The Einstein-Freud Letters

I was born in London in November, 1944. Exactly six months before the Second World War ended in April, 1945.

Thus it was of great interest to me that yesterday Jean and I listened to a BBC Radio 4 programme about the letters that were exchanged between two great Jewish men: Einstein and Freud, in 1932. The programme was called Why War? The Einstein-Freud Letters.

The programme ends with offering the listener a fundamental choice, which I won’t spoil for you now. But to me it is an extension of my post (or Patrice’s post) that I published recently on March 19th.

I believe, and hope, you can listen to it by clicking on this link. Here also is the text that is at that link:

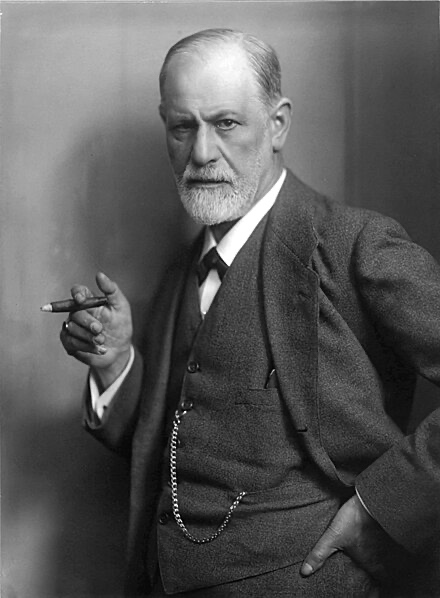

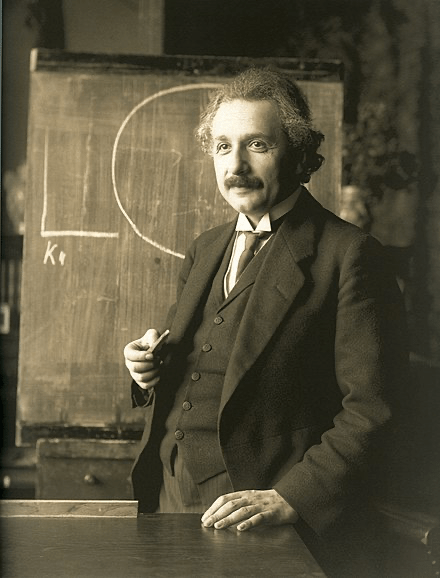

In 1932 the world-famous physicist Albert Einstein wrote a public letter to the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud. Einstein, a keen advocate of the League of Nations and peace campaigner, asked Freud if he thought war and aggression was forever tied to human psychology and the course of international relations: could we ever secure a lasting world peace?

Einstein’s letter is deeply prescient, as is Freud’s extraordinary response. The exchange was titled ‘Why War?’. The two thinkers explore the nature of war and peace in politics and in all human life; they think about human nature, the history of warfare and human aggression and the hope represented by the foundation of the League of Nations (precursor to the UN) and its promise of global security and a new architecture of international law.

At the time of their exchange, Freud is in the last great phase of his career and has already introduced psychoanalysis into the field of politics and society. Einstein, the younger of the two, is using his huge international profile as a physicist for political and pacifist intervention.

For Einstein, future world security means a shared moral understanding across the global order – that humankind rise above the ‘state of nature’ never to devolve into total war again. He wrote to Freud, as ‘a citizen of the world…immune to nationalist bias…I greatly admire your passion to ascertain the truth. You have shown how the aggressive and destructive instincts are bound up in the human psyche with those of love and the lust for life. At the same time, you make manifest your devotion to the goal of liberation from the evils of war…’ Is it possible, Einstein asks Freud, to make us ‘proof against the psychoses of hate and destructiveness?’. Freud’s answer is fascinating and quite unexpected.

The exchange of letters was sponsored by the International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation, an organisation promoting global security by using prominent thinkers, drawing on multiple fields of knowledge (from science to psychology, politics and law) to achieve a new language for international peace, following the lessons learned from the Great War of 1914-18.

But even as Einstein wrote to Freud in the summer of 1932, the Nazi party became the largest political party in the German Reichstag. Both men felt a sense of apprehension about what was coming; both were pacifist, both Jewish, both would be driven into exile (both Einsteinian physics and Freudian psychoanalysis were denounced by the new regime). The letters were finally published in 1933 when Hitler came to power, suppressed in Germany, and as a result never achieved the circulation intended for them.

Featuring readings from the Einstein–Freud letters and contributions from historians of warfare and psychoanalysis, war journalism and global security, this feature showcases the little-known exchange between two of the 20th century’s greatest thinkers, ‘Why War?’ – a question just as relevant in today’s world.

Contributors include historian of war and peace Margaret MacMillan, BBC chief international correspondent Lyse Doucet, defence and security expert Mark Galeotti, historian of international relations Patrick O Cohrs, author Lisa Appignanesi, who has written on Freud and the history of psychoanalysis, and Faisal Devji, historian of conflict and political violence in India and the Middle East.

Readings are by Elliot Levey (Einstein) and Henry Goodman (Freud)

Produced by Simon Hollis

A Brook Lapping production for BBC Radio 4

Albert Einstein

Sigmund Freud

Freud, 1921

Two very great men.