The universe and normal matter.

Frequently I look up at the night sky and ponder about so many things that I cannot understand. I wish I did but it is far too late now. But that doesn’t stop me from reading about the science and more. Here is a perfect example of that and I am delighted to be able to share it with you.

ooOOoo

Most normal matter in the universe isn’t found in planets, stars or galaxies – an astronomer explains where it’s distributed

Chris Impey, University of Arizona

If you look across space with a telescope, you’ll see countless galaxies, most of which host large central black holes, billions of stars and their attendant planets. The universe teems with huge, spectacular objects, and it might seem like these massive objects should hold most of the universe’s matter.

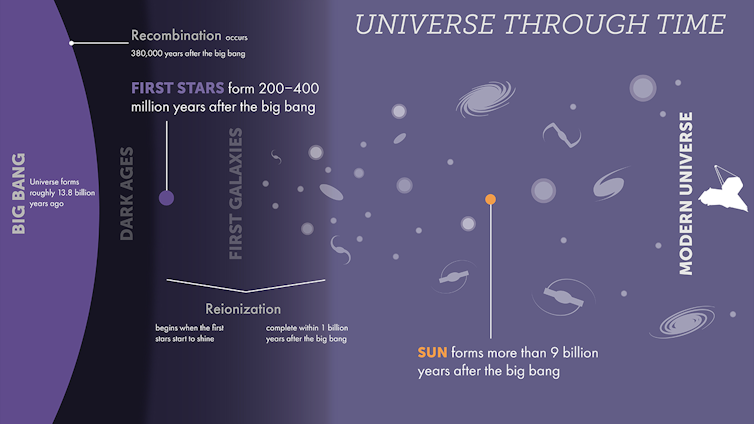

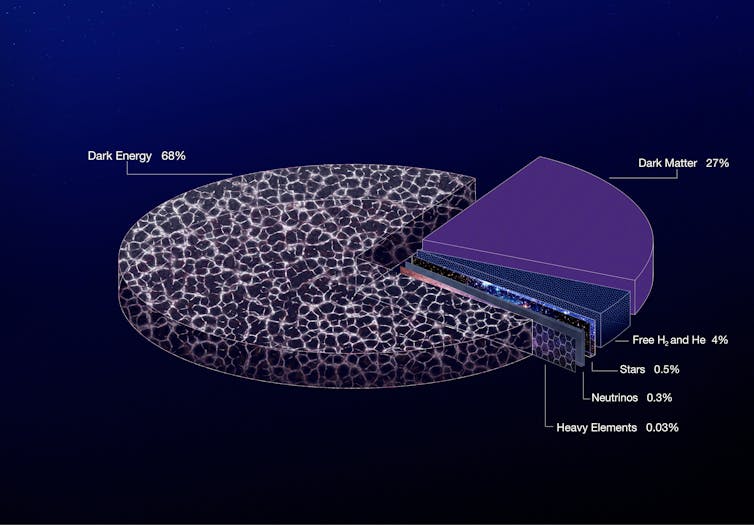

But the Big Bang theory predicts that about 5% of the universe’s contents should be atoms made of protons, neutrons and electrons. Most of those atoms cannot be found in stars and galaxies – a discrepancy that has puzzled astronomers.

If not in visible stars and galaxies, the most likely hiding place for the matter is in the dark space between galaxies. While space is often referred to as a vacuum, it isn’t completely empty. Individual particles and atoms are dispersed throughout the space between stars and galaxies, forming a dark, filamentary network called the “cosmic web.”

Throughout my career as an astronomer, I’ve studied this cosmic web, and I know how difficult it is to account for the matter spread throughout space.

In a study published in June 2025, a team of scientists used a unique radio technique to complete the census of normal matter in the universe.

The census of normal matter

The most obvious place to look for normal matter is in the form of stars. Gravity gathers stars together into galaxies, and astronomers can count galaxies throughout the observable universe.

The census comes to several hundred billion galaxies, each made of several hundred billion stars. The numbers are uncertain because many stars lurk outside of galaxies. That’s an estimated 1023 stars in the universe, or hundreds of times more than the number of sand grains on all of Earth’s beaches. There are an estimated 1082 atoms in the universe.

However, this prodigious number falls far short of accounting for all the matter predicted by the Big Bang. Careful accounting indicates that stars contain only 0.5% of the matter in the universe. Ten times more atoms are presumably floating freely in space. Just 0.03% of the matter is elements other than hydrogen and helium, including carbon and all the building blocks of life.

Looking between galaxies

The intergalactic medium – the space between galaxies – is near-total vacuum, with a density of one atom per cubic meter, or one atom every 35 cubic feet. That’s less than a billionth of a billionth of the density of air on Earth. Even at this very low density, this diffuse medium adds up to a lot of matter, given the enormous, 92-billion-light-year diameter of the universe.

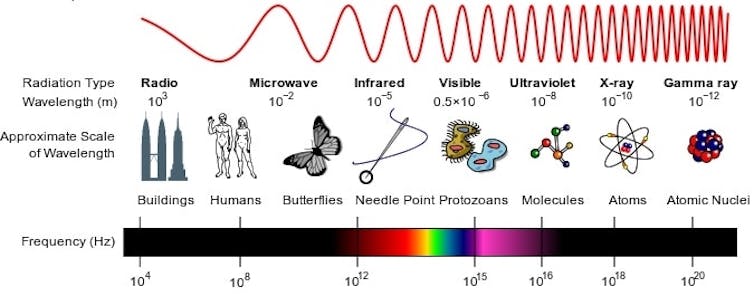

The intergalactic medium is very hot, with a temperature of millions of degrees. That makes it difficult to observe except with X-ray telescopes, since very hot gas radiates out through the universe at very short X-ray wavelengths. X-ray telescopes have limited sensitivity because they are smaller than most optical telescopes.

Deploying a new tool

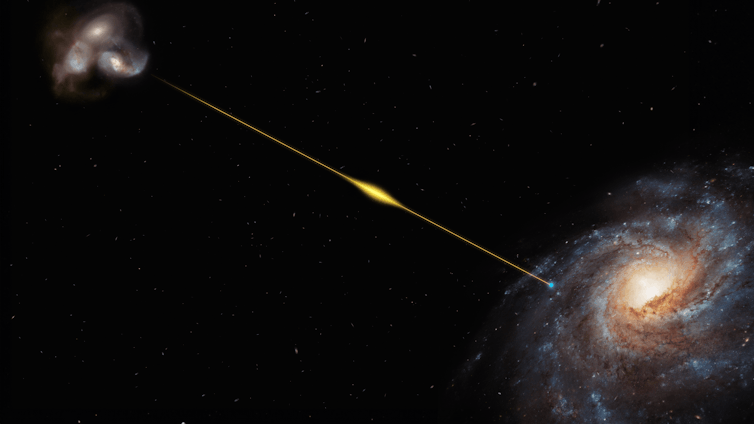

Astronomers recently used a new tool to solve this missing matter problem. Fast radio bursts are intense blasts of radio waves that can put out as much energy in a millisecond as the Sun puts out in three days. First discovered in 2007, scientists found that the bursts are caused by compact stellar remnants in distant galaxies. Their energy peters out as the bursts travel through space, and by the time that energy reaches the Earth, it is a thousand times weaker than a mobile phone signal would be if emitted on the Moon, then detected on Earth.

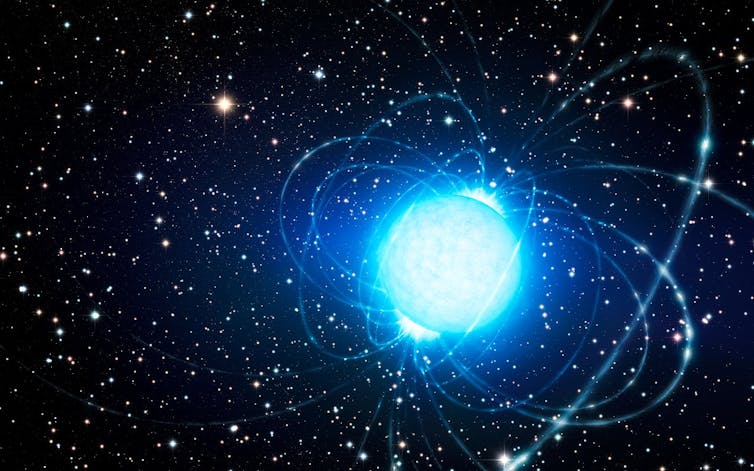

Research from early 2025 suggests the source of the bursts is the highly magnetic region around an ultra-compact neutron star. Neutron stars are incredibly dense remnants of massive stars that have collapsed under their own gravity after a supernova explosion. The particular type of neutron star that emits radio bursts is called a magnetar, with a magnetic field a thousand trillion times stronger than the Earth’s.

Even though astronomers don’t fully understand fast radio bursts, they can use them to probe the spaces between galaxies. As the bursts travel through space, interactions with electrons in the hot intergalactic gas preferentially slow down longer wavelengths. The radio signal is spread out, analogous to the way a prism turns sunlight into a rainbow. Astronomers use the amount of spreading to calculate how much gas the burst has passed through on its way to Earth.

Puzzle solved

In the new study, published in June 2025, a team of astronomers from Caltech and the Harvard Center for Astrophysics studied 69 fast radio bursts using an array of 110 radio telescopes in California. The team found that 76% of the universe’s normal matter lies in the space between galaxies, with another 15% in galaxy halos – the area surrounding the visible stars in a galaxy – and the remaining 9% in stars and cold gas within galaxies.

The complete accounting of normal matter in the universe provides a strong affirmation of the Big Bang theory. The theory predicts the abundance of normal matter formed in the first few minutes of the universe, so by recovering the predicted 5%, the theory passes a critical test.

Several thousand fast radio bursts have already been observed, and an upcoming array of radio telescopes will likely increase the discovery rate to 10,000 per year. Such a large sample will let fast radio bursts become powerful tools for cosmology. Cosmology is the study of the size, shape and evolution of the universe. Radio bursts could go beyond counting atoms to mapping the three-dimensional structure of the cosmic web.

Pie chart of the universe

Scientists may now have the complete picture of where normal matter is distributed, but most of the universe is still made up of stuff they don’t fully understand.

The most abundant ingredients in the universe are dark matter and dark energy, both of which are poorly understood. Dark energy is causing the accelerating expansion of the universe, and dark matter is the invisible glue that holds galaxies and the universe together.

Dark matter is probably a previously unstudied type of fundamental particle that is not part of the standard model of particle physics. Physicists haven’t been able to detect this novel particle yet, but we know it exists because, according to general relativity, mass bends light, and far more gravitational lensing is seen than can be explained by visible matter. With gravitational lensing, a cluster of galaxies bends and magnifies light in a way that’s analogous to an optical lens. Dark matter outweighs conventional matter by more than a factor of five.

One mystery may be solved, but a larger mystery remains. While dark matter is still enigmatic, we now know a lot about the normal atoms making up us as humans, and the world around us.

Chris Impey, University Distinguished Professor of Astronomy, University of Arizona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

The details are incredible. Take for example that three-quarters of the matter out there is found outside the galaxies. Or that there are more stars in the universe than all of the sand grains on Planet Earth.

Just amazing!