As promised, yet another set of photographs courtesy of Jess.

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

Beautiful photographs, and thank you, Jess! We especially loved the second one, yet they were all glorious.

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Year: 2024

An article from Live Science tells all.

Before I share the article with you, I felt I should mention that I haven’t found a link to share the Live Science item and it may need to be moved. We will see what happens.

ooOOoo

Dogs can smell their humans’ stress, and it makes them sad.

By Sara Novak, published July 27, 2024.

Dogs can smell when people are stressed, and it seems to make them feel downhearted.

Humans and dogs have been close companions for perhaps 30,000 years, according to anthropological and DNA evidence. So it would make sense that dogs would be uniquely qualified to interpret human emotion. They have evolved to read verbal and visual cues from their owners, and previous research has shown that with their acute sense of smell, they can even detect the odor of stress in human sweat. Now researchers have found that not only can dogs smell stress—in this case represented by higher levels of the hormone cortisol—they also react to it emotionally.

For the new study, published Monday in Scientific Reports, scientists at the University of Bristol in England recruited 18 dogs of varying breeds, along with their owners. Eleven volunteers who were unfamiliar to the dogs were put through a stress test involving public speaking and arithmetic while samples of their underarm sweat were gathered on pieces of cloth. Next, the human participants underwent a relaxation exercise that included watching a nature video on a beanbag chair under dim lighting, after which new sweat samples were taken. Sweat samples from three of these volunteers were used in the study.

Participating canines were put into three groups and smelled sweat samples from one of the three volunteers. Prior to doing so, the dogs were trained to know that a food bowl at one location contained a treat and that a bowl at another location did not. During testing, bowls that did not contain a treat were sometimes placed in one of three “ambiguous” locations. In one testing session, when the dogs smelled the sample from a stressed volunteer, compared with the scent of a cloth without a sample, they were less likely to approach the bowl in one of the ambiguous locations, suggesting that they thought this bowl did not contain a treat. Previous research has shown that an expectation of a negative outcome reflects a down mood in dogs.

The results imply that when dogs are around stressed individuals, they’re more pessimistic about uncertain situations, whereas proximity to people with the relaxed odor does not have this effect, says Zoe Parr-Cortes, lead study author and a Ph.D. student at Bristol Veterinary School at the University of Bristol. “For thousands of years, dogs have learned to live with us, and a lot of their evolution has been alongside us. Both humans and dogs are social animals, and there’s an emotional contagion between us,” she says. “Being able to sense stress from another member of the pack was likely beneficial because it alerted them of a threat that another member of the group had already detected.”

The fact that the odor came from an individual who was unfamiliar to the dogs speaks to the importance of smell for the animals and to the way it affects emotions in such practical situations, says Katherine A. Houpt, a professor emeritus of behavioral medicine at Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. Houpt, who was not involved in the new study, suggests that the smell of stress may have reduced the dogs’ hunger because it’s known to impact appetite. “It might not be that it’s changing their decision-making but more that it’s changing their motivation for food,” she says. “It makes sense because when you’re super stressed, you’re not quite as interested in that candy bar.”

This research, Houpt adds, shows that dogs have empathy based on smell in addition to visual and verbal cues. And when you’re stressed, that could translate into behaviors that your dog doesn’t normally display, she says. What’s more, it leaves us to wonder how stress impacts the animals under the more intense weight of an anxious owner. “If the dogs are responding to more mild stress like this, I’d be interested to see how they responded to something more serious like an impending tornado, losing your job or failing a test,” Houpt says. “One would expect the dog to be even more attuned to an actual threat.”

Sara Novak, Science Writer

Sara Novak is a science writer based on Sullivan’s Island, S.C. Her work has appeared in Discover, Sierra Magazine, Popular Science, New Scientist, and more. Follow Novak on X (formerly Twitter) @sarafnovak

ooOOoo

Dogs are such perfect animals and Sara brings this out so well. As was pointed out in the article dogs have learned to live with us humans over thousands of years.

Well done, Sara!

Beyond our imagination.

Until quite recently I had imagined that a tree was just a tree. Then Jean and I got to watch a YouTube video on trees and it blew our minds. Here is what we watched:

That led us on to watching Judi Dench’s video of trees:

Which is a longish introduction to a piece on The Conversation about trees.

ooOOoo

Delphine Farmer, Colorado State University and Mj Riches, Colorado State University

When wildfire smoke is in the air, doctors urge people to stay indoors to avoid breathing in harmful particles and gases. But what happens to trees and other plants that can’t escape from the smoke?

They respond a bit like us, it turns out: Some trees essentially shut their windows and doors and hold their breath.

As atmospheric and chemical scientists, we study the air quality and ecological effects of wildfire smoke and other pollutants. In a study that started quite by accident when smoke overwhelmed our research site in Colorado, we were able to watch in real time how the leaves of living pine trees responded.

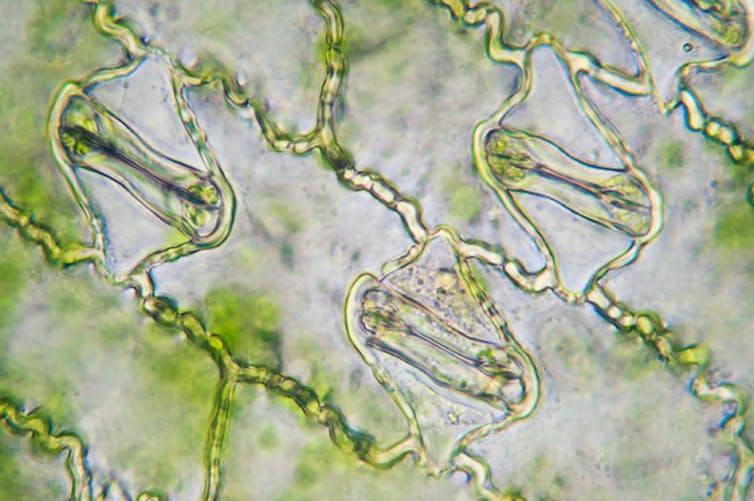

Plants have pores on the surface of their leaves called stomata. These pores are much like our mouths, except that while we inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, plants inhale carbon dioxide and exhale oxygen.

Both humans and plants inhale other chemicals in the air around them and exhale chemicals produced inside them – coffee breath for some people, pine scents for some trees.

Unlike humans, however, leaves breathe in and out at the same time, constantly taking in and releasing atmospheric gases.

In the early 1900s, scientists studying trees in heavily polluted areas discovered that those chronically exposed to pollution from coal-burning had black granules clogging the leaf pores through which plants breathe. They suspected that the substance in these granules was partly created by the trees, but due to the lack of available instruments at the time, the chemistry of those granules was never explored, nor were the effects on the plants’ photosynthesis.

Most modern research into wildfire smoke’s effects has focused on crops, and the results have been conflicting.

For example, a study of multiple crop and wetland sites in California showed that smoke scatters light in a way that made plants more efficient at photosynthesis and growth. However, a lab study in which plants were exposed to artificial smoke found that plant productivity dropped during and after smoke exposure – though those plants did recover after a few hours.

There are other clues that wildfire smoke can impact plants in negative ways. You may have even tasted one: When grapes are exposed to smoke, their wine can be tainted.

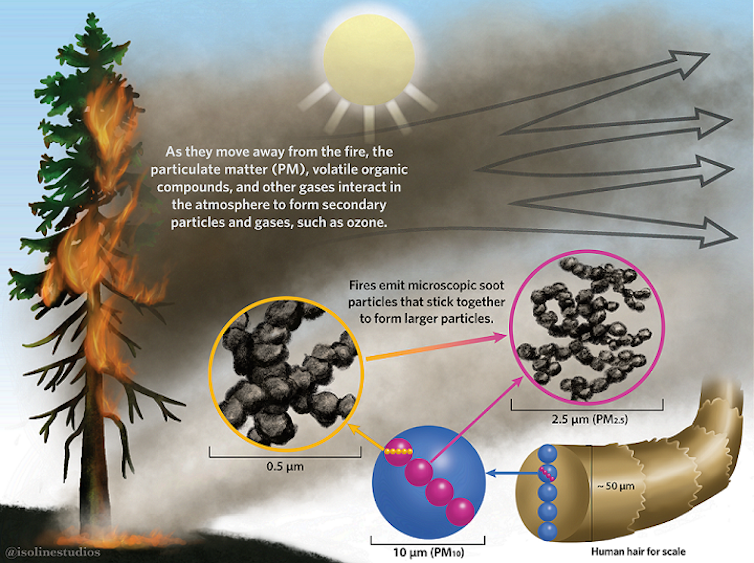

When wildfire smoke travels long distances, the smoke cooks in sunlight and chemically changes.

Mixing volatile organic compounds, nitrogen oxides and sunlight will make ground-level ozone, which can cause breathing problems in humans. It can also damage plants by degrading the leaf surface, oxidizing plant tissue and slowing photosynthesis.

While scientists usually think about urban regions as being large sources of ozone that effect crops downwind, wildfire smoke is an emerging concern. Other compounds, including nitrogen oxides, can also harm plants and reduce photosynthesis.

Taken together, studies suggest that wildfire smoke interacts with plants, but in poorly understood ways. This lack of research is driven by the fact that studying smoke effects on the leaves of living plants in the wild is hard: Wildfires are hard to predict, and it can be unsafe to be in smoky conditions.

We didn’t set out to study plant responses to wildfire smoke. Instead, we were trying to understand how plants emit volatile organic compounds – the chemicals that make forests smell like a forest, but also impact air quality and can even change clouds.

Fall 2020 was a bad season for wildfires in the western U.S., and thick smoke came through a field site where we were working in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado.

On the first morning of heavy smoke, we did our usual test to measure leaf-level photosynthesis of Ponderosa pines. We were surprised to discover that the tree’s pores were completely closed and photosynthesis was nearly zero.

We also measured the leaves’ emissions of their usual volatile organic compounds and found very low readings. This meant that the leaves weren’t “breathing” – they weren’t inhaling the carbon dioxide they need to grow and weren’t exhaling the chemicals they usually release.

With these unexpected results, we decided to try to force photosynthesis and see if we could “defibrillate” the leaf into its normal rhythm. By changing the leaf’s temperature and humidity, we cleared the leaf’s “airways” and saw a sudden improvement in photosynthesis and a burst of volatile organic compounds.

What our months of data told us is that some plants respond to heavy bouts of wildfire smoke by shutting down their exchange with outside air. They are effectively holding their breath, but not before they have been exposed to the smoke.

We hypothesize a few processes that could have caused leaves to close their pores: Smoke particles could coat the leaves, creating a layer that prevents the pores from opening. Smoke could also enter the leaves and clog their pores, keeping them sticky. Or the leaves could physically respond to the first signs of smoke and close their pores before they get the worst of it.

It’s likely a combination of these and other responses.

The jury is still out on exactly how long the effects of wildfire smoke last and how repeated smoke events will affect plants – including trees and crops – over the long term.

With wildfires increasing in severity and frequency due to climate change, forest management policies and human behavior, it’s important to gain a better understanding of the impact.

Delphine Farmer, Professor of Chemistry, Colorado State University and Mj Riches, Postdoctoral Researcher in Environmental and Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

The biggest tree in the world is reputed to be the General Sherman tree in California. Here is the introduction from WikiPedia:

General Sherman is a giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) tree located at an elevation of 2,109 m (6,919 ft) above sea level in the Giant Forest of Sequoia National Park in Tulare County, in the U.S. state of California. By volume, it is the largest known living single-stem tree on Earth.

Amazing!