Back to Unsplash!

I put in the search description ‘Service dogs’ but that didn’t seem to be the correct way of describing the search. Anyway, I liked what was seen!

ooOOoo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

There you are, good people!

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Year: 2023

Back to Unsplash!

I put in the search description ‘Service dogs’ but that didn’t seem to be the correct way of describing the search. Anyway, I liked what was seen!

ooOOoo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

oooo

There you are, good people!

A fascinating list!

Now I can’t recall where I saw these facts; I suspect they were emailed to me.

Whatever, it doesn’t matter, for they are amazing!

ooOOoo

1. Dogs have an incredible sense of smell—up to 100,000 times better than ours! They have more than 220 million olfactory receptors in their noses, while humans only have around 5 million.

2. Dogs can recognize up to 250 words and gestures, and they can even understand the tone of voice we use when we’re speaking to them.

3. Dogs can see in the dark better than us. They have a layer of cells in their eyes called the tapetum lucidum which reflects light back into the retina and helps them to see better in low light.

4. Dogs can sense when something is wrong or when you’re feeling down. They’ll often come and sit with you or give you extra cuddles when you’re feeling blue.

5. Dogs have an incredible sense of direction and can find their way back home from miles away. They use a combination of smell, sight and sound to remember the route they took.

6. Dogs can often tell when you’re about to sneeze. They have a special ability to sense subtle changes in our body language, and they can detect the slight changes that happen right before you sneeze.

7. Dogs can also tell when you’re happy or sad. They have the ability to sense changes in our breathing, body temperature, and even the amount of sweat we produce.

8. Dogs can sense when you’re getting sick. They can detect changes in your scent that you don’t even notice, and they’ll often come and comfort you when you’re feeling unwell.

9. Dogs can sense when someone is going to epileptic seizures or diabetic shock. They can detect the changes in smell, behavior and body chemistry that occur before a seizure or shock happens.

10. Dogs can detect certain types of cancer. They’re able to sniff out volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the breath, urine or sweat of a person with cancer, which is why some organizations are training dogs to use their noses to detect cancer in humans.

ooOOoo

Dogs are amazing animals, in so many ways!

A fascinating insight into recovered plastic.

Like so many others we do our little bit regarding plastic but do not properly think about the issue. I have to admit that I am not even sure if all plastics are harmful or just some.

But I comprehend art!

That is why I am republishing, with permission, this article from The Conversation.

ooOOoo

Pam Longobardi, Georgia State University

I am obsessed with plastic objects. I harvest them from the ocean for the stories they hold and to mitigate their ability to harm. Each object has the potential to be a message from the sea – a poem, a cipher, a metaphor, a warning.

My work collecting and photographing ocean plastic and turning it into art began with an epiphany in 2005, on a far-flung beach at the southern tip of the Big Island of Hawaii. At the edge of a black lava beach pounded by surf, I encountered multitudes upon multitudes of plastic objects that the angry ocean was vomiting onto the rocky shore.

I could see that somehow, impossibly, humans had permeated the ocean with plastic waste. Its alien presence was so enormous that it had reached this most isolated point of land in the immense Pacific Ocean. I felt I was witness to an unspeakable crime against nature, and needed to document it and bring back evidence.

I began cleaning the beach, hauling away weathered and misshapen plastic debris – known and unknown objects, hidden parts of a world of things I had never seen before, and enormous whalelike colored entanglements of nets and ropes.

I returned to that site again and again, gathering material evidence to study its volume and how it had been deposited, trying to understand the immensity it represented. In 2006, I formed the Drifters Project, a collaborative global entity to highlight these vagrant, translocational plastics and recruit others to investigate and mitigate ocean plastics’ impact.

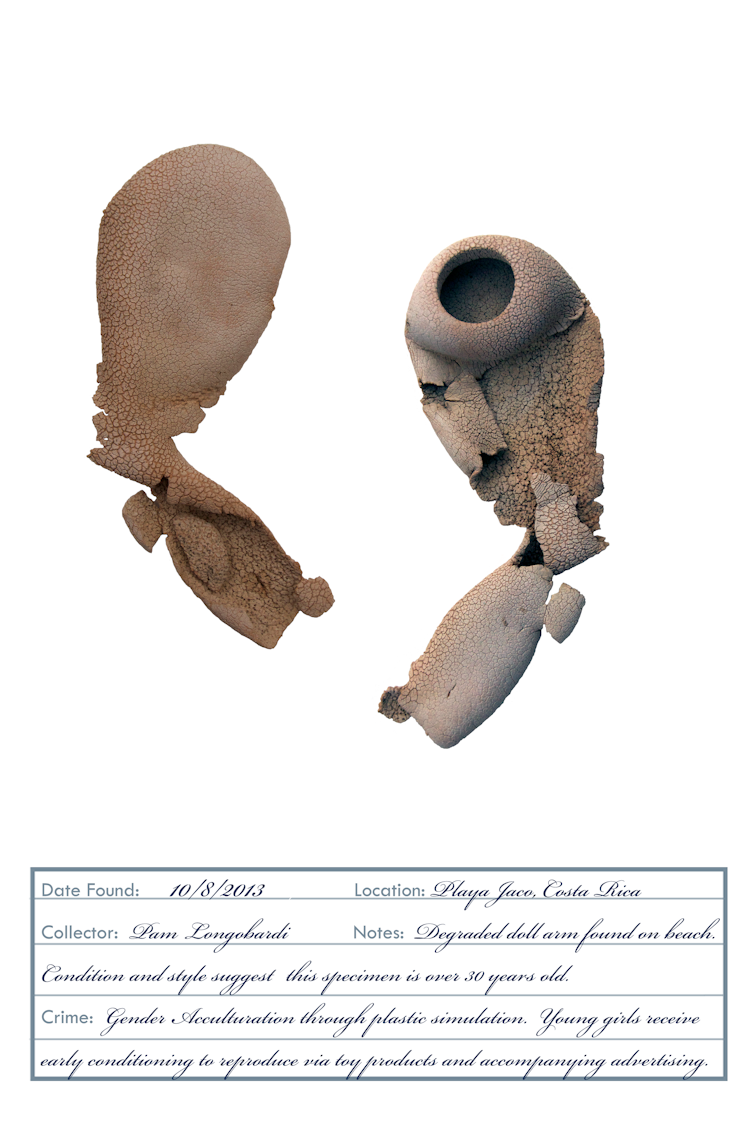

My new book, “Ocean Gleaning,” tracks 17 years of my art and research around the world through the Drifters Project. It reveals specimens of striking artifacts harvested from the sea – objects that once were utilitarian, but have been changed by their oceanic voyages and come back as messages from the ocean.

I grew up in what some now deem the age of plastic. Though it’s not the only modern material invention, plastic has had the most unforeseen consequences.

My father was a biochemist at the chemical company Union Carbide when I was a child in New Jersey. He played golf with an actor who portrayed “The Man from Glad,” a Get Smart-styled agent who rescued flustered housewives in TV commercials from inferior brands of plastic wrap that snarled and tangled. My father brought home souvenir pins of Union Carbide’s hexagonal logo, based on the carbon molecule, and figurine pencil holders of “TERGIE,” the company’s blobby turquoise mascot.

On the 2013 Gyre Expedition, Pam Longobardi traveled with a team of scientists, artists and policymakers to investigate and remove tons of oceanic plastic washing out of great gyres, or currents, in the Pacific Ocean, and make art from it.

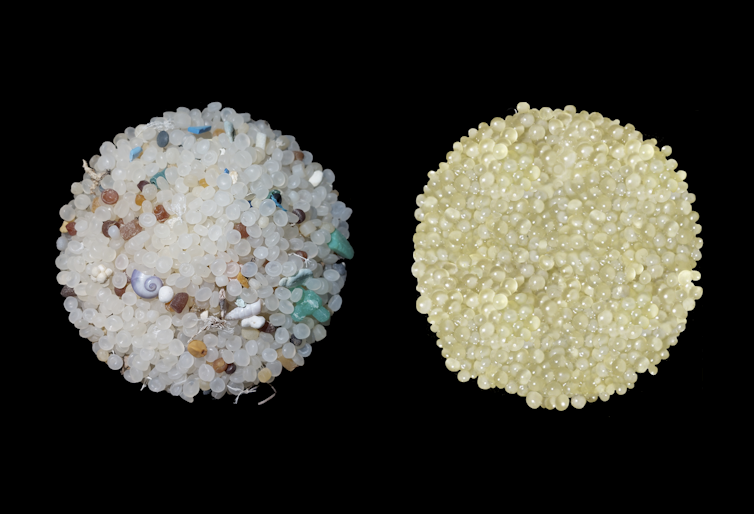

Today I see plastic as a zombie material that haunts the ocean. It is made from petroleum, the decayed and transformed life forms of the past. Drifting at sea, it “lives” again as it gathers a biological slime of algae and protozoans, which become attachment sites for larger organisms.

When seabirds, fish and sea turtles mistake this living encrustation for food and eat it, plastic and all, the chemical load lives on in their digestive tracts. Their body tissues absorb chemicals from the plastic, which remain undigested in their stomachs, often ultimately killing them.

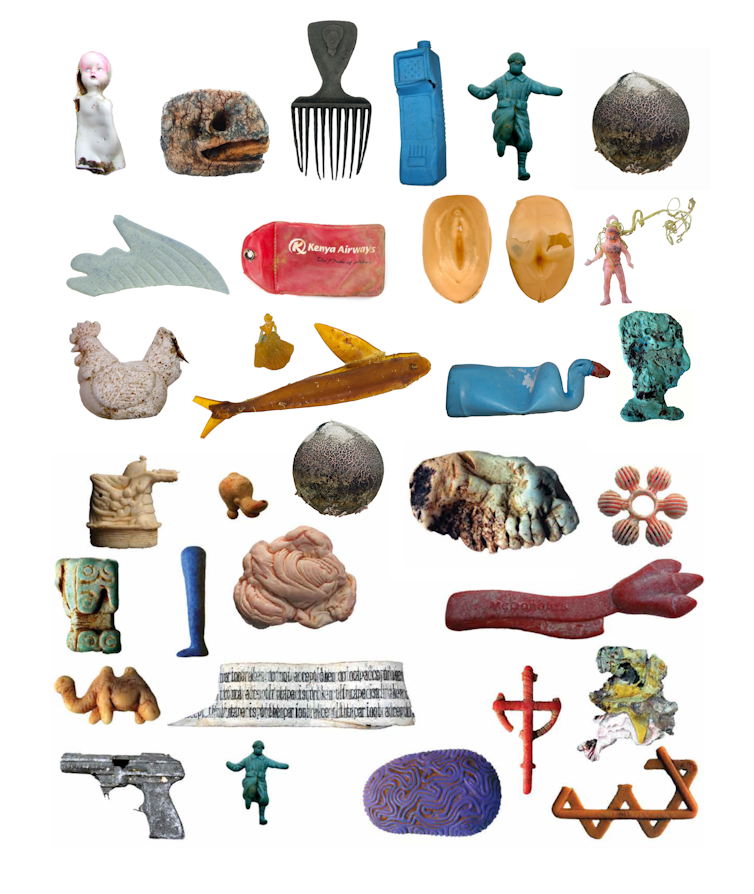

I see plastic objects as the cultural archaeology of our time – relics of global late-capitalist consumer society that mirror our desires, wishes, hubris and ingenuity. They become transformed as they leave the quotidian world and collide with nature. By regurgitating them ashore or jamming them into sea caves, the ocean is communicating with us through materials of our own making. Some seem eerily familiar; others are totally alien.

A person engaging in ocean gleaning acts as a detective and a beacon, hunting for the forensics of this crime against the natural world and shining the light of interrogation on it. By searching for ocean plastic in a state of open receptiveness, a gleaner like me can find symbols of pop culture, religion, war, humor, irony and sorrow.

In keeping with the drifting journeys of these material artifacts, I prefer using them in a transitive form as installations. All of these works can be dismantled and reconfigured, although plastic materials are nearly impossible to recycle. I display some objects as specimens on steel pins, and wire others together to form large-scale sculptures.

I am interested in ocean plastic in particular because of what it reveals about us as humans in a global culture, and about the ocean as a cultural space and a giant dynamic engine of life and change. Because ocean plastic visibly shows nature’s attempts to reabsorb and regurgitate it, it has profound stories to tell.

I believe humankind is at a crossroads with regards to the future. The ocean is asking us to pay attention. Paying attention is an act of giving, and in the case of plastic pollution, it is also an act of taking: Taking plastic out of your daily life. Taking plastic out of the environment. And taking, and spreading, the message that the ocean is laying out before our eyes.

Pam Longobardi, Regents’ Professor of Art and Design, Georgia State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

Pam at one point describes the ocean plastic”… because of what it reveals about us as humans in a global culture, and about the ocean as a cultural space and a giant dynamic engine of life and change …”. It raises questions that I can only ponder the answer. Ultimately, are there too many inhabitants on this planet? What does the next generation think? Is there an answer?