A powerful essay by Tom Engelhardt from his blogsite TomDispatch.

Regular readers of Learning from Dogs know that essays from TomDispatch often find their way onto these pages. They are republished with the generous permission of Tom and I endeavour to select those essays that shine a new light on a current issue. No less so than with today’s essay, first published over on TomDispatch on May 22nd, 2014.

Just a note before you start reading Tom’s very important essay. That there are many links to papers, articles and other references throughout the essay. (I know, they took me a couple of hours to set up!) Could I recommend strongly that you ‘click’ on each link and make a note of the references you wish to read at a later time. I shall be referring to some of them next week when I comment more generally on this fabulous essay.

ooOOoo

Tomgram: Engelhardt, Is Climate Change a Crime Against Humanity?

The 95% Doctrine

Climate Change as a Weapon of Mass Destruction

By Tom Engelhardt

Who could forget? At the time, in the fall of 2002, there was such a drumbeat of “information” from top figures in the Bush administration about the secret Iraqi program to develop weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and so endanger the United States. And who — other than a few suckers — could have doubted that Saddam Hussein was eventually going to get a nuclear weapon? The only question, as our vice president suggested on “Meet the Press,” was: Would it take one year or five? And he wasn’t alone in his fears, since there was plenty of proof of what was going on. For starters, there were those “specially designed aluminum tubes” that the Iraqi autocrat had ordered as components for centrifuges to enrich uranium in his thriving nuclear weapons program. Reporters Judith Miller and Michael Gordon hit the front page of the New York Times with that story on September 8, 2002.

Then there were those “mushroom clouds” that Condoleezza Rice, our national security advisor, was so publicly worried about — the ones destined to rise over American cities if we didn’t do something to stop Saddam. As she fretted in a CNN interview with Wolf Blitzer on that same September 8th, “[W]e don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud.” No, indeed, and nor, it turned out, did Congress!

And just in case you weren’t anxious enough about the looming Iraqi threat, there were those unmanned aerial vehicles — Saddam’s drones! — that could be armed with chemical or biological WMD from his arsenal and flown over America’s East Coast cities with unimaginable results. President George W. Bush went on TV to talk about them and congressional votes were changed in favor of war thanks to hair-raising secret administration briefings about them on Capitol Hill.

In the end, it turned out that Saddam had no weapons program, no nuclear bomb in the offing, no centrifuges for those aluminum pipes, no biological or chemical weapons caches, and no drone aircraft to deliver his nonexistent weapons of mass destruction (nor any ships capable of putting those nonexistent robotic planes in the vicinity of the U.S. coast). But what if he had? Who wanted to take that chance? Not Vice President Dick Cheney, certainly. Inside the Bush administration he propounded something that journalist Ron Suskind later dubbed the “one percent doctrine.” Its essence was this: if there was even a 1% chance of an attack on the United States, especially involving weapons of mass destruction, it must be dealt with as if it were a 95%-100% certainty.

Here’s the curious thing: if you look back on America’s apocalyptic fears of destruction during the first 14 years of this century, they largely involved three city-busting weapons that were fantasies of Washington’s fertile imperial imagination. There was that “bomb” of Saddam’s, which provided part of the pretext for a much-desired invasion of Iraq. There was the “bomb” of the mullahs, the Iranian fundamentalist regime that we’ve just loved to hate ever since they repaid us, in 1979, for the CIA’s overthrow of an elected government in 1953 and the installation of the Shah by taking the staff of the U.S. embassy in Tehran hostage. If you believed the news from Washington and Tel Aviv, the Iranians, too, were perilously close to producing a nuclear weapon or at least repeatedly on the verge of the verge of doing so. The production of that “Iranian bomb” has, for years, been a focus of American policy in the Middle East, the “brink” beyond which war has endlessly loomed. And yet there was and is no Iranian bomb, nor evidence that the Iranians were or are on the verge of producing one.

Finally, of course, there was al-Qaeda’s bomb, the “dirty bomb” that organization might somehow assemble, transport to the U.S., and set off in an American city, or the “loose nuke,” maybe from the Pakistani arsenal, with which it might do the same. This is the third fantasy bomb that has riveted American attention in these last years, even though there is less evidence for or likelihood of its imminent existence than of the Iraqi and Iranian ones.

To sum up, the strange thing about end-of-the-world-as-we’ve-known-it scenarios from Washington, post-9/11, is this: with a single exception, they involved only non-existent weapons of mass destruction. A fourth weapon — one that existed but played a more modest role in Washington’s fantasies — was North Korea’s perfectly real bomb, which in these years the North Koreans were incapable of delivering to American shores.

The “Good News” About Climate Change

In a world in which nuclear weapons remain a crucial coin of the realm when it comes to global power, none of these examples could quite be classified as 0% dangers. Saddam had once had a nuclear program, just not in 2002-2003, and also chemical weapons, which he used against Iranian troops in his 1980s war with their country (with the help of targeting information from the U.S. military) and against his own Kurdish population. The Iranians might (or might not) have been preparing their nuclear program for a possible weapons breakout capability, and al-Qaeda certainly would not have rejected a loose nuke, if one were available (though that organization’s ability to use it would still have been questionable).

In the meantime, the giant arsenals of WMD in existence, the American, Russian, Chinese, Israeli, Pakistani, and Indian ones that might actually have left a crippled or devastated planet behind, remained largely off the American radar screen. In the case of the Indian arsenal, the Bush administration actually lent an indirect hand to its expansion. So it was twenty-first-century typical when President Obama, trying to put Russia’s recent actions in the Ukraine in perspective, said, “Russia is a regional power that is threatening some of its immediate neighbors. I continue to be much more concerned when it comes to our security with the prospect of a nuclear weapon going off in Manhattan.”

Once again, an American president was focused on a bomb that would raise a mushroom cloud over Manhattan. And which bomb, exactly, was that, Mr. President?

Of course, there was a weapon of mass destruction that could indeed do staggering damage to or someday simply drown New York City, Washington D.C., Miami, and other East coast cities. It had its own efficient delivery systems — no nonexistent drones or Islamic fanatics needed. And unlike the Iraqi, Iranian, or al-Qaeda bombs, it was guaranteed to be delivered to our shores unless preventive action was taken soon. No one needed to hunt for its secret facilities. It was a weapons system whose production plants sat in full view right here in the United States, as well as in Europe, China, and India, as well as in Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Venezuela, and other energy states.

So here’s a question I’d like any of you living in or visiting Wyoming to ask the former vice president, should you run into him in a state that’s notoriously thin on population: How would he feel about acting preventively, if instead of a 1% chance that some country with weapons of mass destruction might use them against us, there was at least a 95% — and likely as not a 100% — chance of them being set off on our soil? Let’s be conservative, since the question is being posed to a well-known neoconservative. Ask him whether he would be in favor of pursuing the 95% doctrine the way he was the 1% version.

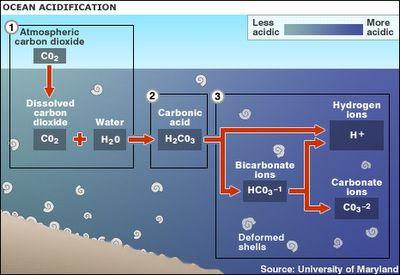

After all, thanks to a grim report in 2013 from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, we know that there is now a 95%-100% likelihood that “human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming [of the planet] since the mid-20th century.” We know as well that the warming of the planet — thanks to the fossil fuel system we live by and the greenhouse gases it deposits in the atmosphere — is already doing real damage to our world and specifically to the United States, as a recent scientific report released by the White House made clear. We also know, with grimly reasonable certainty, what kinds of damage those 95%-100% odds are likely to translate into in the decades, and even centuries, to come if nothing changes radically: a temperature rise by century’s end that could exceed 10 degrees Fahrenheit, cascading species extinctions, staggeringly severe droughts across larger parts of the planet (as in the present long-term drought in the American West and Southwest), far more severe rainfall across other areas, more intense storms causing far greater damage, devastating heat waves on a scale no one in human history has ever experienced, masses of refugees, rising global food prices, and among other catastrophes on the human agenda, rising sea levels that will drown coastal areas of the planet.

From two scientific studies just released, for example, comes the news that the West Antarctic ice sheet, one of the great ice accumulations on the planet, has now begun a process of melting and collapse that could, centuries from now, raise world sea levels by a nightmarish 10 to 13 feet. That mass of ice is, according to the lead authors of one of the studies, already in “irreversible retreat,” which means — no matter what acts are taken from now on — a future death sentence for some of the world’s great cities. (And that’s without even the melting of the Greenland ice shield, not to speak of the rest of the ice in Antarctica.)

All of this, of course, will happen mainly because we humans continue to burn fossil fuels at an unprecedented rate and so annually deposit carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at record levels. In other words, we’re talking about weapons of mass destruction of a new kind. While some of their effects are already in play, the planetary destruction that nuclear weapons could cause almost instantaneously, or at least (given “nuclear winter” scenarios) within months, will, with climate change, take decades, if not centuries, to deliver its full, devastating planetary impact.

When we speak of WMD, we usually think of weapons — nuclear, biological, or chemical — that are delivered in a measurable moment in time. Consider climate change, then, a WMD on a particularly long fuse, already lit and there for any of us to see. Unlike the feared Iranian bomb or the Pakistani arsenal, you don’t need the CIA or the NSA to ferret such “weaponry” out. From oil wells to fracking structures, deep sea drilling rigs to platforms in the Gulf of Mexico, the machinery that produces this kind of WMD and ensures that it is continuously delivered to its planetary targets is in plain sight. Powerful as it may be, destructive as it will be, those who control it have faith that, being so long developing, it can remain in the open without panicking populations or calling any kind of destruction down on them.

The companies and energy states that produce such WMD remain remarkably open about what they’re doing. Generally speaking, they don’t hesitate to make public, or even boast about, their plans for the wholesale destruction of the planet, though of course they are never described that way. Nonetheless, if an Iraqi autocrat or Iranian mullahs spoke in similar fashion about producing nuclear weapons and how they were to be used, they would be toast.

Take ExxonMobil, one of the most profitable corporations in history. In early April, it released two reports that focused on how the company, as Bill McKibben has written, “planned to deal with the fact that [it] and other oil giants have many times more carbon in their collective reserves than scientists say we can safely burn.” He went on:

The company said that government restrictions that would force it to keep its [fossil fuel] reserves in the ground were ‘highly unlikely,’ and that they would not only dig them all up and burn them, but would continue to search for more gas and oil — a search that currently consumes about $100 million of its investors’ money every single day. ‘Based on this analysis, we are confident that none of our hydrocarbon reserves are now or will become “stranded.”‘

In other words, Exxon plans to exploit whatever fossil fuel reserves it possesses to their fullest extent. Government leaders involved in supporting the production of such weapons of mass destruction and their use are often similarly open about it, even while also discussing steps to mitigate their destructive effects. Take the White House, for instance. Here was a statement President Obama proudly made in Oklahoma in March 2012 on his energy policy:

Now, under my administration, America is producing more oil today than at any time in the last eight years. That’s important to know. Over the last three years, I’ve directed my administration to open up millions of acres for gas and oil exploration across 23 different states. We’re opening up more than 75% of our potential oil resources offshore. We’ve quadrupled the number of operating rigs to a record high. We’ve added enough new oil and gas pipeline to encircle the Earth and then some.

Similarly, on May 5th, just before the White House was to reveal that grim report on climate change in America, and with a Congress incapable of passing even the most rudimentary climate legislation aimed at making the country modestly more energy efficient, senior Obama adviser John Podesta appeared in the White House briefing room to brag about the administration’s “green” energy policy. “The United States,” he said, “is now the largest producer of natural gas in the world and the largest producer of gas and oil in the world. It’s projected that the United States will continue to be the largest producer of natural gas through 2030. For six straight months now, we’ve produced more oil here at home than we’ve imported from overseas. So that’s all a good-news story.”

Good news indeed, and from Vladmir Putin’s Russia, which just expanded its vast oil and gas holdings by a Maine-sized chunk of the Black Sea off Crimea, to Chinese “carbon bombs,” to Saudi Arabian production guarantees, similar “good-news stories” are similarly promoted. In essence, the creation of ever more greenhouse gases — of, that is, the engine of our future destruction — remains a “good news” story for ruling elites on planet Earth.

Weapons of Planetary Destruction

We know exactly what Dick Cheney — ready to go to war on a 1% possibility that some country might mean us harm — would answer, if asked about acting on the 95% doctrine. Who can doubt that his response would be similar to those of the giant energy companies, which have funded so much climate-change denialism and false science over the years? He would claim that the science simply isn’t “certain” enough (though “uncertainty” can, in fact, cut two ways), that before we commit vast sums to taking on the phenomenon, we need to know far more, and that, in any case, climate-change science is driven by a political agenda.

For Cheney & Co., it seemed obvious that acting on a 1% possibility was a sensible way to go in America’s “defense” and it’s no less gospel for them that acting on at least a 95% possibility isn’t. For the Republican Party as a whole, climate-change denial is by now nothing less than a litmus test of loyalty, and so even a 101% doctrine wouldn’t do when it comes to fossil fuels and this planet.

No point, of course, in blaming this on fossil fuels or even the carbon dioxide they give off when burned. These are no more weapons of mass destruction than are uranium-235 and plutonium-239. In this case, the weaponry is the production system that’s been set up to find, extract, sell at staggering profits, and burn those fossil fuels, and so create a greenhouse-gas planet. With climate change, there is no “Little Boy” or “Fat Man” equivalent, no simple weapon to focus on. In this sense, fracking is the weapons system, as is deep-sea drilling, as are those pipelines, and the gas stations, and the coal-fueled power plants, and the millions of cars filling global roads, and the accountants of the most profitable corporations in history.

All of it — everything that brings endless fossil fuels to market, makes those fuels eminently burnable, and helps suppress the development of non-fossil fuel alternatives — is the WMD. The CEOs of the planet’s giant energy corporations are the dangerous mullahs, the true fundamentalists, of planet Earth, since they are promoting a faith in fossil fuels which is guaranteed to lead us to some version of End Times.

Perhaps we need a new category of weapons with a new acronym to focus us on the nature of our present 95%-100% circumstances. Call them weapons of planetary destruction (WPD) or weapons of planetary harm (WPH). Only two weapons systems would clearly fit such categories. One would be nuclear weapons which, even in a localized war between Pakistan and India, could create some version of “nuclear winter” in which the planet was cut off from the sun by so much smoke and soot that it would grow colder fast, experience a massive loss of crops, of growing seasons, and of life. In the case of a major exchange of such weapons, we would be talking about “the sixth extinction” of planetary history.

Though on a different and harder to grasp time-scale, the burning of fossil fuels could end in a similar fashion — with a series of “irreversible” disasters that could essentially burn us and much other life off the Earth. This system of destruction on a planetary scale, facilitated by most of the ruling and corporate elites on the planet, is becoming (to bring into play another category not usually used in connection with climate change) the ultimate “crime against humanity” and, in fact, against most living things. It is becoming a “terracide.”

Tom Engelhardt is a co-founder of the American Empire Project and author of The United States of Fear as well as a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture (from which some of this essay has been adapted). He runs the Nation Institute’s TomDispatch.com. His latest book, co-authored with Nick Turse, is Terminator Planet: The First History of Drone Warfare, 2001-2050.

Copyright 2014 Tom Engelhardt

ooOOoo

There are so many strong and fundamental points raised in this essay from Tom that I am going to return to them next week. (Will give it a rest for July 4th!)