Today it is all about jet contrails.

I just find the contrails of the jets way above us in Merlin, Oregon fascinating.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

All of the photos taken from our rear deck.

Plus two taken in September last year.

oooo

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Year: 2025

It is not as straightforward as I thought it was.

ooOOoo

Alex Jordan, University of Wisconsin-Stout

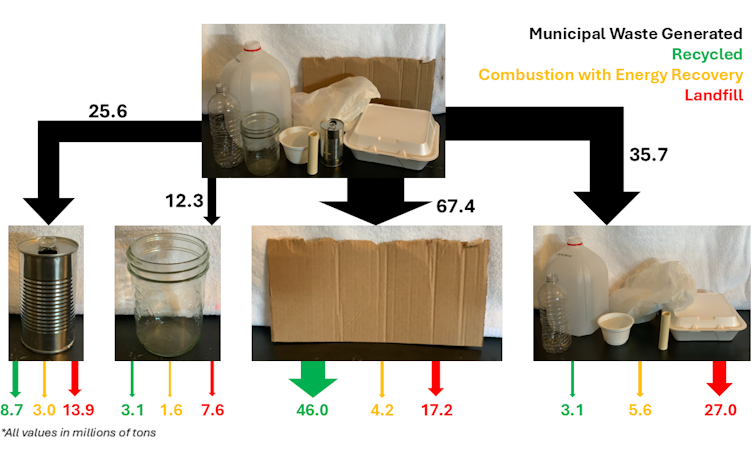

Every week, millions of Americans toss their recyclables into a single bin, trusting that their plastic bottles, aluminum cans and cardboard boxes will be given a new life.

But what really happens after the truck picks them up?

Single-stream recycling makes participating in recycling easy, but behind the scenes, complex sorting systems and contamination mean a large percentage of that material never gets a second life. Reports in recent years have found 15% to 25% of all the materials picked up from recycle bins ends up in landfills instead.

Plastics are among the biggest challenges. Only about 9% of the plastic generated in the U.S. actually gets recycled, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Some plastic is incinerated to produce energy, but most of the rest ends up in landfills instead.

So, what makes plastic recycling so difficult? As an engineer whose work focuses on reprocessing plastics, I have been exploring potential solutions.

In cities that use single-stream recycling, consumers put all of their recyclable materials − paper, cardboard, plastic, glass and metal − into a single bin. Once collected, the mixed recyclables are taken to a materials recovery facility, where they are sorted.

First, the mixed recyclables are shredded and crushed into smaller fragments, enabling more effective separation. The mixed fragments pass over rotating screens that remove cardboard and paper, allowing heavier materials, including plastics, metals and glass, to continue along the sorting line.

The basics of a single-stream recycling system in Pennsylvania. Source: Van Dyk Recycling Solutions.

Magnets are used to pick out ferrous metals, such as steel. A magnetic field that produces an electrical current with eddies sends nonferrous metals, such as aluminum, into a separate stream, leaving behind plastics and glass.

The glass fragments are removed from the remaining mix using gravity or vibrating screens.

That leaves plastics as the primary remaining material.

While single-stream recycling is convenient, it has downsides. Contamination, such as food residue, plastic bags and items that can’t be recycled, can degrade the quality of the remaining material, making it more difficult to reuse. That lowers its value.

Having to remove that contamination raises processing costs and can force recovery centers to reject entire batches.

Each recycling program has rules for which items it will and won’t take. You can check which items can and cannot be recycled for your specific program on your municipal page. Often, that means checking the recycling code stamped on the plastic next to the recycling icon.

These are the toughest plastics to recycle and most likely to be excluded in your local recycling program:

That leaves three plastics that can be recycled in many facilities:

However, these aren’t accepted in some facilities for reasons I’ll explain.

Some plastics can be chemically recycled or ground up for reprocessing, but not all plastics play well together.

Simple separation methods, such as placing ground-up plastics in water, can easily remove your soda bottle plastic (PET) from the mixture. The ground-up PET sinks in water due to the plastic’s density. However, HDPE, used in milk jugs, and PP, found in yogurt cups, both float, and they can’t be recycled together. So, more advanced and expensive technology, such as infrared spectroscopy, is often required to separate those two materials.

Once separated, the plastic from your soda bottle can be chemically recycled through a process called solvolysis.

It works like this: Plastic materials are formed from polymers. A polymer is a molecule with many repeating units, called monomers. Picture a pearl necklace. The individual pearls are the repeating monomer units. The string that runs through the pearls is the chemical bond that joins the monomer units together. The entire necklace can then be thought of as a single molecule.

During solvolysis, chemists break down that necklace by cutting the string holding the pearls together until they are individual pearls. Then, they string those pearls together again to create new necklaces.

Other chemical recycling methods, such as pyrolysis and gasification, have drawn environmental and health concerns because the plastic is heated, which can release toxic fumes. But chemical recycling also holds the potential to reduce both plastic waste and the need for new plastics, while generating energy.

The other two common types of recycled plastics − items such as yogurt cups (PP) and milk jugs (HDPE) − are like oil and water: Each can be recycled through reprocessing, but they don’t mix.

If polyethylene and polypropylene aren’t completely separated during recycling, the resulting mix can be brittle and generally unusable for creating new products.

Chemists are working on solutions that could increase the quality of recycled plastics through mechanical reprocessing, typically done at separate facilities.

One promising mechanical method for recycling mixed plastics is to incorporate a chemical called a compatibilizer. Compatibilizers contain the chemical structure of multiple different polymers in the same molecule. It’s like how lecithin, commonly found in egg yolks, can help mix oil and water to make mayonnaise − part of the lecithin molecule is in the oil phase and part is in the water phase.

In the case of yogurt cups and milk jugs, recently developed block copolymers are able to produce recycled plastic materials with the flexibility of polyethylene and the strength of polypropylene.

Research like this can make recycled materials more versatile and valuable and move products closer to a goal of a circular economy without waste.

However, improving recycling also requires better recycling habits.

You can help the recycling process by taking a few minutes to wash off food waste, avoiding putting plastic bags in your recycling bin and, importantly, paying attention to what can and cannot be recycled in your area.

Alex Jordan, Associate Professor of Plastics Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Stout

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

Can we all learn to be better at recycling in the face of so much world ‘news’!

A fascinating article!

I may be the wrong side of old but I still enjoy immensely the process of learning new things. Some of these new memories actually stay with me!

That is why it gives me great pleasure in republishing an article from The Conversation about our brains creating new memories.

ooOOoo

William Wright, University of California, San Diego and Takaki Komiyama, University of California, San Diego

Every day, people are constantly learning and forming new memories. When you pick up a new hobby, try a recipe a friend recommended or read the latest world news, your brain stores many of these memories for years or decades.

But how does your brain achieve this incredible feat?

In our newly published research in the journal Science, we have identified some of the “rules” the brain uses to learn.

The human brain is made up of billions of nerve cells. These neurons conduct electrical pulses that carry information, much like how computers use binary code to carry data.

These electrical pulses are communicated with other neurons through connections between them called synapses. Individual neurons have branching extensions known as dendrites that can receive thousands of electrical inputs from other cells. Dendrites transmit these inputs to the main body of the neuron, where it then integrates all these signals to generate its own electrical pulses.

It is the collective activity of these electrical pulses across specific groups of neurons that form the representations of different information and experiences within the brain.

For decades, neuroscientists have thought that the brain learns by changing how neurons are connected to one another. As new information and experiences alter how neurons communicate with each other and change their collective activity patterns, some synaptic connections are made stronger while others are made weaker. This process of synaptic plasticity is what produces representations of new information and experiences within your brain.

In order for your brain to produce the correct representations during learning, however, the right synaptic connections must undergo the right changes at the right time. The “rules” that your brain uses to select which synapses to change during learning – what neuroscientists call the credit assignment problem – have remained largely unclear.

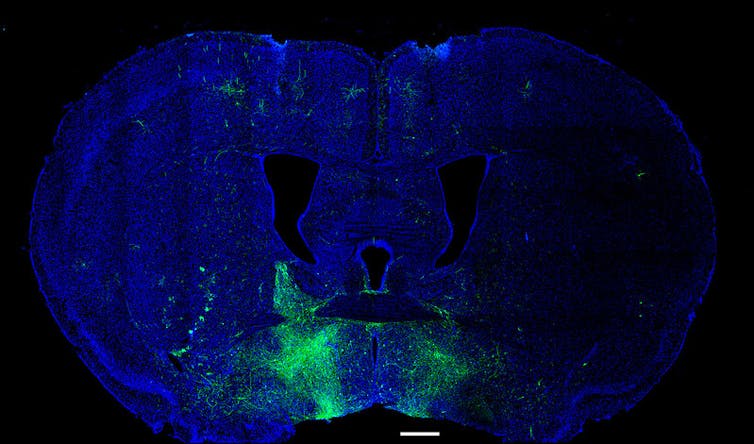

We decided to monitor the activity of individual synaptic connections within the brain during learning to see whether we could identify activity patterns that determine which connections would get stronger or weaker.

To do this, we genetically encoded biosensors in the neurons of mice that would light up in response to synaptic and neural activity. We monitored this activity in real time as the mice learned a task that involved pressing a lever to a certain position after a sound cue in order to receive water.

We were surprised to find that the synapses on a neuron don’t all follow the same rule. For example, scientists have often thought that neurons follow what are called Hebbian rules, where neurons that consistently fire together, wire together. Instead, we saw that synapses on different locations of dendrites of the same neuron followed different rules to determine whether connections got stronger or weaker. Some synapses adhered to the traditional Hebbian rule where neurons that consistently fire together strengthen their connections. Other synapses did something different and completely independent of the neuron’s activity.

Our findings suggest that neurons, by simultaneously using two different sets of rules for learning across different groups of synapses, rather than a single uniform rule, can more precisely tune the different types of inputs they receive to appropriately represent new information in the brain.

In other words, by following different rules in the process of learning, neurons can multitask and perform multiple functions in parallel.

This discovery provides a clearer understanding of how the connections between neurons change during learning. Given that most brain disorders, including degenerative and psychiatric conditions, involve some form of malfunctioning synapses, this has potentially important implications for human health and society.

For example, depression may develop from an excessive weakening of the synaptic connections within certain areas of the brain that make it harder to experience pleasure. By understanding how synaptic plasticity normally operates, scientists may be able to better understand what goes wrong in depression and then develop therapies to more effectively treat it.

These findings may also have implications for artificial intelligence. The artificial neural networks underlying AI have largely been inspired by how the brain works. However, the learning rules researchers use to update the connections within the networks and train the models are usually uniform and also not biologically plausible. Our research may provide insights into how to develop more biologically realistic AI models that are more efficient, have better performance, or both.

There is still a long way to go before we can use this information to develop new therapies for human brain disorders. While we found that synaptic connections on different groups of dendrites use different learning rules, we don’t know exactly why or how. In addition, while the ability of neurons to simultaneously use multiple learning methods increases their capacity to encode information, what other properties this may give them isn’t yet clear.

Future research will hopefully answer these questions and further our understanding of how the brain learns.

William Wright, Postdoctoral Scholar in Neurobiology, University of California, San Diego and Takaki Komiyama, Professor of Neurobiology, University of California, San Diego

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

Our human brains are incredible. Billions of nerve cells. Yet we are still getting to know the science of our brains and as that last sentence was written: “Future research will hopefully answer these questions and further our understanding of how the brain learns.”

Roll on this future research.