More gorgeous pictures, and a saying, from Jess.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

This last saying has an ‘ouch’ to it.

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Author: Paul Handover

We take our decision from watching the animal kingdom.

A recent post in The Conversation provides the article for today’s blog post.

ooOOoo

At Cambridge University Library, along with all the books, maps and manuscripts, there’s a child’s drawing that curators have titled “The Battle of the Fruit and Vegetable Soldiers.”

The drawing depicts a turbaned cavalry soldier facing off against an English dragoon. It’s a bit trippy: The British soldier sits astride a carrot, and the turbaned soldier rides a grape. Both carrot and grape are fitted with horses’ heads and stick appendages.

It’s thought to be the work of Francis Darwin, the seventh child of British naturalist Charles Darwin and his wife, Emma, and appears to have been made in 1857, when Frank would have been 10 or 11. And it’s drawn on the back of a page of a draft of “On the Origin of Species,” Darwin’s masterwork and the foundational text of evolutionary biology. The few sheets of the draft that survive are pages Darwin gave to his children to use for drawing paper.

Darwin’s biographers have long recognized that play was important in his personal and familial life. The Georgian manor in which he and Emma raised their 10 children was furnished with a rope swing hung over the first-floor landing and a portable wooden slide that could be laid over the main stairway. The gardens and surrounding countryside served as an open-air laboratory and playground.

Play also has a role in Darwin’s theory of natural selection. As I explain in my new book, “Kingdom of Play: What Ball-bouncing Octopuses, Belly-flopping Monkeys, and Mud-sliding Elephants Reveal about Life Itself,” there are many similarities – so many that if you could distill the processes of natural selection into a single behavior, that behavior would be play.

Natural selection is the process by which organisms that are best adapted to their environments are more likely to survive, and so able to pass on the characteristics that helped them thrive to their offspring. It is undirected: In Darwin’s words, it “includes no necessary and universal law of advancement or development.”

Through natural selection, the rock pocket mouse has evolved a coat color that hides it from predators in the desert Southwest.

In contrast to foraging and hunting – behaviors with clearly defined goals – play is likewise undirected. When a pony frolics in a field, a dog wrestles with a stick or chimpanzees chase each other, they act with no goal in mind.

Natural selection is utterly provisional: The evolution of any organism responds to whatever conditions are present at a given place and time. Likewise, animals at play are acting provisionally. They constantly adjust their movements in response to changes in circumstances. Playing squirrels, faced with obstacles such as falling branches or other squirrels, nimbly alter their tactics and routes.

Natural selection is open-ended. The forms of life are not fixed, but continually evolving. Play, too, is open-ended. Animals begin a play session with no plan of when to end it. Two dogs play-fighting, for instance, cease playing only when one is injured, exhausted or simply loses interest.

Natural selection also is wasteful, as Darwin acknowledged. “Many more individuals of each species are born than can possibly survive,” he wrote. But in the long term, he allowed, such profligacy could produce adaptations that enable an evolutionary line to become “more fit.”

Keepers noticed that Shanthi, a 36-year-old elephant at the Smithsonian national zoo, liked to make noise with objects, so they gave her horns, harmonicas and other noisemakers.

Play is likewise profligate. It requires an animal to expend time and energy that perhaps would be better devoted to behaviors such as foraging and hunting that could aid survival.

And that profligacy is also advantageous. Animals forage and hunt in specific ways that don’t typically change. But an animal at play is far more likely to innovate – and some of its innovations may in time be adapted into new ways to forage and hunt.

As Darwin first framed it, the “struggle for existence” was by and large a competition. But in the 1860s, Russian naturalist Pyotr Kropotkin’s observations of birds and fallow deer led him to conclude that many species were “the most numerous and the most prosperous” because natural selection also selects for cooperation.

Scientists confirmed Kroptokin’s hypothesis in the 20th century, discovering all manner of cooperation, not only between members of the same species but between members of different species. For example, clown fish are immune to anemone stings; they nestle in anemone tentacles for protection and, in return, keep the anemones free of parasites, provide nutrients and drive away predators.

Play likewise utilizes both competition and cooperation. Two dogs play-fighting are certainly competing, yet to sustain their play, they must cooperate. They often reverse roles: A dog with the advantage of position might suddenly surrender that advantage and roll over on its back. If one bites harder than intended, it is likely to retreat and perform a play bow – saying, in effect, “My bad. I hope we can keep playing.”

River otters at the Oregon Zoo repeatedly separate and reunite while playing in a tub of ice.

Natural selection and play also may both employ deception. From butterflies colored to resemble toxic species to wild cats that squeal like distressed baby monkeys, many organisms use mimicry to deceive their prey, predators and rivals. Play – specifically, play-fighting – similarly offers animals opportunities to learn about and practice deception.

Darwin wrote that natural selection creates “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful.” Play also creates beauty in countless ways, from the aerial acrobatics of birds of prey to the arcing, twisting leaps of dolphins.

In 1973, Ukrainian-American geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky published an essay with the take-no-prisoners title “Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution.” Many biologists would agree. Perhaps the most satisfying definition of life attends not to what it is but to what it does – which is to say, life is what evolves by natural selection.

And since natural selection shares so many features with play, we may with some justification maintain that life, in a most fundamental sense, is playful.

David Toomey, Professor of English, UMass Amherst

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

Prof. Toomey’s analysis is spot-on.

All of life involves some form of play.

It is a pure emotion yet it can be complex!

So many know this already but that won’t stop me repeating it. As a result of me seeing a psychologist in early 2007 I became aware of me having a fear of rejection. Now a conscious fear but it had been an unconscious fear since my father died in 1956.

So me meeting Jean in December, 2007 was the first time that I found true love despite when we were married Jean becoming my fourth wife.

Thus the following post that is copied from The Conversation is brilliant and is shared with you all.

ooOOoo

Edith Gwendolyn Nally, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Love is confusing. People in the U.S. Google the word “love” about 1.2 million times a month. Roughly a quarter of those searches ask “what is love” or request a “definition of love.”

What is all this confusion about?

Neuroscience tells us that love is caused by certain chemicals in the brain. For example, when you meet someone special, the hormones dopamine and norepinephrine can trigger a reward response that makes you want to see this person again. Like tasting chocolate, you want more.

Your feelings are the result of these chemical reactions. Around a crush or best friend, you probably feel something like excitement, attraction, joy and affection. You light up when they walk into the room. Over time, you might feel comfort and trust. Love between a parent and child feels different, often some combination of affection and care.

But are these feelings, caused by chemical reactions in your brain, all that love is? If so, then love seems to be something that largely happens to you. You’d have as much control over falling in love as you’d have over accidentally falling in a hole – not much.

As a philosopher who studies love, I’m interested in the different ways people have understood love throughout history. Many thinkers have believed that love is more than a feeling.

The ancient Greek philosopher Plato thought that love might cause feelings like attraction and pleasure, which are out of your control. But these feelings are less important than the loving relationships you choose to form as a result: lifelong bonds between people who help one another change and grow into their best selves.

Similarly, Plato’s student Aristotle claimed that, while relationships built on feelings like pleasure are common, they’re less good for humankind than relationships built on goodwill and shared virtues. This is because Aristotle thought relationships built on feelings last only as long as the feelings last.

Imagine you start a relationship with someone you have little in common with other than you both enjoy playing video games. Should either of you no longer enjoy gaming, nothing would hold the relationship together. Because the relationship is built on pleasure, it will fade once the pleasure is gone.

Compare this with a relationship where you want to be together not because of a shared pleasure but because you admire one another for who you are. You want what is best for one another. This kind of friendship built on shared virtue and goodwill will be much longer lasting. These kinds of friends will support each other as they change and grow.

Plato and Aristotle both thought that love is more than a feeling. It’s a bond between people who admire one another and therefore choose to support one another over time.

Maybe, then, love isn’t totally out of your control.

Contemporary philosopher J. David Velleman also thinks that love can be disentangled from “the likings and longings” that come with it – those butterflies in your stomach. This is because love isn’t just a feeling. It’s a special kind of paying attention, which celebrates a person’s individuality.

Velleman says Dr. Seuss did a good job describing what it means to celebrate a person’s individuality when he wrote: “Come on! Open your mouth and sound off at the sky! Shout loud at the top of your voice, ‘I AM I! ME! I am I!’” When you love someone, you celebrate them because you value the “I AM I” that they are.

You can also get better at love. Social psychologist Erich Fromm thinks that loving is a skill that takes practice: what he calls “standing in love.” When you stand in love, you act in certain ways toward a person.

Just like learning to play an instrument, you can also get better at loving with patience, concentration and discipline. This is because standing in love is made up of other skills such as listening carefully and being present. If you get better at these skills, you can get better at loving.

If this is the case, then love and friendship are distinct from the feelings that accompany them. Love and friendship are bonds formed by skills you choose to practice and improve.

Does this mean you could stand in love with someone you hate, or force yourself to stand in love with someone you have no feelings for whatsoever?

Probably not. Philosopher Virginia Held explains the difference between doing an activity and participating in a practice as simply doing some labor versus doing some labor while also enacting values and standards.

Compare a math teacher who mechanically solves a problem at the board versus a teacher who provides students a detailed explanation of the solution. The mechanical teacher is doing the activity – presenting the solution – whereas the engaged teacher is participating in the practice of teaching. The engaged teacher is enacting good teaching values and standards, such as creating a fun learning environment.

Standing in love is a practice in the same sense. It’s not just a bunch of activities you perform. To really stand in love is to do these activities while enacting loving values and standards, such as empathy, respect, vulnerability, honesty and, if Velleman is right, celebrating a person for who they truly are.

Is it best to understand love as a feeling or a choice?

Think about what happens when you break up with someone or lose a friend. If you understand love purely in terms of the feelings it stirs up, the love is over once these feelings disappear, change or get put on hold by something like a move or a new school.

On the other hand, if love is a bond you choose and practice, it will take much more than the disappearance of feelings or life changes to end it. You or your friend might not hang out for a few days, or you might move to a new city, but the love can persist.

If this understanding is right, then love is something you have more control over than it may seem. Loving is a practice. And, like any practice, it involves activities you can choose to do – or not do – such as hanging out, listening and being present. In addition, practicing love will involve enacting the right values, such as respect and empathy.

While the feelings that accompany love might be out of your control, how you love someone is very much in your control.

Edith Gwendolyn Nally, Associate Professor of Philosophy, University of Missouri-Kansas City

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

An article from Live Science tells all.

Before I share the article with you, I felt I should mention that I haven’t found a link to share the Live Science item and it may need to be moved. We will see what happens.

ooOOoo

Dogs can smell their humans’ stress, and it makes them sad.

By Sara Novak, published July 27, 2024.

Dogs can smell when people are stressed, and it seems to make them feel downhearted.

Humans and dogs have been close companions for perhaps 30,000 years, according to anthropological and DNA evidence. So it would make sense that dogs would be uniquely qualified to interpret human emotion. They have evolved to read verbal and visual cues from their owners, and previous research has shown that with their acute sense of smell, they can even detect the odor of stress in human sweat. Now researchers have found that not only can dogs smell stress—in this case represented by higher levels of the hormone cortisol—they also react to it emotionally.

For the new study, published Monday in Scientific Reports, scientists at the University of Bristol in England recruited 18 dogs of varying breeds, along with their owners. Eleven volunteers who were unfamiliar to the dogs were put through a stress test involving public speaking and arithmetic while samples of their underarm sweat were gathered on pieces of cloth. Next, the human participants underwent a relaxation exercise that included watching a nature video on a beanbag chair under dim lighting, after which new sweat samples were taken. Sweat samples from three of these volunteers were used in the study.

Participating canines were put into three groups and smelled sweat samples from one of the three volunteers. Prior to doing so, the dogs were trained to know that a food bowl at one location contained a treat and that a bowl at another location did not. During testing, bowls that did not contain a treat were sometimes placed in one of three “ambiguous” locations. In one testing session, when the dogs smelled the sample from a stressed volunteer, compared with the scent of a cloth without a sample, they were less likely to approach the bowl in one of the ambiguous locations, suggesting that they thought this bowl did not contain a treat. Previous research has shown that an expectation of a negative outcome reflects a down mood in dogs.

The results imply that when dogs are around stressed individuals, they’re more pessimistic about uncertain situations, whereas proximity to people with the relaxed odor does not have this effect, says Zoe Parr-Cortes, lead study author and a Ph.D. student at Bristol Veterinary School at the University of Bristol. “For thousands of years, dogs have learned to live with us, and a lot of their evolution has been alongside us. Both humans and dogs are social animals, and there’s an emotional contagion between us,” she says. “Being able to sense stress from another member of the pack was likely beneficial because it alerted them of a threat that another member of the group had already detected.”

The fact that the odor came from an individual who was unfamiliar to the dogs speaks to the importance of smell for the animals and to the way it affects emotions in such practical situations, says Katherine A. Houpt, a professor emeritus of behavioral medicine at Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. Houpt, who was not involved in the new study, suggests that the smell of stress may have reduced the dogs’ hunger because it’s known to impact appetite. “It might not be that it’s changing their decision-making but more that it’s changing their motivation for food,” she says. “It makes sense because when you’re super stressed, you’re not quite as interested in that candy bar.”

This research, Houpt adds, shows that dogs have empathy based on smell in addition to visual and verbal cues. And when you’re stressed, that could translate into behaviors that your dog doesn’t normally display, she says. What’s more, it leaves us to wonder how stress impacts the animals under the more intense weight of an anxious owner. “If the dogs are responding to more mild stress like this, I’d be interested to see how they responded to something more serious like an impending tornado, losing your job or failing a test,” Houpt says. “One would expect the dog to be even more attuned to an actual threat.”

Sara Novak, Science Writer

Sara Novak is a science writer based on Sullivan’s Island, S.C. Her work has appeared in Discover, Sierra Magazine, Popular Science, New Scientist, and more. Follow Novak on X (formerly Twitter) @sarafnovak

ooOOoo

Dogs are such perfect animals and Sara brings this out so well. As was pointed out in the article dogs have learned to live with us humans over thousands of years.

Well done, Sara!

Beyond our imagination.

Until quite recently I had imagined that a tree was just a tree. Then Jean and I got to watch a YouTube video on trees and it blew our minds. Here is what we watched:

That led us on to watching Judi Dench’s video of trees:

Which is a longish introduction to a piece on The Conversation about trees.

ooOOoo

Delphine Farmer, Colorado State University and Mj Riches, Colorado State University

When wildfire smoke is in the air, doctors urge people to stay indoors to avoid breathing in harmful particles and gases. But what happens to trees and other plants that can’t escape from the smoke?

They respond a bit like us, it turns out: Some trees essentially shut their windows and doors and hold their breath.

As atmospheric and chemical scientists, we study the air quality and ecological effects of wildfire smoke and other pollutants. In a study that started quite by accident when smoke overwhelmed our research site in Colorado, we were able to watch in real time how the leaves of living pine trees responded.

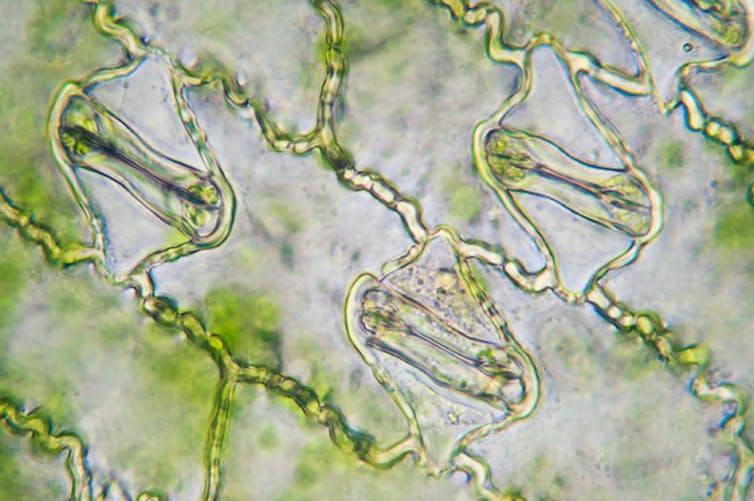

Plants have pores on the surface of their leaves called stomata. These pores are much like our mouths, except that while we inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, plants inhale carbon dioxide and exhale oxygen.

Both humans and plants inhale other chemicals in the air around them and exhale chemicals produced inside them – coffee breath for some people, pine scents for some trees.

Unlike humans, however, leaves breathe in and out at the same time, constantly taking in and releasing atmospheric gases.

In the early 1900s, scientists studying trees in heavily polluted areas discovered that those chronically exposed to pollution from coal-burning had black granules clogging the leaf pores through which plants breathe. They suspected that the substance in these granules was partly created by the trees, but due to the lack of available instruments at the time, the chemistry of those granules was never explored, nor were the effects on the plants’ photosynthesis.

Most modern research into wildfire smoke’s effects has focused on crops, and the results have been conflicting.

For example, a study of multiple crop and wetland sites in California showed that smoke scatters light in a way that made plants more efficient at photosynthesis and growth. However, a lab study in which plants were exposed to artificial smoke found that plant productivity dropped during and after smoke exposure – though those plants did recover after a few hours.

There are other clues that wildfire smoke can impact plants in negative ways. You may have even tasted one: When grapes are exposed to smoke, their wine can be tainted.

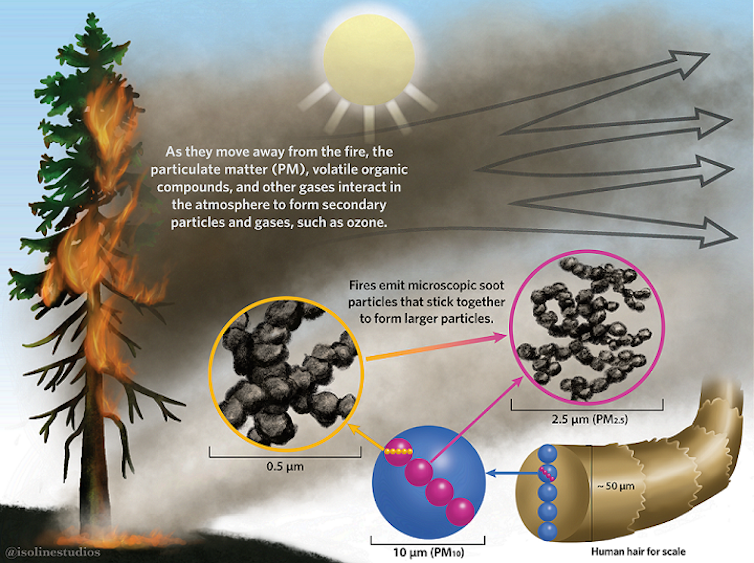

When wildfire smoke travels long distances, the smoke cooks in sunlight and chemically changes.

Mixing volatile organic compounds, nitrogen oxides and sunlight will make ground-level ozone, which can cause breathing problems in humans. It can also damage plants by degrading the leaf surface, oxidizing plant tissue and slowing photosynthesis.

While scientists usually think about urban regions as being large sources of ozone that effect crops downwind, wildfire smoke is an emerging concern. Other compounds, including nitrogen oxides, can also harm plants and reduce photosynthesis.

Taken together, studies suggest that wildfire smoke interacts with plants, but in poorly understood ways. This lack of research is driven by the fact that studying smoke effects on the leaves of living plants in the wild is hard: Wildfires are hard to predict, and it can be unsafe to be in smoky conditions.

We didn’t set out to study plant responses to wildfire smoke. Instead, we were trying to understand how plants emit volatile organic compounds – the chemicals that make forests smell like a forest, but also impact air quality and can even change clouds.

Fall 2020 was a bad season for wildfires in the western U.S., and thick smoke came through a field site where we were working in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado.

On the first morning of heavy smoke, we did our usual test to measure leaf-level photosynthesis of Ponderosa pines. We were surprised to discover that the tree’s pores were completely closed and photosynthesis was nearly zero.

We also measured the leaves’ emissions of their usual volatile organic compounds and found very low readings. This meant that the leaves weren’t “breathing” – they weren’t inhaling the carbon dioxide they need to grow and weren’t exhaling the chemicals they usually release.

With these unexpected results, we decided to try to force photosynthesis and see if we could “defibrillate” the leaf into its normal rhythm. By changing the leaf’s temperature and humidity, we cleared the leaf’s “airways” and saw a sudden improvement in photosynthesis and a burst of volatile organic compounds.

What our months of data told us is that some plants respond to heavy bouts of wildfire smoke by shutting down their exchange with outside air. They are effectively holding their breath, but not before they have been exposed to the smoke.

We hypothesize a few processes that could have caused leaves to close their pores: Smoke particles could coat the leaves, creating a layer that prevents the pores from opening. Smoke could also enter the leaves and clog their pores, keeping them sticky. Or the leaves could physically respond to the first signs of smoke and close their pores before they get the worst of it.

It’s likely a combination of these and other responses.

The jury is still out on exactly how long the effects of wildfire smoke last and how repeated smoke events will affect plants – including trees and crops – over the long term.

With wildfires increasing in severity and frequency due to climate change, forest management policies and human behavior, it’s important to gain a better understanding of the impact.

Delphine Farmer, Professor of Chemistry, Colorado State University and Mj Riches, Postdoctoral Researcher in Environmental and Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

The biggest tree in the world is reputed to be the General Sherman tree in California. Here is the introduction from WikiPedia:

General Sherman is a giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) tree located at an elevation of 2,109 m (6,919 ft) above sea level in the Giant Forest of Sequoia National Park in Tulare County, in the U.S. state of California. By volume, it is the largest known living single-stem tree on Earth.

Amazing!

Now for a change!

Jess has sent me a great collection of dog pictures that she has found on Instagram and elsewhere and for a few weeks I am going to be sharing them with you.

oooo

oooo

This is a very touching photo. Dogs grieve about loss just as we do. Jess

oooo

oooo

oooo

More from Jess next Sunday.

That’s the fire in California that is growing so quickly!

There are so many stories around about these dogs being rescued. I have chosen the YouTube video which is the CBS News, Chicago, presentation.

A homeowner was forced to leave their truck behind with the adult rottweiler and her puppies. The owner told rescuers where they were, but the intense fire blocked access to the truck. Several days later, rescuers spotted the dogs from a helicopter and landed to get them.

More information on this terrible condition.

As you know, Jean suffers from PD and was diagnosed in 2015.

Very recently there was this article on PD and I reproduce parts of it (I have not applied for permission to republish) but I have provided the link to a pdf.

ooOOoo

by WEHI

Mitochondria (blue) being targeted by mitophagy (green and red). Credit: WEHI

Parkinson’s disease is the world’s fastest growing neurological condition. Currently there are no drugs or therapies that slow or stop the progression of the disease.

In Australia, someone is diagnosed with Parkinson’s approximately every 30 minutes. Current estimates show there are more than 219,000 people living with Parkinson’s in Australia, a number forecast to double in the next 15 years.

WEHI’s Parkinson’s Disease Research Center has some of the world’s leading researchers tackling the problem using a multi-disciplinary collaborative approach.

Mitochondria are the energy generating machines in our cells and are kept healthy by mitophagy, which is the molecular process of removing or recycling damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria.

PINK1 and Parkin are two key genes involved in mitophagy, and mutations in these genes are linked to early-onset Parkinson’s disease.

Until the discovery of two proteins, NAP1 and SINTBAD, exactly how PINK1/Parkin mitophagy activation was regulated was unknown.

ooOOoo

We wish the scientists all the best as they delve into PD.

That link to the PDF file is https://www.nature.com/articles/s41594-024-01338-y