Back to the future – a new way of seeing forward

The concluding part of a three-part paper previously published by Professor Sherry Jarrell, Part One is here and Part Two is here.

What kinds of business establishments will thrive in the U.S. city of the future? To answer this question, we examined the count of the number of establishments per business category listed on yellowpagecity.com, adjusted proportionately to represent a population of 500,000, and found the following results.

Death services. Although the strain on the healthcare system has received much attention in relation to ageing in the United States, the next logical step—death—is rarely mentioned, although it certainly represents many business and professional opportunities. Our data suggest that the number of funeral facilities and cremations per 500,000 residents might double or even triple by 2025. The same applies to the number of cemeteries and companies listing monuments.

Healthcare. Along with roughly 30% more doctors, our data suggest that a range of medical services and products will be in greater demand by 2025. Nearly all of them relate to age. Consistent with the expectation that mental and self-care disabilities increase with age, listings also jump considerably for alcohol information and treatment, and counseling services. This trend doesn’t occur, however, for mental health services.

Real estate and living arrangements. Real estate listings significantly increase across the six MSAs, along with a substantial growth in listed land surveyors. The number of listings for nursing and convalescent homes moves from an average of 30 for the current MSAs to 50 for the 2020 and 2025 cities. There’s an even larger average rise in the number of retirement communities and homes.

Perhaps the most surprising pattern, at least initially, is the dramatic increase in the number of listings for mobile home dealers and mobile home parks and communities. Insurance studies have shown, however, that the percent of manufactured (mobile) home owners who are age 65 and older has risen from 26% in 1990 to 30% in 2002. Similar percentages are cited for owners who are retired. In addition, over the same period, the amount of owners age 80 and older has changed from 3% to 7%. Therefore, the future might be replete with mobile homes. The data might reflect the strategy of retirees selling larger homes to extract the equity, which is used to help fund retirement and buy a less-expensive manufactured home.

Activities. The data show a marked increase in the number of associations, clubs, churches, and fraternal organizations, which supports the description of mature adults as “joiners.” Bingo games are more popular in the 2020 and 2025 cities. Perhaps most noticeably, more golf is played in the 2020 and 2025 MSAs, requiring many more golf courses and golf-related products and services—not just in Florida, but also in Youngstown, Utica, and Scranton. Residents in the 2020 and 2025 cities also spend more time at the library, at recreation centers and parks, and reading newspapers.

Finance. Services that will be in higher demand as retirees seek assistance in managing their retirement assets include credit and debt counseling services, insurance, loans, mutual funds, and stock and bond brokers.

Products. The number of listings for new and used automobile dealers increases between the 2005 and 2025 cities, as do listings for new and used furniture dealers, health and diet foods, hardware, lawn and garden equipment and supplies, service stations, TV and radio equipment sales and service, and vitamins. But the data also reveal many other rising trends that are likely age-related, such as for antique dealers, arts and crafts, ceramic equipment and supplies, embroidery, gift shops, giftwares, jewelers, and security-related products. The substantial increase in florists is probably related to the number of hospitals, funeral facilities, and crematories in the cities.

Services. The Yellow Pages listings indicate many more business, employment, and investment opportunities in the future. Several categories relate to home improvement, such as contractors for remodeling, landscaping, and swimming pools. Home maintenance also is in greater demand in cities with older populations. Similarly, listings related to servicing and repairing automobiles, furniture, and jewelry rise across the three pairs of cities—along with beauty salons and massage. Pets apparently deserve no less, as pet washing and grooming services are in greater demand in cities with older populations.

Research Implications

This innovative methodology for studying various aspects of the future reveals that many of the detailed trends across the three pairs of cities have significant implications with respect to new product development and marketing. For example, marketers need to begin partnering with development and land use officials to anticipate future growth in demand for golfing facilities, churches, parks, libraries, cemeteries, and mobile home parks. And medical services providers must be prepared to meet the demands for home health services and many other healthcare preferences of older adults in an increasingly competitive environment.

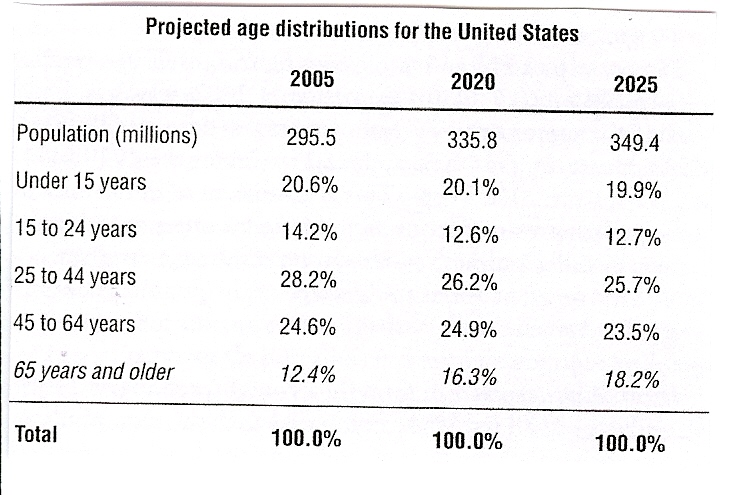

Although it’s true that many factors other than age will shape future spending patterns, such as changing tastes among mature buyers, new technology, and various economic factors, many of these trends are almost entirely age-related. Therefore, it’s unlikely the future will look that different from Lakeland today, where the share of the population age 65 and older is identical to that projected for the nation in 2025.

The United States will not be a nation of Floridas in 2025; it will be a nation of Lakelands.

By Sherry Jarrell

information” as any time a person trades while aware of material nonpublic information (US Securities and Exchange Commissions

information” as any time a person trades while aware of material nonpublic information (US Securities and Exchange Commissions