A very revealing list.

I am in touch with a fellow blogger. Her name is Bela Johnson and her blog is Belas Bright Ideas.

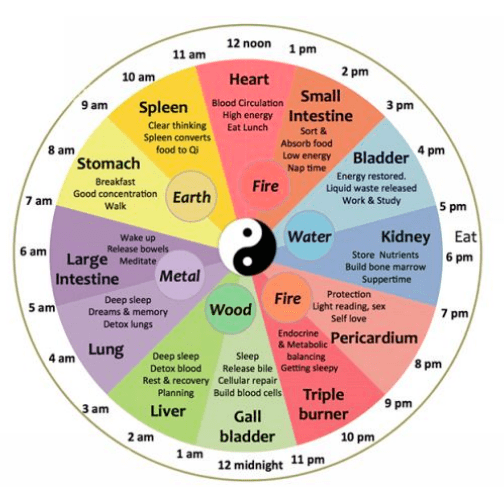

Recently, Bela sent me the following document about the body and I am reproducing it here for you.

ooOOoo

5-7 a.m. — Large Intestine — Drinking water triggers bowel evacuation making room for the new day’s nutritional intake. Removes toxins from the night’s cleansing.

7-9 a.m. — Stomach — Stomach energies are the highest so eat the most important meal of the day here to optimize digestion/assimilation.

9-11 a.m. — Pancreas — The stomach passes its contents on. Enzymes from the pancreas continue the digestive process. Carbohydrate energy made available.

11 a.m.-1 p.m. — Heart — Food materials enter the blood stream. The heart pumps nutrients throughout the system and takes its lipid requirements.

1-3 p.m. — Small Intestine — Foods requiring longer digestion times (proteins) complete their digestion/assimilation.

3-5 p.m. — Bladder — Metabolic wastes from morning’s nutrition intake clear, making room for the kidney’s filtration to come.

5-7 p.m. — Kidney — Filters blood (decides what to keep, what to throw away), maintains proper chemical balance of blood based on nutritional intake of day. Blood to deliver useable nutrients to all tissues.

7-9 p.m. — Circulation — Nutrients are carried to groups of cells (capillaries) and to each individual cell (lymphatics.)

9-11 p.m. — Triple Heater — The endocrine system adjusts the homeostasis of the body based on electrolyte and enzyme replenishment.

11 p.m.- 1 a.m. — Gall Bladder — Initial cleansing of all tissues, processes cholesterol, enhances brain function.

1-3 a.m. — Liver — Cleansing of blood. Processing of wastes.

3-5 a.m. — Lung — Respiration. Oxygenation. Expulsion of waste gasses.

Chong Mai Vessel – gives birth to REN and DU.

Kidney essence – blueprint – you agree who you are going to be: race, parents, family relationships, physical description.

Resources – REN: bones, vessels, organs, orifices.

Put in proper order (DU) – construction of blueprint.

ooOOoo

The above list came on the back of an email that Bela sent to me, and again I publish that email.

Paul I agree with all of this IN THEORY. But digestion systems are really individual. What one person can eat, another one just cannot digest. I have spent my entire life discovering what it is I ‘could’ digest! When I got into TCM Traditional Chinese medicine (because both my daughters are practitioners), it was the only system that agreed with what I’m saying to you now. We are all unique, and sometimes we present with things that are contradictory in any other system. Damp but also dry. Cold but also hot.

At any rate, the Chinese have a theory that the organs cleanse themselves while we sleep. There’s a chart (and you can look this up online), that shows what organ is cleansing at what time. So it is recommended that we eat nothing after 7 PM at the very latest. Because then the cleansing begins, and so demanding that our system digest something during the cleansing time is just really paddling upstream. So both Chris and I find that we sleep way more soundly when we don’t eat anything preferably after six, but after seven at the latest. And yes, both of us do a magnesium supplement at night. Anyhow, good to make people aware that we are what we eat in so many ways!

Finally, here is that chart and the accompanying text that largely follows what Bela published above.

Chinese Medicine’s 24 hour body clock is divided into 12 two-hour intervals of the Qi (vital force) moving through the organ system. Chinese Medicine practitioners use The Organ Body Clock to help them determine the organ responsible for diseases. For example, if you find yourself waking up between the hours of 3-5am each morning, you may have underlying grief or sadness that is bothering you or you may have a condition in the lung area. If feelings of anger or resentment arise, you may feel them strongest during the time of the Liver which is 1-3am or perhaps if you experience back pain at the end of your working day, you could have pent up emotions of fear, or perhaps even Kidney issues.

The Body-Energy Clock is built upon the concept of the cyclical ebb and flow of energy throughout the body. During a 24-hour period (see diagram that follows) Qi moves in two-hour intervals through the organ systems. During sleep, Qi draws inward to restore the body. This phase is completed between 1 and 3 a.m., when the liver cleanses the blood and performs a myriad of functions that set the stage for Qi moving outward again.

In the 12-hour period following the peak functioning of the liver—from 3 a.m. onward—energy cycles to the organs associated with daily activity, digestion and elimination: the lungs, large intestine, stomach/pancreas, heart, small intestine. By mid-afternoon, energy again moves inward to support internal organs associated with restoring and maintaining the system. The purpose is to move fluids and heat, as well as to filter and cleanse—by the pericardium, triple burner (coordinates water functions and temperature), bladder/kidneys and the liver.

5 am to 7 am is the time of the Large Intestine making it a perfect time to have a bowel movement and remove toxins from the day before. It is also the ideal time to wash your body and comb your hair. It is believed that combing your hair helps to clear out energy from the mind. At this time, emotions of defensiveness or feelings of being stuck could be evoked.

7-9am is the time of the Stomach so it is important to eat the biggest meal of the day here to optimize digestion and absorption. Warm meals that are high in nutrition are best in the morning. Emotions that are likely to be stirred at this time include disgust or despair.

9-11am is the time of the Pancreas and Spleen, where enzymes are released to help digest food and release energy for the day ahead. This is the ideal time to exercise and work. Do your most taxing tasks of the day at this time. Emotions such as low self-esteem may be felt at this time.

11am- 1pm is the time of the Heart which will work to pump nutrients around the body to help provide you with energy and nutrition. This is also a good time to eat lunch and it is recommend to have a light, cooked meal. Having a one hour nap or a cup of tea is also recommended during this time. Feelings of extreme joy or sadness can also be experienced at this time.

1-3pm is the time of the Small Intestine and is when food eaten earlier will complete its digestion and assimilation. This is also a good time to go about daily tasks or exercise. Sometimes, vulnerable thoughts or feelings of abandonment my subconsciously arise at this time.

3-5pm is the time of the Bladder when metabolic wastes move into the kidney’s filtration system. This is the perfect time to study or complete brain-challenging work. Another cup of tea is advised as is drinking a lot of water to help aid detoxification processes. Feeling irritated or timid may also occur at this time.

5-7pm is the time of the Kidneys when the blood is filtered and the kidneys work to maintain proper chemical balance. This is the perfect time to have dinner and to activate your circulation either by walking, having a massage or stretching. Subconscious thoughts of fear or terror can also be active at this time.

7-9pm is the time of Circulation when nutrients are carried to the capillaries and to each cell. This is the perfect time to read. Avoid doing mental activities at this time. A difficulty in expressing emotions may also be felt however, this is the perfect time to have sex or conceive.

9-11pm is the time of Triple Heater or endocrine system where the body’s homeostasis is adjusted and enzymes are replenished. It is recommended to sleep at this time so the body can conserve energy for the following day. Feelings of paranoia or confusion may also be felt.

11pm-1am is the time of the Gall Bladder and in order to wake feeling energized the body should be at rest. In Chinese medicine, this period of time is when yin energy fades ad yang energy begins to grow. Yang energy helps you to keep active during the day and is stored when you are asleep. Subconscious feelings of resentment may appear during this time.

1-3am is the time of the Liver and a time when the body should be alseep. During this time, toxins are released from the body and fresh new blood is made. If you find yourself waking during this time, you could have too much yang energy or problems with your liver or detoxification pathways. This is also the time of anger, frustration and rage.

3-5am the time of the Lungs and again, this is the time where the body should be asleep. If woken at this time, nerve soothing exercises are recommended such as breathing exercises. The body should be kept warm at this time too to help the lungs replenish the body with oxygen. The lungs are also associated with feelings of grief and sadness.

Understanding that every organ has a repair/maintenance schedule to keep on a daily basis offers you the opportunity to learn how to treat yourself for improved health and well-being. It also allows you to identify exactly which organ system or emotion needs strengthening/resolving. Always use your symptoms and body cues as a guide, and if you make a connection above, such as that you get sleepy between 5-7pm, don’t hesitate to research what you can do to strengthen that meridian (which would be the Kidneys). A great solution to deficient kidneys is having a sweet potato for breakfast!

Make sure to look at the emotional aspect too. If you’re sleepy during kidney time, do you have any fears holding you back from reaching your true potential? Are you afraid of rejection? Failure? Addressing this emotion will strengthen the organ and improve your physical health forever.

With the transferable knowledge of TCM you can use the clock for any time of day.