This will take your breath away.

Yesterday, I read the latest from TomDispatch, an essay entitled Eduardo Galeano, A Lost and Found History of Lives and Dreams (Some Broken).

I wasn’t sure if I had vaguely heard of Eduardo Galeano before but whatever, I had no idea of the power and beauty of his writings and was simply blown away when reading them. As Tom introduced the writings:

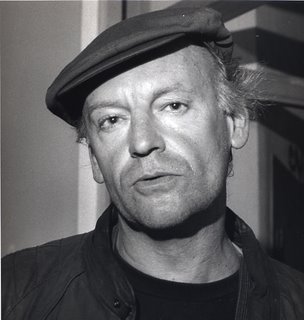

Who isn’t a fan of something — or someone? So consider this my fan’s note. To my mind, Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano is among the greats of our time. His writing has “it” — that indefinable quality you can’t describe but know as soon as you read it. He’s created a style that combines the best of journalism, history, and fiction and a form for his books that, as far as I know, has no name but involves short bursts of almost lyrical reportage, often about events long past. As it turns out, he also carries “it” with him. I was his English-language book editor years ago and can testify to that, even though on meeting him you might not initially think so. He has nothing of the showboat about him. In person, he’s almost self-effacing and yet somehow he brings out in others the urge to tell stories as they’ve never told them before.

Despite Tom’s blanket permission to republish his essays, I’m not going to do so in this case, there’s a small niggle in the back of my mind that the copyright issues are rightfully protecting Mr. Galeano’s publishing rights.

So just going to offer this single extract and trust that you will go here and read Tom’s full essay: please do!

Century of Disaster

Riddles, Lies, and Lives — from Fidel Castro and Muhammad Ali to Albert Einstein and Barbie

By Eduardo Galeano[The following passages are excerpted from Eduardo Galeano’s history of humanity, Mirrors (Nation Books).]

Walls

The Berlin Wall made the news every day. From morning till night we read, saw, heard: the Wall of Shame, the Wall of Infamy, the Iron Curtain…

In the end, a wall which deserved to fall fell. But other walls sprouted and continue sprouting across the world. Though they are much larger than the one in Berlin, we rarely hear of them.

Little is said about the wall the United States is building along the Mexican border, and less is said about the barbed-wire barriers surrounding the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla on the African coast.

Practically nothing is said about the West Bank Wall, which perpetuates the Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands and will be 15 times longer than the Berlin Wall. And nothing, nothing at all, is said about the Morocco Wall, which perpetuates the seizure of the Saharan homeland by the kingdom of Morocco, and is 60 times the length of the Berlin Wall.

Why are some walls so loud and others mute?

See what I mean!

There is much more about Eduardo Galeano on the web as these two following links prove.

Wikipedia have an entry here that is informative. Then there is an in-depth article about the man over on The Atlantic website, that starts thus:

Eduardo Galeano is regarded as one of Latin America’s fiercest voices of social conscience. Yet he insists that language — its secrets, mysteries, and masks — always comes first.

November 30, 2000

“The division of labor among nations,” Eduardo Galeano proclaimed in the opening sentence of Open Veins of Latin America, “is that some specialize in winning and others in losing.” A native of Uruguay who was forced into exile under the country’s military regime during the 1970s, Galeano has always identified with the losing side. Open Veins, originally published in Mexico in 1971, employed captivating, elegiac prose to chronicle five centuries of plunder and imperialism in Latin America. Radically different in style, though not in content, from Marxist-oriented “dependency theory” of the 1960s — which held that Latin America had been systematically marginalized by the world economy since the colonial era — Open Veins quickly became a canonical text in radical circles, selling hundreds of thousands of copies in the Southern Hemisphere. In a period of social upheaval, guerrilla warfare, and dictatorship, the book, composed in three months of intense labor, was routinely treated as samizdat: when Open Veins was banned by the Pinochet regime, a young woman fled Chile with the book stashed in her infant’s diapers.

Going to close by musing on the fact that in today’s visual, technological age, the sharing of words, in all ways, shapes and sizes, across so many parts of our global society, is a pure miracle. Such creativity out there!