There is more to this topic that many of us do not know.

Photons are massless. They travel at a speed that 99% of us do not really comprehend. But over to Prof. Jarred Roberts who does comprehend the subject.

ooOOoo

Do photons wear out? An astrophysicist explains light’s ability to travel vast cosmic distances without losing energy

Jarred Roberts, University of California, San Diego

My telescope, set up for astrophotography in my light-polluted San Diego backyard, was pointed at a galaxy unfathomably far from Earth. My wife, Cristina, walked up just as the first space photo streamed to my tablet. It sparkled on the screen in front of us.

“That’s the Pinwheel galaxy,” I said. The name is derived from its shape – albeit this pinwheel contains about a trillion stars.

The light from the Pinwheel traveled for 25 million years across the universe – about 150 quintillion miles – to get to my telescope.

My wife wondered: “Doesn’t light get tired during such a long journey?”

Her curiosity triggered a thought-provoking conversation about light. Ultimately, why doesn’t light wear out and lose energy over time?

Let’s talk about light

I am an astrophysicist, and one of the first things I learned in my studies is how light often behaves in ways that defy our intuitions.

Light is electromagnetic radiation: basically, an electric wave and a magnetic wave coupled together and traveling through space-time. It has no mass. That point is critical because the mass of an object, whether a speck of dust or a spaceship, limits the top speed it can travel through space.

But because light is massless, it’s able to reach the maximum speed limit in a vacuum – about 186,000 miles (300,000 kilometers) per second, or almost 6 trillion miles per year (9.6 trillion kilometers). Nothing traveling through space is faster. To put that into perspective: In the time it takes you to blink your eyes, a particle of light travels around the circumference of the Earth more than twice.

As incredibly fast as that is, space is incredibly spread out. Light from the Sun, which is 93 million miles (about 150 million kilometers) from Earth, takes just over eight minutes to reach us. In other words, the sunlight you see is eight minutes old.

Alpha Centauri, the nearest star to us after the Sun, is 26 trillion miles away (about 41 trillion kilometers). So by the time you see it in the night sky, its light is just over four years old. Or, as astronomers say, it’s four light years away. Imagine – a trip around the world at the speed of light.

With those enormous distances in mind, consider Cristina’s question: How can light travel across the universe and not slowly lose energy?

Actually, some light does lose energy. This happens when it bounces off something, such as interstellar dust, and is scattered about.

But most light just goes and goes, without colliding with anything. This is almost always the case because space is mostly empty – nothingness. So there’s nothing in the way.

When light travels unimpeded, it loses no energy. It can maintain that 186,000-mile-per-second speed forever.

It’s about time

Here’s another concept: Picture yourself as an astronaut on board the International Space Station. You’re orbiting at 17,000 miles (about 27,000 kilometers) per hour. Compared with someone on Earth, your wristwatch will tick 0.01 seconds slower over one year.

That’s an example of time dilation – time moving at different speeds under different conditions. If you’re moving really fast, or close to a large gravitational field, your clock will tick more slowly than someone moving slower than you, or who is further from a large gravitational field. To say it succinctly, time is relative.

Now consider that light is inextricably connected to time. Picture sitting on a photon, a fundamental particle of light; here, you’d experience maximum time dilation. Everyone on Earth would clock you at the speed of light, but from your reference frame, time would completely stop.

That’s because the “clocks” measuring time are in two different places going vastly different speeds: the photon moving at the speed of light, and the comparatively slowpoke speed of Earth going around the Sun.

What’s more, when you’re traveling at or close to the speed of light, the distance between where you are and where you’re going gets shorter. That is, space itself becomes more compact in the direction of motion – so the faster you can go, the shorter your journey has to be. In other words, for the photon, space gets squished.

Which brings us back to my picture of the Pinwheel galaxy. From the photon’s perspective, a star within the galaxy emitted it, and then a single pixel in my backyard camera absorbed it, at exactly the same time. Because space is squished, to the photon the journey was infinitely fast and infinitely short, a tiny fraction of a second.

But from our perspective on Earth, the photon left the galaxy 25 million years ago and traveled 25 million light years across space until it landed on my tablet in my backyard.

And there, on a cool spring night, its stunning image inspired a delightful conversation between a nerdy scientist and his curious wife.

Jarred Roberts, Project Scientist, University of California, San Diego

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

This remark jumped out at me when I first read the article: ‘In the time it takes you to blink your eyes, a particle of light travels around the circumference of the Earth more than twice.’

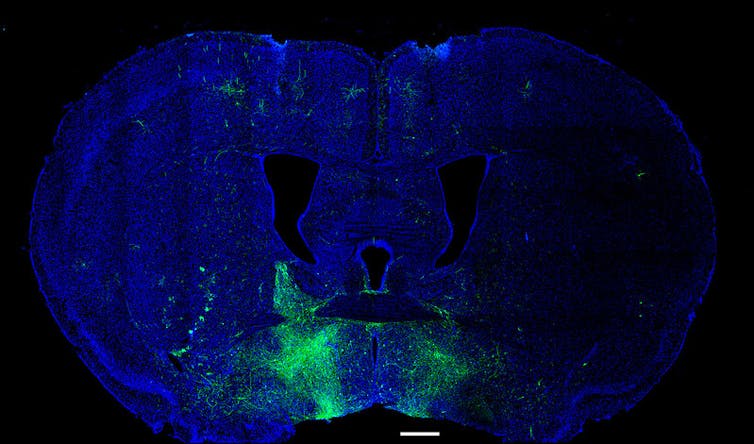

The following photograph is the Milky Way.

The image is from Geography Realm.

Despite the fact that the article is far from me understanding it, it doesn’t reduce the wonder and the awe for me of outer space.