the forest fires, the insect outbreaks, the heat-driven die-offs, and other sweeping transformations of the American West and the planet will continue.

One upshot will be the emergence of whole new ecologies. The landscape changes brought on by climate change are affecting areas so vast that many previous tenants of the land — ponderosa pines, for instance — cannot be expected to recolonize their former territory. Their seeds don’t normally spread far from the parent tree, and their seedlings require conditions that big, hot, open spaces don’t provide.

What will develop in their absence? What will the mountains and mesa tops of the New West look like? Already it is plain to see that scrub oak, locust, and other plants that reproduce by root suckers are prospering in places where the big pines used to stand. These plants can be burned to the ground and yet resprout vigorously a season later. One ecologist friend offers this advice, “If you have to be reincarnated as a plant in the West, try not to come back as a tree. Choose a clonal shrub, instead. The future looks good for them.”

In the meantime, forget about any sylvan dreams you might have had: this is no time to build your house in the trees.

William deBuys, a TomDispatch regular, is the author of seven books, most recently A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest (Oxford, 2011). He has long been involved in environmental affairs in the Southwest, including service as founding chairman of the Valles Caldera Trust, which administers the 87,000-acre Valles Caldera National Preserve in New Mexico. To listen to Timothy MacBain’s latest Tomcast audio interview in which deBuys discusses where heat, fire, and climate change are taking us, click here or download it to your iPod here.

Copyright 2012 William deBuys