Still more wonderful pictures, courtesy of Neil Kelly.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

Still more to come for next Sunday!

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Year: 2013

Still more wonderful pictures, courtesy of Neil Kelly.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

Still more to come for next Sunday!

Philosopher Daniel Dennett offers a kind of self-help book for deep thinkers.

Those of you that are regular followers of Learning from Dogs know that I tend to offer posts for the week-end that are light-hearted. Certainly that’s easier for me, if you pardon me from saying, and hopefully a change for you, dear reader.

Well today’s offering is not exactly heavy but it is, nonetheless, not a typical Saturday topic.

However, trust you find it engaging.

Of the many blogs and websites that I follow, I enjoy the regular mental stimulation that flows from the blog Big Think. Recently there was a piece from Daniel Dennett that tickled my interest and I wanted to share it here.

Wikipedia describes Daniel Dennett as follows:

Daniel Clement “Dan” Dennett III (born March 28, 1942) is an American philosopher, writer and cognitive scientist whose research centers on the philosophy of mind, philosophy of science and philosophy of biology, particularly as those fields relate to evolutionary biology and cognitive science.

This is the Big Think piece that caught my eye. Enjoy!

oooOOOooo

While Silicon Valley and Silicon Alley busy themselves making every aspect of our lives more efficient (except, perhaps, for the process of discovering these new technologies, learning them, and integrating them into our lives), Daniel Dennett sits up at Tufts University in Massachusetts, philosophizing. His latest book, Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking is an attempt to make transparent some of the tricks of the philosopher’s trade. In an accelerating age, it’s a self-help book designed to slow the reader down and improve our ability to think things through.

The kinds of things Mr. Dennett likes to think about include the nature of consciousness, evolution, and religious belief. But the mind-training his new book offers is applicable to any problem you want to consider thoroughly. In an age of quick fixes and corner-cutting, we’re in constant danger of bad decision making – of overreliance on what cognitive psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls “system 1”, and what most of us call intuition. This rapid decision making channel of the brain is helpful when we are in mortal danger, or pressed for a quick decision within our areas of expertise. But for most decisions, the slower, more deliberate channel (system 2) is much more reliable. What Dennett offers, then, in Intuition Pumps, is a workout for system 2 – a series of thought experiments you can apply to puzzles real and imagined to bulk up the slower, wiser parts of your consciousness.

Some of the tools Dennett offers in the book are more familiar than others. Reductio ad absurdum arguments, for example, in which we test the validity of a claim by taking it to its most outrageous illogical extreme (a: “all living things have a right to liberty.” b: “so let me get this straight – a blade of grass has a right to liberty? What does that even mean?”). But the true delights of the book are the far-out exercises Dennett and his colleagues have dreamed up in the course of their work, such as “Swampman Meets A Cow-Shark”, from Donald Davidson, which begins:

Suppose lightning strikes a dead tree in a swamp; I am standing nearby. My body is reduced to its elements, while entirely by coincidence (and out of different molecules) the tree is turned into my physical replica. My replica, The Swampman, moves exactly as I did; according to its nature it departs the swamp, encounters and seems to recognize my friends, and appears to return their greetings in English.

Walking us through Davidson’s considerations about whether and to what extent the Swampman is anything like Davidson, and related ones about a cow that gives birth to something that looks exactly like a shark (yet has cow DNA in all of its cells), Dennett teaches us a surprising lesson about the utility of wild philosophical speculation.

Cloaked in the breezy, familiar trappings of a self-help book, Intuition Pumps is in actuality a dark mirror of that genre – a field of rabbit holes designed to leave the reader with more questions than answers, and wiser for the long and indirect journey.

Watch for Daniel Dennett’s Tools For Better Thinking – a Big Think Mentor workshop coming soon.

oooOOOooo

Don’t know about you but Daniel Dennett’s book looks like one that deserves reading. If you feel the same way the book is called Intuition Pumps And Other Tools for Thinking and here’s the link to Amazon.

Perhaps the last frontier, the one underneath our feet?

Can’t recall where I came across this BBC program but so what! The fact is that the BBC have had a long and well-deserved reputation for making some fabulous programmes on nature and wildlife. So it was with a recent programme from the BBC Nature stable. The one that caught my eye and the motivation for today’s LfD post was called The Burrowers: Animals Underground.

Here is the trailer.

Published on Aug 9, 2013 Discover with BBC Two the secret life of Rabbits, Badgers and Water Voles.

Offering us this:

The Burrowers: Animals Underground

Chris Packham continues his underground journey investigating the world of some of the UK’s most iconic burrowing animals. Filmmakers and scientists cannot investigate animal behaviour inside wild burrows without disturbing them so The Burrowers’ team found ingenious ways to film this secret world by recreating full-scale replicas. It’s now spring in the burrows and the new babies are having to grow up fast. The seven orphan badgers are learning to communicate with each other, young rabbits must take their first steps outside, and young water voles their first swim. Chris also meets the most elusive burrower of them all – an animal which almost never comes above ground – the mole. He reveals the moles’ survival techniques, its method of burrowing and the food it eats. Finally, the team unveils a science first: the excavation of a massive abandoned wild rabbit warren… Back in winter it was filled with concrete and left to set. Now a small army of volunteers and diggers have excavated it, revealing a three-dimensional model of a complex system of tunnels and chambers.

So despite it being at the other end of the scale compared to the cosmos, we still know so little about what goes on beneath our feet.

Mind you, that doesn’t stop some of us from trying to find out!

Tom Engelhardt of TomDispatch and the clarity of looking backwards.

A few weeks ago, I said that I was trying to move away from writing about the big issues in our lives and refocus on the meanings, both literal and figurative, on what we can learn from dogs. Not been entirely successful with that ambition!

For example, yesterday’s post that included the most incredible video illustrating the size of the universe didn’t mention the ‘dog’ word at all. However, what yesterday did do is to remind us that even the grandest aspect of mankind’s behaviours, of the rise and fall of empires, is a very long way from the the grandness of the universe.

So with that preamble, let me move on to Tom’s recent essay, again published with Tom’s permission. As so often with essays that are published on TomDispatch this one sets out a reality of the America of today that is surely unsustainable. Interesting times!

oooOOOooo

Posted by Tom Engelhardt at 8:01am, September 3, 2013.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter @TomDispatch.

And Then There Was One – Delusional Thinking in the Age of the Single Superpower

By Tom Engelhardt

In an increasingly phantasmagorical world, here’s my present fantasy of choice: someone from General Keith Alexander’s outfit, the National Security Agency, tracks down H.G. Wells’s time machine in the attic of an old house in London. Britain’s subservient Government Communications Headquarters, its version of the NSA, is paid off and the contraption is flown to Fort Meade, Maryland, where it’s put back in working order. Alexander then revs it up and heads not into the future like Wells to see how our world ends, but into the past to offer a warning to Americans about what’s to come.

He arrives in Washington on October 23, 1962, in the middle of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a day after President Kennedy has addressed the American people on national television to tell them that this planet might not be theirs — or anyone else’s — for long. (“We will not prematurely or unnecessarily risk the costs of worldwide nuclear war in which even the fruits of victory would be ashes in our mouth, but neither will we shrink from the risk at any time it must be faced.”) Greeted with amazement by the Washington elite, Alexander, too, goes on television and informs the same public that, in 2013, the major enemy of the United States will no longer be the Soviet Union, but an outfit called al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), and that the headquarters of our country’s preeminent foe will be found somewhere in the rural backlands of… Yemen.

Yes, Yemen, a place most Americans, then and now, would be challenged to find on a world map. I guarantee you one thing: had such an announcement actually been made that day, most Americans would undoubtedly have dropped to their knees and thanked God for His blessings on the American nation. Though even then a nonbeliever, I would undoubtedly have been among them. After all, the 18-year-old Tom Engelhardt, on hearing Kennedy’s address, genuinely feared that he and the few pathetic dreams of a future he had been able to conjure up were toast.

Had Alexander added that, in the face of AQAP and similar minor jihadist enemies scattered in the backlands of parts of the planet, the U.S. had built up its military, intelligence, and surveillance powers beyond anything ever conceived of in the Cold War or possibly in the history of the planet, Americans of that time would undoubtedly have considered him delusional and committed him to an asylum.

Such, however, is our world more than two decades after Eastern Europe was liberated, the Berlin Wall came down, the Cold War definitively ended, and the Soviet Union disappeared.

Why Orwell Was Wrong

Now, let me mention another fantasy connected to the two-superpower Cold War era: George Orwell’s 1948 vision of the world of 1984 (or thereabouts, since the inhabitants of his novel of that title were unsure just what year they were living in). When the revelations of NSA contractor Edward Snowden began to hit the news and we suddenly found ourselves knee-deep in stories about Prism, XKeyscore, and other Big Brother-ish programs that make up the massive global surveillance network the National Security Agency has been building, I had a brilliant idea — reread 1984.

At a moment when Americans were growing uncomfortably aware of the way their government was staring at them and storing what they had previously imagined as their private data, consider my soaring sense of my own originality a delusion of my later life. It lasted only until I read an essay by NSA expert James Bamford in which he mentioned that, “[w]ithin days of Snowden’s documents appearing in the Guardian and the Washington Post…, bookstores reported a sudden spike in the sales of George Orwell’s classic dystopian novel 1984. On Amazon.com, the book made the ‘Movers & Shakers’ list and skyrocketed 6,021 percent in a single day.”

Nonetheless, amid a jostling crowd of worried Americans, I did keep reading that novel and found it at least as touching, disturbing, and riveting as I had when I first came across it sometime before Kennedy went on TV in 1962. Even today, it’s hard not to marvel at the vision of a man living at the beginning of the television age who sensed how a whole society could be viewed, tracked, controlled, and surveiled.

But for all his foresight, Orwell had no more power to peer into the future than the rest of us. So it’s no fault of his that, almost three decades after his year of choice, more than six decades after his death, the shape of our world has played havoc with his vision. Like so many others in his time and after, he couldn’t imagine the disappearance of the Soviet Union or at least of Soviet-like totalitarian states. More than anything else, he couldn’t imagine one fact of our world that, in 1948, wasn’t in the human playbook.

In 1984, Orwell imagined a future from what he knew of the Soviet and American (as well as Nazi, Japanese, and British) imperial systems. In imagining three equally powerful, equally baleful superpowers — Oceania, Eurasia, and Eastasia — balanced for an eternity in an unwinnable global struggle, he conjured up a logical extension of what had been developing on this planet for hundreds of years. His future was a version of the world humanity had lived with since the first European power mounted cannons on a wooden ship and set sail, like so many Mongols of the sea, to assault and conquer foreign realms, coastlines first.

From that moment on, the imperial powers of this planet — super, great, prospectively great, and near great — came in contending or warring pairs, if not triplets or quadruplets. Portugal, Spain, and Holland; England, France, and Imperial Russia; the United States, Germany, Japan, and Italy (as well as Great Britain and France), and after World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union. Five centuries in which one thing had never occurred, the thing that even George Orwell, with his prodigious political imagination, couldn’t conceive of, the thing that makes 1984 a dated work and his future a past that never was: a one-superpower world. To give birth to such a creature on such a planet — as indeed occurred in 1991 — was to be at the end of history, at least as it had long been known.

The Decade of the Stunned Superpower

Only in Hollywood fantasies about evil super-enemies was “world domination” by a single power imaginable. No wonder that, more than two decades into our one-superpower present, we still find it hard to take in this new reality and what it means.

At least two aspects of such a world seem, however, to be coming into focus. The evidence of the last decades suggests that the ability of even the greatest of imperial powers to shape global events may always have been somewhat exaggerated. The reason: power itself may never have been as centrally located in imperial or national entities as was once imagined. Certainly, with all rivals removed, the frustration of Washington at its inability to control events in the Greater Middle East and elsewhere could hardly be more evident. Still, Washington has proven incapable of grasping the idea that there might be forms of power, and so of resistance to American desires, not embodied in competitive states.

Evidence also seems to indicate that the leaders of a superpower, when not countered by another major power, when lacking an arms race to run or territory and influence to contest, may be particularly susceptible to the growth of delusional thinking, and in particular to fantasies of omnipotence.

Though Great Britain far outstripped any competitor or potential enemy at the height of its imperial glory, as did the United States at the height of the Cold War (the Soviet Union was always a junior superpower), there were at least rivals around to keep the leading power “honest” in its thinking. From December 1991, when the Soviet Union declared itself no more, there were none and, despite the dubious assumption by many in Washington that a rising China will someday be a major competitor, there remain none. Even if economic power has become more “multipolar,” no actual state contests the American role on the planet in a serious way.

Just as still water is a breeding ground for mosquitos, so single-superpowerdom seems to be a breeding ground for delusion. This is a phenomenon about which we have to be cautious, since we know little enough about it and are, of course, in its midst. But so far, there seem to have been three stages to the development of whatever delusional process is underway.

Stage one stretched from December 1991 through September 10, 2001. Think of it as the decade of the stunned superpower. After all, the collapse of the Soviet Union went unpredicted in Washington and when it happened, the George H. W. Bush administration seemed almost incapable of taking it in. In the years that followed, there was the equivalent of a stunned silence in the corridors of power.

After a brief flurry of debate about a post-Cold War “peace dividend,” that subject dropped into the void, while, for example, U.S. nuclear forces, lacking their major enemy of the previous several decades, remained more or less in place, strategically disoriented but ready for action. In those years, Washington launched modest and halting discussions of the dangers of “rogue states” (think “Axis of Evil” in the post-9/11 era), but the U.S. military had a hard time finding a suitable enemy other than its former ally in the Persian Gulf, Iraq’s Saddam Hussein. Its ventures into the world of war in Somalia and the former Yugoslavia were modest and not exactly greeted with rounds of patriotic fervor at home. Even the brief glow of popularity the elder Bush gained from his 1990-1991 war against Saddam evaporated so quickly that, by the time he geared up for his reelection campaign barely a year later, it was gone.

In the shadows, however, a government-to-be was forming under the guise of a think tank. It was filled with figures like future Vice President Dick Cheney, future Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, future Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, future U.N. Ambassador John Bolten, and future ambassador to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad, all of whom firmly believed that the United States, with its staggering military advantage and lack of enemies, now had an unparalleled opportunity to control and reorganize the planet. In January 2001, they came to power under the presidency of George W. Bush, anxious for the opportunity to turn the U.S. into the kind of global dominator that would put the British and even Roman empires to shame.

In the shadows, however, a government-to-be was forming under the guise of a think tank. It was filled with figures like future Vice President Dick Cheney, future Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, future Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, future U.N. Ambassador John Bolten, and future ambassador to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad, all of whom firmly believed that the United States, with its staggering military advantage and lack of enemies, now had an unparalleled opportunity to control and reorganize the planet. In January 2001, they came to power under the presidency of George W. Bush, anxious for the opportunity to turn the U.S. into the kind of global dominator that would put the British and even Roman empires to shame.

Pax Americana Dreams

Stage two in the march into single-superpower delusion began on September 11, 2001, only five hours after hijacked American Airlines Flight 77 smashed into the Pentagon. It was then that Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, already convinced that al-Qaeda was behind the attacks, nonetheless began dreaming about completing the First Gulf War by taking out Saddam Hussein. Of Iraq, he instructed an aide to “go massive… Sweep it all up. Things related and not.”

And go massive he and his colleagues did, beginning the process that led to the March 2003 invasion of Iraq, itself considered only a precursor to transforming the Greater Middle East into an American protectorate. From the fertile soil of 9/11 — itself something of a phantasmagoric event in which Osama bin Laden and his relatively feeble organization spent a piddling $400,000-$500,000 to create the look of an apocalyptic moment — sprang full-blown a sense of American global omnipotence.

It had taken a decade to mature. Now, within days of the toppling of those towers in lower Manhattan, the Bush administration was already talking about launching a “war on terror,” soon to become the “Global War on Terror” (no exaggeration intended). The CIA would label it no less grandiosly a “Worldwide Attack Matrix.” And none of them were kidding. Finding “terror” groups of various sorts in up to 80 countries, they were planning, in the phrase of the moment, to “drain the swamp” — everywhere.

In the early Bush years, dreams of domination bred like rabbits in the hothouse of single-superpower Washington. Such grandiose thinking quickly invaded administration and Pentagon planning documents as the Bush administration prepared to prevent potentially oppositional powers or blocs of powers from arising in the foreseeable future. No one, as its top officials and their neocon supporters saw it, could stand in the way of their planetary Pax Americana.

Nor, as they invaded Afghanistan, did they have any doubt that they would soon take down Iraq. It was all going to be so easy. Such an invasion, as one supporter wrote in the Washington Post, would be a “cakewalk.” By the time American troops entered Iraq, the Pentagon already had plans on the drawing board to build a series of permanent bases — they preferred to call them “enduring camps” — and garrison that assumedly grateful country at the center of the planet’s oil lands for generations to come.

Nobody in Washington was thinking about the possibility that an American invasion might create chaos in Iraq and surrounding lands, sparking a set of Sunni-Shiite religious wars across the region. They assumed that Iran and Syria would be forced to bend their national knees to American power or that we would simply impose submission on them. (As a neoconservative quip of the moment had it, “Everyone wants to go to Baghdad. Real men want to go to Tehran.”) And that, of course would only be the beginning. Soon enough, no one would challenge American power. Nowhere. Never.

Such soaring dreams of — quite literally — world domination met no significant opposition in mainstream Washington. After all, how could they fail? Who on Earth could possibly oppose them or the U.S. military? The answer seemed too obvious to need to be stated — not until, at least, their all-conquering armies bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan and the greatest power on the planet faced the possibility of defeat at the hands of… well, whom?

The Dark Matter of Global Power

Until things went sour in Iraq, theirs would be a vision of the Goliath tale in which David (or various ragtag Sunni, Shiite, and Pashtun versions of the same) didn’t even have a walk-on role. All other Goliaths were gone and the thought that a set of minor Davids might pose problems for the planet’s giant was beyond imagining, despite what the previous century’s history of decolonization and resistance might have taught them. Above all, the idea that, at this juncture in history, power might not be located overwhelmingly and decisively in the most obvious place — in, that is, “the finest fighting force that the world has ever known,” as American presidents of this era came to call it — seemed illogical in the extreme.

Who in the Washington of that moment could have imagined that other kinds of power might, like so much dark matter in the universe, be mysteriously distributed elsewhere on the planet? Such was their sense of American omnipotence, such was the level of delusional thinking inside the Washington bubble.

Despite two treasury-draining disasters in Afghanistan and Iraq that should have been sobering when it came to the hidden sources of global power, especially the power to resist American wishes, such thinking showed only minimal signs of diminishing even as the Bush administration pulled back from the Iraq War, and a few years later, after a set of misbegotten “surges,” the Obama administration decided to do the same in Afghanistan.

Instead, Washington entered stage three of delusional life in a single-superpower world. Its main symptom: the belief in the possibility of controlling the planet not just through staggering military might but also through informational and surveillance omniscience and omnipotence. In these years, the urge to declare a global war on communications, create a force capable of launching wars in cyberspace, and storm the e-beaches of the Internet and the global information system proved overwhelming. The idea was to make it impossible for anyone to write, say, or do anything to which Washington might not be privy.

For most Americans, the Edward Snowden revelations would pull back the curtain on the way the National Security Agency, in particular, has been building a global network for surveillance of a kind never before imagined, not even by the totalitarian regimes of the previous century. From domestic phone calls to international emails, from the bugging of U.N. headquarters and the European Union to 80 embassies around the world, from enemies to frenemies to allies, the system by 2013 was already remarkably all-encompassing. It had, in fact, the same aura of grandiosity about it, of overblown self-regard, that went with the launching of the Global War on Terror — the feeling that if Washington did it or built it, they would come.

I’m 69 years old and, in technological terms, I’ve barely emerged from the twentieth century. In a conversation with NSA Director Keith Alexander, known somewhat derisively in the trade as “Alexander the Geek,” I have no doubt that I’d be lost. In truth, I can barely grasp the difference between what the NSA’s Prism and XKeyscore programs do. So call me technologically senseless, but I can still recognize a deeper senselessness when I see it. And I can see that Washington is building something conceptually quite monstrous that will change our country for the worse, and the world as well, and is — perhaps worst of all — essentially nonsensical.

So let me offer those in Washington a guarantee: I have no idea what the equivalents of the Afghan and Iraq wars will be in the surveillance world, but continue to build such a global system, ignoring the anger of allies and enemies alike, and “they” indeed will come. Such delusional grandiosity, such dreams of omnipotence and omniscience cannot help but generate resistance and blowback in a perfectly real world that, whatever Washington thinks, maintains a grasp on perfectly real power, even without another imperial state on any horizon.

2014

Today, almost 12 years after 9/11, the U.S. position in the world seems even more singular. Militarily speaking, the Global War on Terror continues, however namelessly, in the Obama era in places as distant as Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia. The U.S. military remains heavily deployed in the Greater Middle East, though it has pulled out of Iraq and is drawing down in Afghanistan. In recent years, U.S. power has, in an exceedingly public manner, been “pivoting” to Asia, where the building of new bases, as well as the deployment of new troops and weaponry, to “contain” that imagined future superpower China has been proceeding apace.

At the same time, the U.S. military has been ever-so-quietly pivoting to Africa where, as TomDispatch’s Nick Turse reports, its presence is spreading continent-wide. American military bases still dot the planet in remarkable profusion, numbering perhaps 1,000 at a moment when no other nation on Earth has more than a handful outside its territory.

The reach of Washington’s surveillance and intelligence networks is unique in the history of the planet. The ability of its drone air fleet to assassinate enemies almost anywhere is unparalleled. Europe and Japan remain so deeply integrated into the American global system as to be essentially a part of its power-projection capabilities.

This should be the dream formula for a world dominator and yet no one can look at Planet Earth today and not see that the single superpower, while capable of creating instability and chaos, is limited indeed in its ability to control developments. Its president can’t even form a “coalition of the willing” to launch a limited series of missile attacks on the military facilities of the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad. From Latin America to the Greater Middle East, the American system is visibly weakening, while at home, inequality and poverty are on the rise, infrastructure crumbles, and national politics is in a state of permanent “gridlock.”

Such a world should be fantastical enough for the wildest sort of dystopian fiction, for perhaps a novel titled 2014. What, after all, are we to make of a planet with a single superpower that lacks genuine enemies of any significance and that, to all appearances, has nonetheless been fighting a permanent global war with… well, itself — and appears to be losing?

Tom Engelhardt, co-founder of the American Empire Project and author of The United States of Fear as well as a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture (recently published in a Kindle edition), runs the Nation Institute’s TomDispatch.com. His latest book, co-authored with Nick Turse, is Terminator Planet: The First History of Drone Warfare, 2001-2050.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook or Tumblr. Check out the newest Dispatch book, Nick Turse’s The Changing Face of Empire: Special Ops, Drones, Proxy Fighters, Secret Bases, and Cyberwarfare.

Copyright 2013 Tom Engelhardt

oooOOOooo

But as my preamble reminded us, if Tom’s essay gets your emotions running, then turn back to yesterday’s post and put it all back into place!

More or less makes daily hassles irrelevant!

Now don’t misunderstand me. There are huge numbers of people on this planet who have challenges and issues that I can’t even imagine handling. But whatever we are dealing with, it is at a personal ‘size’ proportional to scale of our lives. For example, I have a guest post coming out tomorrow from Tom Engelhardt about the nature of the American Empire. Frankly, it’s more than disturbing. But, or should I write that as BUT, it is about matters that are trivial and inconsequential in the larger scheme of things.

All of which is a little introduction to a YouTube link that Suzann sent me; the video below. It’s just about 2 1/2 minutes long, yet is incredible. Plus it has already been watched over 9 million times!

Apologies for not being creative today!

What with spending too much time getting the new Apple set up, plus other domestic demands, I ran out of time to write a post for today.

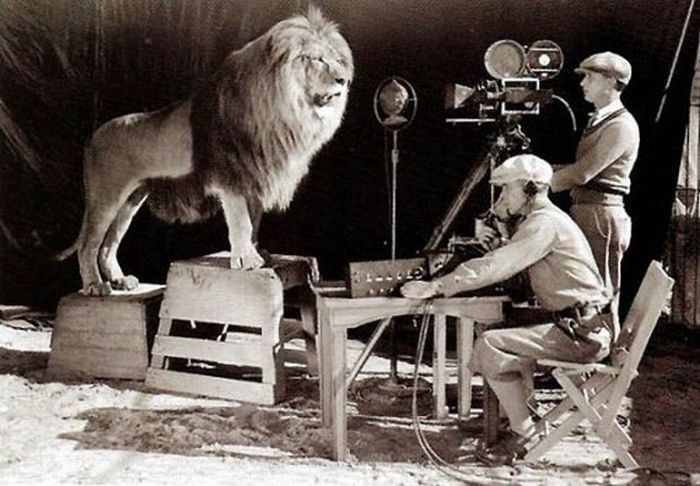

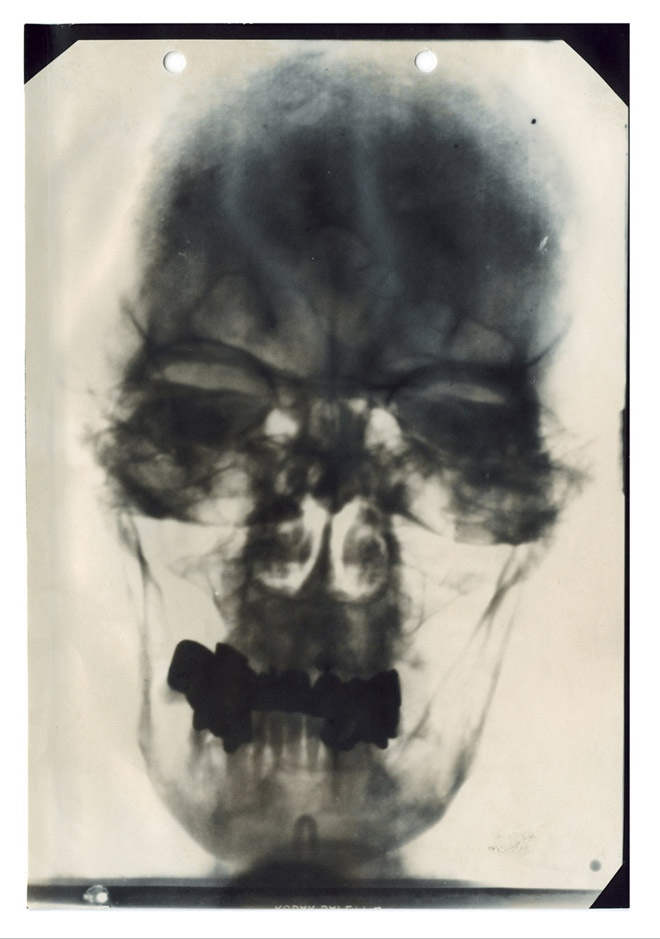

Dan Gomez recently forwarded me an email that contained an amazing collection of historical photographs.

So going to leave you with these.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

How time flies, eh!

A big move on in my computing.

Warning! Today’s post has almost nothing to do with dogs plus if you are not into computing then you may want to come back tomorrow! 😉

A little over a week ago I ordered an Apple Mac computer.

So what, I hear you say.

Well one way or another, I have been associated with personal computing for too many years and with the Microsoft Windows operating system equally for a long time.

Here’s that history and, be warned, I do go on a tad!

In 1970 I joined the Office Products (OP) Division of IBM in the United Kingdom. I joined as an office products salesman and after my initial training was based at IBM OP’s London North branch in Whetstone in the London Borough of Barnet. I loved both the job (remember the Selectric ‘Golfball’ typewriter?) and the company and conspired to win the prize of top UK salesman for the year 1977. By that time, IBM was selling dedicated word-processing (WP) machines. They offered powerful benefits for companies of many sizes and, as an experienced WP salesman, I was enjoying the fruits of that success. Thus it was that in 1978 I attended IBM’s Golden Circle celebrations for 1977 country winners from all around the world. The Golden Circle celebrations were held in Hawaii!

I returned from Hawaii with the clear idea in my mind that this was the time to move on; my ego didn’t like the idea of not being number one again! So within a couple of days of returning to my sales branch, I announced to my manager, David Halley, that I wished to give three months notice. I can still recall David’s rather shocked response with him saying, “But I always thought Golden Circle was an incentive event!”

In those days New Scientist magazine was a regular read for me. During my time of working out my notice I read in the magazine about this new personal computer from Commodore Business Machines that had been launched in the UK. It was called the Commodore PET (Personal Electronic Transactor) and had been unveiled in 1977 at the US West Coast Computer Faire. I was captivated by what I had read.

I had casually mentioned it to Richard Maugham; a good friend and fellow office-products salesman working for Olivetti UK. Richard said that coincidentally a close friend of many years had just been appointed sales manager for CBM UK Ltd. That friend was Keith Hall and on making contact with Keith, I was invited to go and meet him and learn more about this funny device. What I hadn’t bargained for was that Keith was yet another smart salesman; Keith and Richard had met when they were both salesmen working for Olivetti.

When I asked Keith the retail price of the ‘PET”, his immediate reply was, “Well why don’t you become a dealer and I can sell you one for 30% less!” Like most salesmen, I was always a sucker to a good sales pitch! I signed the necessary paperwork. (It is very sad to say that Keith died a few years ago, at far too young an age.)

So it was that towards the end of 1978, I became the sixth Commodore computer dealer in the UK, opening my small store in what had once been a Barber’s shop in Church Street, off Head Street in the centre of Colchester, Essex. I called my business Dataview Limited.

Frankly, I hadn’t a clue as to what I was doing! If it hadn’t been for a gigantic stroke of luck I would not have lasted long!

That piece of luck was meeting someone who was a programmer for a large, traditional computing company, ICL, who had bought himself a Commodore PET and, just out of fun, was writing a word-processing program. Now if I didn’t know about computers, personal or otherwise, I certainly knew about word-processing. When I looked at what Peter D. had written I practically wet myself. Because, I was looking at a program that even incomplete already offered three-quarters, give or take, of the functionality of a £20,000 IBM Word Processor.

I offered to guide Peter in refining and honing his software which he graciously accepted. Then a few weeks later Peter casually asked me if I would like to sell the software. I jumped at the opportunity and in due course Wordcraft was launched under the Dataview umbrella. (And do see my footnote!)

But back to my Windows journey.

In 1981 IBM announced the release of their own personal computer.

With my love affair with IBM not even dimmed, becoming an IBM PC dealer was a must. An IBM PC version of Wordcraft was developed by Peter and now things were really rocking and rolling. Then in 1983 Microsoft announced the development of Windows, a graphical user interface (GUI) for the operating system MS-DOS. MS-DOS was the existing operating system on the IBM PC.

By the time I sold Dataview in 1986, Windows was well on its way to evolving into a full personal computer operating system and ever since that time my own PCs have been Windows based. (Difficult to imagine now how in those early years Windows didn’t achieve any popularity!)

OK, fast forward 27 years to my present machine running Windows 7, Google Chrome web browser and all the fancy ‘cloud’-based applications of today.

Much of my time spent writing and blogging relies on me being online. Like so many others, as soon as I turn on my computer it becomes an online PC. On average, I am working in front of my PC for about 3 to 4 hours per day. However, slowly but surely over the past few months I have become aware of a number of strange occurrences, the most annoying of which is the regular ‘hanging’ of my Chrome browser. This was happening at least on a daily basis and required the complete rebooting of my PC – a right pain in the posterior!

Muttering about this to friends who know a lot more about computing than I, raised my awareness that the privacy and security of one’s computer was no longer to be assumed. Then just recently, I read online,

“A Special Surveillance Chip”

According to leaked internal documents from the German Federal Office for Security in Information Technology (BSI) that Die Zeit obtained, IT experts figured out that Windows 8, the touch-screen enabled, super-duper, but sales-challenged Microsoft operating system is outright dangerous for data security. It allows Microsoft to control the computer remotely through a built-in backdoor. Keys to that backdoor are likely accessible to the NSA – and in an unintended ironic twist, perhaps even to the Chinese.

The backdoor is called “Trusted Computing,” developed and promoted by the Trusted Computing Group, founded a decade ago by the all-American tech companies AMD, Cisco, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Intel, Microsoft, and Wave Systems. Its core element is a chip, the Trusted Platform Module (TPM), and an operating system designed for it, such as Windows 8. Trusted Computing Group has developed the specifications of how the chip and operating systems work together.

Its purpose is Digital Rights Management and computer security. The system decides what software had been legally obtained and would be allowed to run on the computer, and what software, such as illegal copies or viruses and Trojans, should be disabled. The whole process would be governed by Windows, and through remote access, by Microsoft.

Then a few paragraphs later:

It would be easy for Microsoft or chip manufacturers to pass the backdoor keys to the NSA and allow it to control those computers. NO, Microsoft would never do that, we protest. Alas, Microsoft, as we have learned from the constant flow of revelations, informs the US government of security holes in its products well before it issues fixes so that government agencies can take advantage of the holes and get what they’re looking for.

Now I’m using Windows 7 so imagine my angst when I then read:

Another document claims that Windows 8 with TPM 2.0 is “already” no longer usable. But Windows 7 can “be operated safely until 2020.” After that other solutions would have to be found for the IT systems of the Administration.

That did it for me – time to move on from Windows.

Many Apple-user friends said that I should switch to the Apple Mac; that it was the only logical way to go. I checked that all my important software applications that I used under Windows were compatible with the Apple Mac Operating System and thankfully they were. I was speaking of Open Office, WordPress, Scrivener, Picasa, Skype. Then I started to browse the Apple website. I was clear about wanting a desktop machine, an iMac, and pretty soon realised that my change of personal computing was going to cost me around $1,500, perhaps a little more.

Then Dan Gomez, both long-time friend and Apple user, in browsing the web came across the Mac mini. He called me and I took a look. For well under half the price of an iMac, I could get a great alternative to my Windows PC and use many of my existing peripherals.

A quick conversation with Zachary of the Apple Mac mini sales team and the deed was done! So all that remained was the great transition!

The box arrived last Wednesday.

I resisted opening the box until last Friday when I had some decent spare time.

Plugging it all together was easier than I feared.

Then the acid test. Could I even understand how to operate it? I put that off until Saturday!

I have to say that first impressions, especially of the elegance of the display and the icons, were great.

But this had to be a fully functional machine for me. Where to start? By downloading and installing the most critical of my software needs: Scrivener, my writing software.

Imagine my great pleasure and huge relief when less than a couple of hours later, not only had I downloaded and installed Scrivener for Apple Mac OS but had passed the latest backup file across from my Windows PC and accessed it on the Apple.

So, all in all, despite this being very early days, it’s starting to look like a great change.

However, I mustn’t close without thanking a few people:

Dan Gomez and John Hurlburt, friends and Apple users, and in John’s case experienced on both Windows and Apple systems. Guys, I couldn’t have made the decision to change without your kind, generous and supportive advice.

Zachary Brown of Apple sales, Mac mini team. Zach, I know it’s your job but nonetheless you did and said all the right things. (And the new screen is much better than my existing one!)

Last but not least, my dearest wife Jean, who just let me get on with things and even though I knew she didn’t have a clue as to what I kept muttering on about, never let on.

Footnote:

Earlier on I wrote about launching Wordcraft, the word-processing software for personal computers. That was in early 1979 and later that year I was invited to present Wordcraft at an international gathering of Commodore dealers held in Boston, Mass.

During my presentation, I used the word ‘fortnight’ unaware that Americans don’t know this common English word. Immediately, someone about 10 rows back in the audience called out, “Hey, Handover! What’s a fortnight?”

It released the presenter’s tension in me and I really hammed my response in saying, “Don’t be so silly, everybody knows the word fortnight.” Seem to remember asking the audience at large who else didn’t know the word. Of course, most raised their arms!

Now on a bit of a roll, I deliberately started using as many bizarre and archaic English words that came to me. Afterwards, the owner of the voice came introduced himself. He was Dan Gomez, a Californian based in Costa Mesa near Los Angeles and also involved in developing software for the Commodore.

Dan became my US West Coast distributor for Wordcraft and was very successful. When Dataview was sold, Dan and I continued to see each other regularly and I count him now as one of my dear friends. Through knowing Dan I got to know Dan’s sister Suzann and her husband Don. It was Su that invited me to spend Christmas 2007 with her and Don at their home in San Carlos, Mexico. Jean also lived in San Carlos and was close friends with Su. Together they had spent many years rescuing feral dogs from the streets of San Carlos and finding new homes for them.

Thus it was that I met Jean. Both Jean and I were born 20 miles apart in London!

So from ‘Hey, what’s a fortnight’ to living as happily as I have ever been in the rural countryside of Oregon. Funny old world!