A powerful guest post from Patrice Ayme on where next for American energy.

Introduction.

I must have spent an age musing over what to call this Post. Patrice called it simply ‘Energy Question For The USA’ and it’s a highly appropriate question. But in the end I chose the title ‘Questions are never stupid’ because I was mindful of the well-known saying, “There is no such thing as a stupid question, only a stupid answer!”

So the smart question raised by Patrice is not only very highly appropriate for 2012, it’s also a question that just has to have a smart answer. Because we are on the brink of it being too late to be flirting with stupid answers. What many scientists are saying, in one form or another, is that if we don’t embrace the journey of moving away from carbon-based sources of energy for society now and find those alternate sustainable sources by the end of this decade then the laws of unintended consequences will kick in with a vengeance. The end of the decade is eight years away!

Here’s a picture of my grandson who was one-year-old just a week ago.

That picture reminds me of the comment early on in James Hansen’s book, Storms of my Grandchildren, where he writes ‘I did not want my grandchildren, someday in the future, to look back and say, “Opa understood what was happening, but he did not make it clear.”

So on to the Guest post from Patrice. It’s not an easy, quick read but I’ll tell you what it is! It’s the sort of ‘wake-up’ call this fine Nation and this even finer Planet should be getting from countless politicians and leaders. So do read it and, even better, add your comments, and wonder why we seem so content on fiddling while Rome burns!

oooOOOooo

Energy Question For The USA

THE AGE OF OIL PRODUCED THE AMERICAN CENTURY. NOW WHAT?

No Vision, No Mission, No Energy

***

Another editorial of Paul Krugman firing volleys at republican “paranoia” for accusing Obama of driving up oil prices. As he observes in “Paranoia Strikes Deeper“: …“the president of the United States doesn’t control gasoline prices, or even have much influence over those prices. Oil prices are set in a world market, and America, which accounts for only about a tenth of world production, can’t move those prices much. Indeed, the recent rise in gas prices has taken place despite rising U.S. oil production and falling imports.”

American households tend to borrow as much as they can. Thus, when oil prices increase markedly, Americans have to cut in crucial budgets, such as house payments. I said at the time that it would lead to a peak in housing prices, and it did.

Why such a drastic influence of oil prices on the economy of the USA? Because Americans, except in a few places such as New York, commute by private car to work. So Americans have to feed the car, if they want to feed themselves.

It was not this way a century ago, or so. At the time public transportation systems using electric tramways and trains were found all over, even in Los Angeles. Car companies put an end to that outrage in the late fifties by buying, and then destroying, all the public transportation system they could put their greedy hands on. Fossil fuel plutocrats were delighted.

But let’s set aside Krugman’s fake indignation. He is smart enough to know that Romney will do what Romney needs to do to win the Obama, I mean, the election. Waxing lyrical about Romney doing as Obama, does not beat going lyrical about sunrise.

Gasoline prices in the USA are way down in real dollars to what they used to be, decades ago. And so is the gas tax. This means that, far from adapting to the gathering multiply-pronged world ecological and energy crisis, the USA has gone the other way, denying there is any crisis. “What? Me worry?” That’s got to be anti-American indeed. No, real blooded Americans are all into strip searches and the death panel at the White House.

In Europe, gas prices are more than twice that of the USA, thanks to heavy taxes (stations in France have sported two euros a liter, that is 8 euros per gallon, or more than $10.50). [UK unleaded petrol price, as of today, is the equivalent of $8.70 per gallon, Ed.]

This means that far from being down and out, Europe is efficient enough to operate at that high price level. It also means that Europe is much more motivated than the USA to get much more efficient. In other words, high gasoline prices in Europe are a safety margin. The high prices force the European free market to adapt to a situation that the free market of the USA will encounter someday. Adaptation takes decades: new energies take on the average, historically speaking, 50 years to become dominant. Same, one would guess, for energy efficiencies.

Basically, if oil prices doubled from here, gasoline prices would double in the USA. Whereas, even if the Europeans decided to keep the same high taxes, gasoline prices would only augment by 50%. And, in the much more efficient European economy, with plenty of public electric transportation available, the noxious effects on the European economy would be much less than one would expect from a 50% oil price rise.

The world gets 55 × 1018 joules of useful energy from 475 × 1018 joules of primary energy produced by fossil fuels, biomass and nuclear power plants. That tremendous inefficiency (less than 13%!) needs to be corrected. It will be, if, and only if, prices are kept high. Thus energy taxes are necessary to adapt to the looming penury.

Why looming penury? Because the reserves of other fossil fuels may have been vastly overestimated (by a factor of 5 in the case of coal). Various fossil fuel lobbies have an interest to over-estimate the reserves (because it keeps the world addicted, as they present their industry as a long range solution, which it is not).

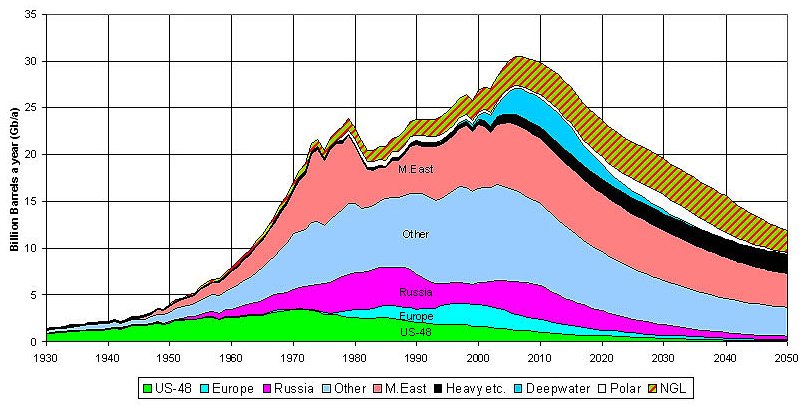

Looking at the raw production numbers, as exhibited below in the graphs, paints a completely different story: production from existing fields is going down dramatically (at 5% rate, per year). In other words we are in the treachorous waters between the catastrophe of CO2 poisoning and the disaster of running out of energy to burn.

The unavoidable rise of fuel prices will be less grave in Europe than in the USA, because many Europeans would opt for the available electric-based public transportation system (the combination of much more efficient electric motors and central generation is much more efficient than distributing oil to put in SUVs all over, as done in the USA; SUVs, because there are too many holes in the asphalt. A problem partly related to high oil prices!).

Yet, the increase of the cost of imported oil corresponds exactly to the Italian deficit ($55 billion). Although that deficit increase had many causes, oil price increase was by far the most important. And the same for other Southern European countries. So the rise of oil prices was the barrel that broke the back of European debt.

In the USA, ten out of 11 post WWII recessions were followed by oil price spikes. Why are American minds so closed up to the looming strangulation of their economy by oil? Because the fossil fuel plutocracy is on a rampage in the USA. It uses a red hot propaganda to persuade the vast American public of undifferentiated sheep that there is no CO2 ecological crisis, and no energy crisis. (Although the latest polls indicate that two thirds of the public, in a splendid turn-around, believe that there is indeed a man-made climate change crisis; never mind that the New York Times had the latest tornado rampage, with 40 dead, presented as discreetly as possible.)

Why are the fossil plutocrats hysterical? Well we are past Peak Cheap Oil. Moreover, the “majors“, the world’s largest oil companies, have been pushed out of more and more countries, and replaced by national oil companies. Desperate, the majors have gone for riskier and riskier drilling in the deep ocean. Now Chevron, and Transocean, after a 4-day leak off Brazil, see prosecutors asking for lengthy prison sentences and enormous fines.

Most of these oil companies are American, so they have pushed forfracking (destroying the underground with poisons to extract fossil fuels). Superficially, it works: USA imports of fossil fuels went quickly from 60% down to 40%.

However, that did not make a dent in the world price situation, because the demand keeps rising, but the world, overall, is PAST PEAK OIL (as I have long argued and the Nature article alluded to below confirmed, using the obvious argument found in the graphs).

So, basically, American fracking finances Chinese oil consumption. Here are some graphs extracted from Nature and the USA government:

When the horrid sun of diminishing resources rises over the parched American oil desert, while fracking reveals itself to be an unfathomable catastrophe, the howling is going to be very great, and one more reason for a depression will blossom.

Much of the USA’s superiority, in the last 150 years, has come from abundant and cheap oil. First in the North-East, then down to Oklahoma, Texas, Colorado, California. Compare with Western Europe, which had basically no oil.

Oil was not just a question of cheap, convenient energy. Oil has, short of nuclear energy, the highest energy density of any material (OK, nuclear energy is millions of time more energy dense).

Oil gave the USA enormous diplomatic and conspiratorial leverage. American oil plutocrats helped Lenin and Stalin develop their colossal fields in the Caucasus and Caspian. One of those plutocrats, Harriman, son of a railroad magnate, and brother of another Harriman, was one of the main operators of the democratic party. Let alone banker to Hitler. He was decorated both by Stalin, and by Hitler. He then went on as U.S. ambassador to major European capitals, and stayed one the main operators of the government of the USA for decades. “Democrats” have long been impure.

Interestingly, I searched the Internet for a document mentioning Harriman’s Stalino-Hitlerian decorations, but could not find it (I have seen the pictures in the past). All I could read is how much Harriman resisted Stalin each time they met, and that was all the time (a total lie that Harriman resisted Hitler, or Stalin: Harriman was an accomplice of Stalin, and helped give him half of Europe, in exchange for manganese and other stuff. But now Internet agents are obviously paid to reconstruct a truth where American plutocrats look good, knights in shining armor, fighting Stalin or Hitler, each time they met for tea, dinner, lunch, breakfast, and interminable conferences, for years on end, decade after decade).

A famous example of the clout oil provided the USA with: Texaco fueled Hitler’s conquest of the Spanish republic (this one is hard to hide, because the U.S. Congress slapped Texaco with a symbolic fine, well after the deed was done). That used to amuse Hitler a lot (Hitler gave elaborated reasons to his worried supporters for being in bed with American plutocrats; as the Nazi Party was officially socialist, and anti-plutocratic, that awkward situation may have led him to declare war to the USA on December 11, 1941, to ward off the German generals’ argument that he was just a little corporal in above his head).

Another example: Mussolini was hanged from an American gas station in Milan. Italian communists hanged him from his sponsors’ works.

The fueling of the fascists by American fossil fuel companies helped bring the American Century to the world in general, and Europe in particular. Without Stalin and American plutocratic oil, Hitler’s Panzers could not have moved in 1939 or 1940.

The dignified Elie Wiesel, instead of crying crocodiles tears, wondering how such a thing as Auschwitz was possible, should ask how and why the Nazi extermination machine was fuelled by American plutocrats, and how come he, himself, never talks about that.

Wiesel got the Nobel Peace Prize, just as Jimmy Carter (who launched the American attack on Afghanistan). Was it for disinformation? (And how come waging war in Afghanistan is a big plus for the Peace Prize? Is it related to the same mood which made Sweden help Hitler before and during WWII, and never having a serious look at that, ever since? I know the prize is ostensibly given by Norwegians.)

Wikipedia is big on the notion of “weasel words“, and rightly so. Deeper than that is what I would call weasel logic. And ever deeper, weasel worlds. To talk about Hitler without ever wondering who his sponsors were, and what they were after, is to live in a weasel world.

I like Elie Wiesel personally. Yet, just as I like Krugman, Obama, and countless others, such as the infamous Jean-Paul Sartre, he likes power even more than truth. OK, It is unfair to put Sartre, who really espoused the most abject terrorism, with the others… As long as individuals prefer power to truth, the spontaneous generation of infamy is insured.

Total oil sales, per day are about 100 million barrels (in truth the cap is lower, see graph above), at, say $100, so ten billion dollars a day, 3.6 trillion a year. The USA uses about 25% of that. Some have incorporated the price of the part of the gigantic American war machine and (what are truly) bribes to feudal warlords insuring Western access to the oil fields, and found a much higher cost up to $11 a gallon.

Ultimately, and pretty soon, in 2016, specialists expect oil prices to explode up, from the exhaustion of the existing oil fields. Then what?

Moreover, in 2016, the dependence upon OPEC, or, more exactly Arab regimes, is going to become much greater than now. What’s the plan of the USA? Extend ever more the security state, and go occupy the Middle East with a one million men army? To occupy, or not to occupy, that is the question.

Is it time for a better plan? And yes, any better plan will require consumers to pay higher energy prices. As consumers apparently want the army to procure the oil, they ought to pay for it.

***

Patrice Ayme

***

Note 1: Flying cost at least ten times more in CO2 creation than taking a train. And jet fuel is not taxed, at least until the carbon plan of the European Union starts charging next year, in 2013. In spite of the screaming from the USA and its proxies: it’s funny how attached to subsidies American society can be.

Note 2: Refusing to pay for necessary military expenses through taxation and mobilization, was a big factor in the downfall of the Roman Principate.

The Principate then tried to accomplish defense on the cheap, by using more and more mercenaries. Many of these mercenaries or their children and descendants were poorly integrated in Roman republican culture (say emperors Diocletian or Constantine, let alone Stilicho the Vandal, a century later), so they established theDominate, itself a negation of the Roman republic. Amusingly the Western Franks, those salt water (“Salian“) Franks remembered the Roman republic better than all these imports from the savage East… who could not remember it, they, and their ancestors, having never known it.

Guess what? The USA’s army presently employs 300,000 “private contractors” (aka, mercenaries). Curiously, in that case, it’s not so much to save money, than to extract more money from the system (but that’s another story). Still, it will have the same effect.

oooOOOooo