And it’s all about getting the vote out!

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

All taken courtesy of the BBC.

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Year: 2018

And it’s all about getting the vote out!

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

All taken courtesy of the BBC.

Is how you think the same as how she thinks?

The challenge of how you think, and whether or not it is similar to how others think has long intrigued us.

Tam Hunt has written an article that now ponders on whether how we think, how we are conscious of the world around us, depends on how that ‘thing’ vibrates.

Over to Tam.

ooOOoo

By Affiliate Guest in Psychology, University of California, Santa Barbara

Why is my awareness here, while yours is over there? Why is the universe split in two for each of us, into a subject and an infinity of objects? How is each of us our own center of experience, receiving information about the rest of the world out there? Why are some things conscious and others apparently not? Is a rat conscious? A gnat? A bacterium?

These questions are all aspects of the ancient “mind-body problem,” which asks, essentially: What is the relationship between mind and matter? It’s resisted a generally satisfying conclusion for thousands of years.

The mind-body problem enjoyed a major rebranding over the last two decades. Now it’s generally known as the “hard problem” of consciousness, after philosopher David Chalmers coined this term in a now classic paper and further explored it in his 1996 book, “The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory.”

Chalmers thought the mind-body problem should be called “hard” in comparison to what, with tongue in cheek, he called the “easy” problems of neuroscience: How do neurons and the brain work at the physical level? Of course they’re not actually easy at all. But his point was that they’re relatively easy compared to the truly difficult problem of explaining how consciousness relates to matter.

Over the last decade, my colleague, University of California, Santa Barbara psychology professor Jonathan Schooler and I have developed what we call a “resonance theory of consciousness.” We suggest that resonance – another word for synchronized vibrations – is at the heart of not only human consciousness but also animal consciousness and of physical reality more generally. It sounds like something the hippies might have dreamed up – it’s all vibrations, man! – but stick with me.

All about the vibrations

All things in our universe are constantly in motion, vibrating. Even objects that appear to be stationary are in fact vibrating, oscillating, resonating, at various frequencies. Resonance is a type of motion, characterized by oscillation between two states. And ultimately all matter is just vibrations of various underlying fields. As such, at every scale, all of nature vibrates.

Something interesting happens when different vibrating things come together: They will often start, after a little while, to vibrate together at the same frequency. They “sync up,” sometimes in ways that can seem mysterious. This is described as the phenomenon of spontaneous self-organization.

Mathematician Steven Strogatz provides various examples from physics, biology, chemistry and neuroscience to illustrate “sync” – his term for resonance – in his 2003 book “Sync: How Order Emerges from Chaos in the Universe, Nature, and Daily Life,” including:

Examining resonance leads to potentially deep insights about the nature of consciousness and about the universe more generally.

Sync inside your skull

Neuroscientists have identified sync in their research, too. Large-scale neuron firing occurs in human brains at measurable frequencies, with mammalian consciousness thought to be commonly associated with various kinds of neuronal sync.

For example, German neurophysiologist Pascal Fries has explored the ways in which various electrical patterns sync in the brain to produce different types of human consciousness.

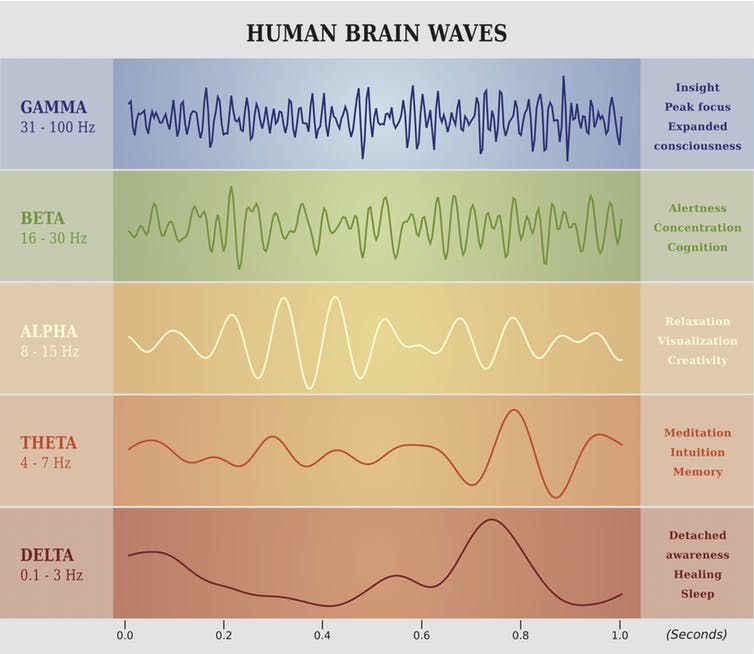

Fries focuses on gamma, beta and theta waves. These labels refer to the speed of electrical oscillations in the brain, measured by electrodes placed on the outside of the skull. Groups of neurons produce these oscillations as they use electrochemical impulses to communicate with each other. It’s the speed and voltage of these signals that, when averaged, produce EEG waves that can be measured at signature cycles per second.

Gamma waves are associated with large-scale coordinated activities like perception, meditation or focused consciousness; beta with maximum brain activity or arousal; and theta with relaxation or daydreaming. These three wave types work together to produce, or at least facilitate, various types of human consciousness, according to Fries. But the exact relationship between electrical brain waves and consciousness is still very much up for debate.

Fries calls his concept “communication through coherence.” For him, it’s all about neuronal synchronization. Synchronization, in terms of shared electrical oscillation rates, allows for smooth communication between neurons and groups of neurons. Without this kind of synchronized coherence, inputs arrive at random phases of the neuron excitability cycle and are ineffective, or at least much less effective, in communication.

A resonance theory of consciousness

Our resonance theory builds upon the work of Fries and many others, with a broader approach that can help to explain not only human and mammalian consciousness, but also consciousness more broadly.

Based on the observed behavior of the entities that surround us, from electrons to atoms to molecules, to bacteria to mice, bats, rats, and on, we suggest that all things may be viewed as at least a little conscious. This sounds strange at first blush, but “panpsychism” – the view that all matter has some associated consciousness – is an increasingly accepted position with respect to the nature of consciousness.

The panpsychist argues that consciousness did not emerge at some point during evolution. Rather, it’s always associated with matter and vice versa – they’re two sides of the same coin. But the large majority of the mind associated with the various types of matter in our universe is extremely rudimentary. An electron or an atom, for example, enjoys just a tiny amount of consciousness. But as matter becomes more interconnected and rich, so does the mind, and vice versa, according to this way of thinking.

Biological organisms can quickly exchange information through various biophysical pathways, both electrical and electrochemical. Non-biological structures can only exchange information internally using heat/thermal pathways – much slower and far less rich in information in comparison. Living things leverage their speedier information flows into larger-scale consciousness than what would occur in similar-size things like boulders or piles of sand, for example. There’s much greater internal connection and thus far more “going on” in biological structures than in a boulder or a pile of sand.

Under our approach, boulders and piles of sand are “mere aggregates,” just collections of highly rudimentary conscious entities at the atomic or molecular level only. That’s in contrast to what happens in biological life forms where the combinations of these micro-conscious entities together create a higher level macro-conscious entity. For us, this combination process is the hallmark of biological life.

The central thesis of our approach is this: the particular linkages that allow for large-scale consciousness – like those humans and other mammals enjoy – result from a shared resonance among many smaller constituents. The speed of the resonant waves that are present is the limiting factor that determines the size of each conscious entity in each moment.

As a particular shared resonance expands to more and more constituents, the new conscious entity that results from this resonance and combination grows larger and more complex. So the shared resonance in a human brain that achieves gamma synchrony, for example, includes a far larger number of neurons and neuronal connections than is the case for beta or theta rhythms alone.

What about larger inter-organism resonance like the cloud of fireflies with their little lights flashing in sync? Researchers think their bioluminescent resonance arises due to internal biological oscillators that automatically result in each firefly syncing up with its neighbors.

Is this group of fireflies enjoying a higher level of group consciousness? Probably not, since we can explain the phenomenon without recourse to any intelligence or consciousness. But in biological structures with the right kind of information pathways and processing power, these tendencies toward self-organization can and often do produce larger-scale conscious entities.

Our resonance theory of consciousness attempts to provide a unified framework that includes neuroscience, as well as more fundamental questions of neurobiology and biophysics, and also the philosophy of mind. It gets to the heart of the differences that matter when it comes to consciousness and the evolution of physical systems.

It is all about vibrations, but it’s also about the type of vibrations and, most importantly, about shared vibrations.

ooOOoo

Well, I’m not sure of the relevance but I’m bound to say that I am going to the doctor once a week for Alpha-Sim resetting. The reason I mention it is the Alpha frequency in the above brain wave chart. I sit very quietly for about 90 minutes and it does seem to provide some benefit.

Those eyes!

Of all the dogs that we can look at the Siberian Husky takes the biscuit! I’m talking about those eyes!

Up until reading this article in the Smithsonian I hadn’t really stopped to wonder how those eyes came about.

Read on …

ooOOoo

A new study suggests that the defining trait is linked to a unique genetic mutation

At-home DNA kits have become a popular way to learn more about one’s ancestry and genetic makeup—and the handy tests aren’t just for humans, either. Dog owners who want to delve into their fluffy friends’ family history and uncover the risks of possible diseases can choose from a number of services that screen doggie DNA.

As Kitson Jazynka reports for National Geographic, one of these services, Embark Veterinary, Inc., recently analyzed user data to unlock an enduring canine mystery: How did Siberian huskies get their brilliant blue eyes?

Piercing peepers are a defining trait of this beautiful doggo. According to the new study, published in PLOS Genetics, breeders report that blue eyes are a common and dominant trait among Siberian huskies, but appear to be rare and recessive in other breeds, like Pembroke Welsh corgis, old English sheepdogs and border collies. In some breeds, like Australian shepherds, blue eyes have been linked to patchy coat patterns known as “merle” and “piebald,” which are caused by certain genetic mutations. But it was not clear why other dogs—chief among them the Siberian husky—frequently wind up with blue eyes.

Hoping to crack this genetic conundrum, researchers at Embark studied the DNA of more than 6,000 pooches, whose owners had taken their dogs’ saliva samples and submitted them to the company for testing. The owners also took part in an online survey and uploaded photos of their dogs. According to the study authors, their research marked “the first consumer genomics study ever conducted in a non-human model and the largest canine genome-wide association study to date.”

The expansive analysis revealed that blue eyes in Siberian huskies appear to be associated with a duplication on what is known as canine chromosome 18, which is located near a gene called ALX4. This gene plays an important role in mammalian eye development, leading the researchers to suspect that the duplication “may alter expression of ALX4, which may lead to repression of genes involved in eye pigmentation,” Aaron Sams of Embark tells Inverse’s Sarah Sloat.

The genetic variation was also linked to blue eyes in non-merle Australian shepherds. Just one copy of the mutated sequence was enough to give dogs either two blue eyes, or one blue and one brown eye, a phenomenon known as “heterochromia.” It would seem, however, that duplication on chromosome 18 is not the only factor influencing blue eye color: Some dogs that had the mutation did not have blue eyes.

More research into this topic is needed to understand the genetic mechanisms at work when it comes to blue-eyed dogs. But the study shows how at-home DNA kits can be highly valuable to scientists, providing them with a wealth of genetic samples to study.

“With 6,000 people getting DNA samples from their dogs and mailing them to a centralized location and then filling out a website form detailing all the traits of their dog—that’s a game-changer for how genetics is being done in the 21st century,” Kristopher Irizarry, a geneticist with the College of Veterinary Medicine at Western University of Health Sciences, tells National Geographic’s Jazynka.

The benefits of having access to such huge troves of data go further than uncovering nifty insights into our canine companions. Scientists are also teaming up with at-home DNA test companies to learn more about human genetics and behavior.

ooOOoo

There’s such a wide range of information about our lovely dogs!

Oh, and I had better include the following.

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on TwitterRead more: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/how-siberian-huskies-get-their-piercing-blue-eyes-180970507/#4cO22KfQH7w6qp6B.99

Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter

See you all tomorrow!

Yet another dog food recall.

ooOOoo

November 9, 2018

Lidl USA is voluntarily recalling specific lots of Orlando brand Grain Free Chicken & Chickpea Superfood Recipe Dog Food because the products may contain elevated levels of Vitamin D.

The recalled Orlando brand products include the following lot numbers manufactured between March 3, 2018 and May 15, 2018:

Dogs consuming elevated levels of Vitamin D could exhibit symptoms such as vomiting, loss of appetite, increased thirst, increased urination, excessive drooling, and weight loss.

Customers with dogs who have consumed this product and are exhibiting these symptoms should contact their veterinarian as soon as possible.

No other products sold by Lidl are impacted by the recall.

This is a voluntary recall and is being conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Customers who have purchased this product with the affected lot codes should stop feeding it to their dogs and discard the product immediately or return it to their nearest Lidl store for a full refund.

Customers who have questions about this recall should call the Lidl US Customer Care Hotline at 844-747-5435, 8 AM to 9 PM Eastern time, 7 days a week.

U.S. citizens can report complaints about FDA-regulated pet food products by calling the consumer complaint coordinator in your area.

Or go to http://www.fda.gov/petfoodcomplaints.

Canadians can report any health or safety incidents related to the use of this product by filling out the Consumer Product Incident Report Form.

Get free dog food recall alerts sent to you by email. Subscribe to The Dog Food Advisor’s emergency recall notification system.

ooOOoo

Please share this amongst all your friends.

I can do no better than republish in full the following:

(Simply because I scarcely understand it!)

ooOOoo

Famous physicists like Richard Feynman think 137 holds the answers to the Universe.

By PAUL RATNER, 31st October, 2018.

Does the Universe around us have a fundamental structure that can be glimpsed through special numbers?

The brilliant physicist Richard Feynman (1918-1988) famously thought so, saying there is a number that all theoretical physicists of worth should “worry about”. He called it “one of the greatest damn mysteries of physics: a magic number that comes to us with no understanding by man”.

That magic number, called the fine structure constant, is a fundamental constant, with a value which nearly equals 1/137. Or 1/137.03599913, to be precise. It is denoted by the Greek letter alpha – α.

What’s special about alpha is that it’s regarded as the best example of a pure number, one that doesn’t need units. It actually combines three of nature’s fundamental constants – the speed of light, the electric charge carried by one electron, and the Planck’s constant, as explains physicist and astrobiologist Paul Davies to Cosmos magazine. Appearing at the intersection of such key areas of physics as relativity, electromagnetism and quantum mechanics is what gives 1/137 its allure.

Physicist Laurence Eaves, a professor at the University of Nottingham, thinks the number 137 would be the one you’d signal to the aliens to indicate that we have some measure of mastery over our planet and understand quantum mechanics. The aliens would know the number as well, especially if they developed advanced sciences.

The number preoccupied other great physicists as well, including the Nobel Prize winning Wolfgang Pauli (1900-1958) who was obsessed with it his whole life.

“When I die my first question to the Devil will be: What is the meaning of the fine structure constant?” Pauli joked.

Pauli also referred to the fine structure constant during his Nobel lecture on December 13th, 1946 in Stockholm, saying a theory was necessary that would determine the constant’s value and “thus explain the atomistic structure of electricity, which is such an essential quality of all atomic sources of electric fields actually occurring in nature.”

One use of this curious number is to measure the interaction of charged particles like electrons with electromagnetic fields. Alpha determines how fast an excited atom can emit a photon. It also affects the details of the light emitted by atoms. Scientists have been able to observe a pattern of shifts of light coming from atoms called “fine structure” (giving the constant its name). This “fine structure” has been seen in sunlight and the light coming from other stars.

The constant figures in other situations, making physicists wonder why. Why does nature insist on this number? It has appeared in various calculations in physics since the 1880s, spurring numerous attempts to come up with a Grand Unified Theory that would incorporate the constant since. So far no single explanation took hold. Recent research also introduced the possibility that the constant has actually increased over the last six billion years, even though slightly.

If you’d like to know the math behind fine structure constant more specifically, the way you arrive at alpha is by putting the 3 constants h,c, and e together in the equation —

As the units c, e, and h cancel each other out, the “pure” number of 137.03599913 is left behind. For historical reasons, says Professor Davies, the inverse of the equation is used 2πe2/hc = 1/137.03599913. If you’re wondering what is the precise value of that fraction – it’s 0.007297351.

ooOOoo

Now, as I said in my introduction, I don’t understand this. But it doesn’t stop me from marvelling at the figure.

An update to last Saturday’s post.

Earlier yesterday afternoon Jim Goodbrod sent me the following email. I should explain for those that are unfamiliar with Jim that he is a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM). He is also a friend and neighbour.

Hey Paul,

I read your guest blog yesterday regarding canine helminthiasis (ie. worms) and just wanted to comment that none of Ms. Turner’s so-called home remedies will do anything to rid your dog of worms.

I don’t know where these people get these strange remedies. Her chamomile tincture actually has a good quantity of ethanol in it, in the form of vodka or rum (?????) I’d never give that to my dog.

Over the years I’ve heard dozens of clients extol the virtues of these “natural” worming therapies from Tabasco sauce, chewing tobacco, oral diatomaceous earth, habanero peppers, garlic, turpentine, old motor oil etc. etc. Vinegar was in vogue for a long time as a cure-all for almost any ailment. Lately coconut oil seems to be the miracle cure.

I don’t know why they persist in giving their dogs ineffective treatments that make their dogs sick, when they could go to the Grange or Mini Pet Mart and get a benign over-the-counter veterinary medication such as pyrantel or praziquantel which is actually specifically labelled for the treatment of certain worms. Or better yet, many heartworm preventives contain an intestinal wormer, and since all dogs in this area should be on heartworm medication anyway, each month you would be preventing heartworms and treating intestinal worms at the same time.

That’s what I do for Louie. He loves those Heartgard treats!

Anyway, just a comment, for what it’s worth.Regards, Jim

I am very grateful to Jim giving me his permission to publish his advice.