Back to dogs!

Photo by Harshit Suryawanshi on Unsplash

Photo by Peter Muniz on Unsplash

Photo by Aldo Houtkamp on Unsplash

Again, a photo by Aldo Houtkamp on Unsplash

Again, a very beautiful selection by yours truly!

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Back to dogs!

Photo by Harshit Suryawanshi on Unsplash

Photo by Peter Muniz on Unsplash

Photo by Aldo Houtkamp on Unsplash

Again, a photo by Aldo Houtkamp on Unsplash

Again, a very beautiful selection by yours truly!

Here is one explanation.

There is no question the world’s weather systems are changing. However, for folk who are not trained in this science it is all a bit mysterious. So thank goodness that The Conversation have not only got a scientist who does know what he is talking about but also they are very happy for it to be republished.

ooOOoo

Zhe Li, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

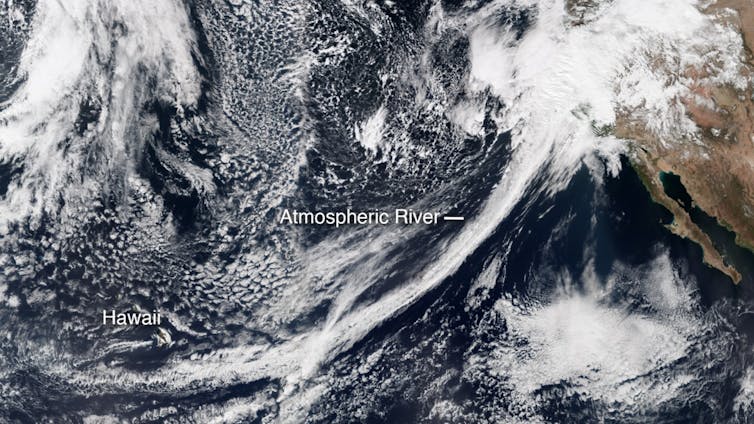

Atmospheric rivers – those long, narrow bands of water vapor in the sky that bring heavy rain and storms to the U.S. West Coast and many other regions – are shifting toward higher latitudes, and that’s changing weather patterns around the world.

The shift is worsening droughts in some regions, intensifying flooding in others, and putting water resources that many communities rely on at risk. When atmospheric rivers reach far northward into the Arctic, they can also melt sea ice, affecting the global climate.

In a new study published in Science Advances, University of California, Santa Barbara, climate scientist Qinghua Ding and I show that atmospheric rivers have shifted about 6 to 10 degrees toward the two poles over the past four decades.

Atmospheric rivers aren’t just a U.S West Coast thing. They form in many parts of the world and provide over half of the mean annual runoff in these regions, including the U.S. Southeast coasts and West Coast, Southeast Asia, New Zealand, northern Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom and south-central Chile.

California relies on atmospheric rivers for up to 50% of its yearly rainfall. A series of winter atmospheric rivers there can bring enough rain and snow to end a drought, as parts of the region saw in 2023.

While atmospheric rivers share a similar origin – moisture supply from the tropics – atmospheric instability of the jet stream allows them to curve poleward in different ways. No two atmospheric rivers are exactly alike.

What particularly interests climate scientists, including us, is the collective behavior of atmospheric rivers. Atmospheric rivers are commonly seen in the extratropics, a region between the latitudes of 30 and 50 degrees in both hemispheres that includes most of the continental U.S., southern Australia and Chile.

Our study shows that atmospheric rivers have been shifting poleward over the past four decades. In both hemispheres, activity has increased along 50 degrees north and 50 degrees south, while it has decreased along 30 degrees north and 30 degrees south since 1979. In North America, that means more atmospheric rivers drenching British Columbia and Alaska.

One main reason for this shift is changes in sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific. Since 2000, waters in the eastern tropical Pacific have had a cooling tendency, which affects atmospheric circulation worldwide. This cooling, often associated with La Niña conditions, pushes atmospheric rivers toward the poles.

The poleward movement of atmospheric rivers can be explained as a chain of interconnected processes.

During La Niña conditions, when sea surface temperatures cool in the eastern tropical Pacific, the Walker circulation – giant loops of air that affect precipitation as they rise and fall over different parts of the tropics – strengthens over the western Pacific. This stronger circulation causes the tropical rainfall belt to expand. The expanded tropical rainfall, combined with changes in atmospheric eddy patterns, results in high-pressure anomalies and wind patterns that steer atmospheric rivers farther poleward.

Conversely, during El Niño conditions, with warmer sea surface temperatures, the mechanism operates in the opposite direction, shifting atmospheric rivers so they don’t travel as far from the equator.

The shifts raise important questions about how climate models predict future changes in atmospheric rivers. Current models might underestimate natural variability, such as changes in the tropical Pacific, which can significantly affect atmospheric rivers. Understanding this connection can help forecasters make better predictions about future rainfall patterns and water availability.

A shift in atmospheric rivers can have big effects on local climates.

In the subtropics, where atmospheric rivers are becoming less common, the result could be longer droughts and less water. Many areas, such as California and southern Brazil, depend on atmospheric rivers for rainfall to fill reservoirs and support farming. Without this moisture, these areas could face more water shortages, putting stress on communities, farms and ecosystems.

In higher latitudes, atmospheric rivers moving poleward could lead to more extreme rainfall, flooding and landslides in places such as the U.S. Pacific Northwest, Europe, and even in polar regions.

In the Arctic, more atmospheric rivers could speed up sea ice melting, adding to global warming and affecting animals that rely on the ice. An earlier study I was involved in found that the trend in summertime atmospheric river activity may contribute 36% of the increasing trend in summer moisture over the entire Arctic since 1979.

So far, the shifts we have seen still mainly reflect changes due to natural processes, but human-induced global warming also plays a role. Global warming is expected to increase the overall frequency and intensity of atmospheric rivers because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture.

How that might change as the planet continues to warm is less clear. Predicting future changes remains uncertain due largely to the difficulty in predicting the natural swings between El Niño and La Niña, which play an important role in atmospheric river shifts.

As the world gets warmer, atmospheric rivers – and the critical rains they bring – will keep changing course. We need to understand and adapt to these changes so communities can keep thriving in a changing climate.

Zhe Li, Postdoctoral Researcher in Earth System Science, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

Those last two paragraphs of the above article show the difficulty in coming up with clear predictions of the future. As was said: ‘How that might change as the planet continues to warm is less clear. Predicting future changes remains uncertain due largely to the difficulty in predicting the natural swings between El Niño and La Niña, which play an important role in atmospheric river shifts.‘

My son, Alex, took the following photographs of the Aurora..

oooo

oooo

oooo

They are fabulous. Especially so because as it happened we had mainly cloud cover here in Southern Oregon.

To close, here is an extract from yesterday’s BBC website:

On Thursday night, the stunning colours of the Northern Lights were visible once again even to the naked eye across much of the US.

Experts say the Northern Lights, or Aurora Borealis, are more visible right now due to the sun being at what astronomers call the “maximum” of its 11-year solar cycle.

What this means is that roughly every 11 years, at the peak of this cycle, the sun’s magnetic poles flip, and the sun transitions from sluggish to active and stormy. On Earth, that’d be like if the North and South Poles swapped places every decade.

“At its quietest, the sun is at solar minimum; during solar maximum, the sun blazes with bright flares and solar eruptions,” according to Nasa, the US space agency.

The current 11-year cycle, the 25th since records began in 1755, started in 2019 and is expected to peak next year.

This attracted me very much, and I wanted to share it with you.

The opening paragraph of this article caught my eye so I read it fully. As it was published in The Conversation then that meant I could republish it.

ooOOoo

James L. Fitzsimmons, Middlebury

The ancient Maya believed that everything in the universe, from the natural world to everyday experiences, was part of a single, powerful spiritual force. They were not polytheists who worshipped distinct gods but pantheists who believed that various gods were just manifestations of that force.

Some of the best evidence for this comes from the behavior of two of the most powerful beings of the Maya world: The first is a creator god whose name is still spoken by millions of people every fall – Huracán, or “Hurricane.” The second is a god of lightning, K’awiil, from the early first millennium C.E.

As a scholar of the Indigenous religions of the Americas, I recognize that these beings, though separated by over 1,000 years, are related and can teach us something about our relationship to the natural world.

Huracán was once a god of the K’iche’, one of the Maya peoples who today live in the southern highlands of Guatemala. He was one of the main characters of the Popol Vuh, a religious text from the 16th century. His name probably originated in the Caribbean, where other cultures used it to describe the destructive power of storms.

The K’iche’ associated Huracán, which means “one leg” in the K’iche’ language, with weather. He was also their primary god of creation and was responsible for all life on earth, including humans.

Because of this, he was sometimes known as U K’ux K’aj, or “Heart of Sky.” In the K’iche’ language, k’ux was not only the heart but also the spark of life, the source of all thought and imagination.

Yet, Huracán was not perfect. He made mistakes and occasionally destroyed his creations. He was also a jealous god who damaged humans so they would not be his equal. In one such episode, he is believed to have clouded their vision, thus preventing them from being able to see the universe as he saw it.

Huracán was one being who existed as three distinct persons: Thunderbolt Huracán, Youngest Thunderbolt and Sudden Thunderbolt. Each of them embodied different types of lightning, ranging from enormous bolts to small or sudden flashes of light.

Despite the fact that he was a god of lightning, there were no strict boundaries between his powers and the powers of other gods. Any of them might wield lightning, or create humanity, or destroy the Earth.

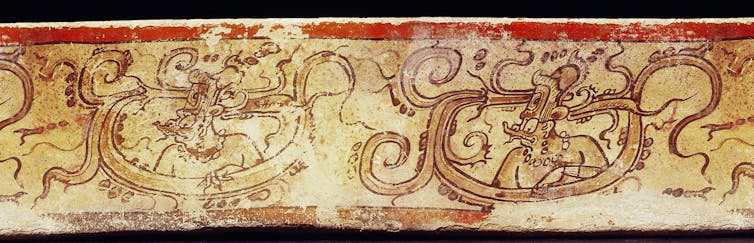

The Popol Vuh implies that gods could mix and match their powers at will, but other religious texts are more explicit. One thousand years before the Popol Vuh was written, there was a different version of Huracán called K’awiil. During the first millennium, people from southern Mexico to western Honduras venerated him as a god of agriculture, lightning and royalty.

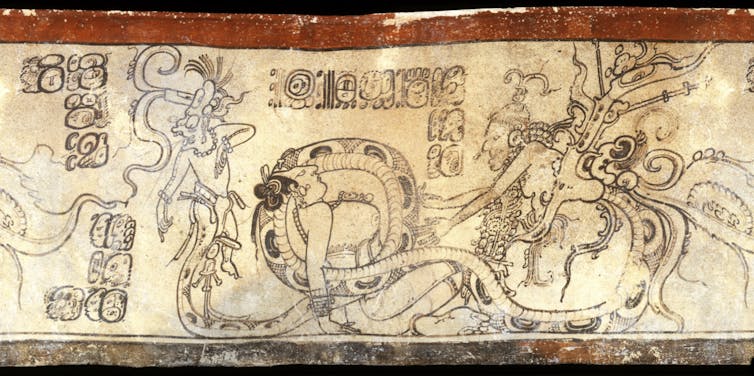

Illustrations of K’awiil can be found everywhere on Maya pottery and sculpture. He is almost human in many depictions: He has two arms, two legs and a head. But his forehead is the spark of life – and so it usually has something that produces sparks sticking out of it, such as a flint ax or a flaming torch. And one of his legs does not end in a foot. In its place is a snake with an open mouth, from which another being often emerges.

Indeed, rulers, and even gods, once performed ceremonies to K’awiil in order to try and summon other supernatural beings. As personified lightning, he was believed to create portals to other worlds, through which ancestors and gods might travel.

For the ancient Maya, lightning was raw power. It was basic to all creation and destruction. Because of this, the ancient Maya carved and painted many images of K’awiil. Scribes wrote about him as a kind of energy – as a god with “many faces,” or even as part of a triad similar to Huracán.

He was everywhere in ancient Maya art. But he was also never the focus. As raw power, he was used by others to achieve their ends.

Rain gods, for example, wielded him like an ax, creating sparks in seeds for agriculture. Conjurers summoned him, but mostly because they believed he could help them communicate with other creatures from other worlds. Rulers even carried scepters fashioned in his image during dances and processions.

Moreover, Maya artists always had K’awiil doing something or being used to make something happen. They believed that power was something you did, not something you had. Like a bolt of lightning, power was always shifting, always in motion.

Because of this, the ancient Maya thought that reality was not static but ever-changing. There were no strict boundaries between space and time, the forces of nature or the animate and inanimate worlds.

Everything was malleable and interdependent. Theoretically, anything could become anything else – and everything was potentially a living being. Rulers could ritually turn themselves into gods. Sculptures could be hacked to death. Even natural features such as mountains were believed to be alive.

These ideas – common in pantheist societies – persist today in some communities in the Americas.

They were once mainstream, however, and were a part of K’iche’ religion 1,000 years later, in the time of Huracán. One of the lessons of the Popol Vuh, told during the episode where Huracán clouds human vision, is that the human perception of reality is an illusion.

The illusion is not that different things exist. Rather it is that they exist independent from one another. Huracán, in this sense, damaged himself by damaging his creations.

Hurricane season every year should remind us that human beings are not independent from nature but part of it. And like Hurácan, when we damage nature, we damage ourselves.

James L. Fitzsimmons, Professor of Anthropology, Middlebury

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

It is such a powerful message, that when we damage nature, we damage ourselves.

But I am unaware, no we are both unaware of a solution, and there doesn’t appear to be a government desire to make this the number one topic.

Please, if there is anyone who reads this post and has a more positive message then we would be very keen to hear from you.

Back to dogs! (And apologies if there are some that I have shown before!)

oooo

Both the above are Photos by Chewy on Unsplash

And so is this one of the starry night.

And yet another photo from Chewy!

Photo by Anna Dudkova on Unsplash

Aren’t they fabulous!

This poster will be displayed frequently until October 19th.

Author’s Innovative Marketing (AIM) is pleased to present a unique opportunity to dip into the minds of eight local authors, on Saturday, October 19th, 2024. Why Write is a free event taking place in the lobby and conference room at Club Northwest, 2160 NW Vine St., in Grants Pass from 1:00 to 5:00 pm. Two panels of four authors each are scheduled to speak about why they write at 1:30 and at 3:00 pm. Hear about their backgrounds, what inspires their writing, how writing benefits them, and be able to ask questions. Talk with the authors and purchase signed copies of their books before and after the panel sessions. Food and beverages will be available for purchase. For more information, please visit Authors Innovative Marketing website.

If you are at all within range of Grants Pass, we would love to see you at the event.

August has produced a find video and it is presented today.

August Hunicke has completed the editing of the video he shot while taking down the very tall trees alongside our house on the 24th and 25th of last September.

It is shared with all of you today.

When a Smooth Job Meets Bad Company

The team involved in the project were shown in this previous post.

A fascinating article makes a fundamental point.

My mother and father were atheists so when I was born in 1944 it was obvious that I would be brought up as an atheist. Same for my sister, Elizabeth, born in 1948. It was amazing that when I met Jean in Mexico in 2007 that she, too, was an atheist. That was on top of the fact that we were both born in North London some 26 miles apart. Talk about fate!

So naturally my attention was drawn to a recent article in Free Enquiry magazine, Thinking Made Me an Atheist.

That article opens as follows:

I was abused as a child. The abuse to which I was subjected is called “child indoctrination,” a type of brainwashing considered noble and necessary and, therefore, the most natural thing in the world.

My mother took me to the Seventh-day Adventist Church, an American denomination known for keeping the Sabbath and emphasizing the advent, or return, of Jesus. Adventists boast that they are the only ones to interpret the Bible the way its author wanted. Consequently, they deem themselves the most special creatures to God—so special that they’ll soon arouse the envy and wrath of all other denominations and religions, which, under the command of the beasts of Revelation (the American government and the Catholic Church), will persecute them. Adventists believe that the Earth was created in six days, that it is 6,000 years old, and that dinosaurs are extinct because they were too big to be saved on Noah’s ark.

It closes thus:

I don’t want to believe; I want to know. Atheism is a natural result of intellectual honesty.

The author of the article, Paulo Bittencourt is described as:

Paulo Bittencourt was born in Castro, Brazil, spent his childhood in Rio de Janeiro, and studied theology in São Paulo. Close to becoming a pastor, he went on an adventure to Europe and ended up settling in Austria, where he trained as an opera singer. Bittencourt is the author of the books Liberated from Religion: The Inestimable Pleasure of Being a Freethinker and Wasting Time on God: Why I Am an Atheist.

So once again, do read this article.

We sincerely believe there is no god!