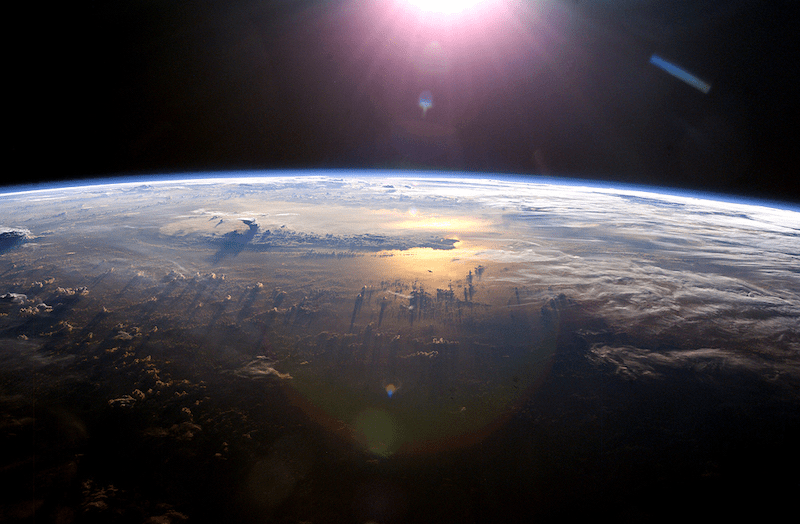

Pondering on space.

Like so many people, I am fascinated by the universe. Just our own universe is staggering. Here are some items published on the NASA website.

Solar System Facts

Our solar system includes the Sun, eight planets, five officially named dwarf planets, hundreds of moons, and thousands of asteroids and comets.

Our solar system is located in the Milky Way, a barred spiral galaxy with two major arms, and two minor arms. Our Sun is in a small, partial arm of the Milky Way called the Orion Arm, or Orion Spur, between the Sagittarius and Perseus arms. Our solar system orbits the center of the galaxy at about 515,000 mph (828,000 kph). It takes about 230 million years to complete one orbit around the galactic center.

Now to the centre of our universe. And it give me pleasure to republish this account.

ooOOoo

Where is the center of the universe?

Rob Coyne, University of Rhode Island

About a century ago, scientists were struggling to reconcile what seemed a contradiction in Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

Published in 1915, and already widely accepted worldwide by physicists and mathematicians, the theory assumed the universe was static – unchanging, unmoving and immutable. In short, Einstein believed the size and shape of the universe today was, more or less, the same size and shape it had always been.

But when astronomers looked into the night sky at faraway galaxies with powerful telescopes, they saw hints the universe was anything but that. These new observations suggested the opposite – that it was, instead, expanding.

Scientists soon realized Einstein’s theory didn’t actually say the universe had to be static; the theory could support an expanding universe as well. Indeed, by using the same mathematical tools provided by Einstein’s theory, scientists created new models that showed the universe was, in fact, dynamic and evolving.

I’ve spent decades trying to understand general relativity, including in my current job as a physics professor teaching courses on the subject. I know wrapping your head around the idea of an ever-expanding universe can feel daunting – and part of the challenge is overriding your natural intuition about how things work. For instance, it’s hard to imagine something as big as the universe not having a center at all, but physics says that’s the reality.

The universe gets bigger every day.

The space between galaxies

First, let’s define what’s meant by “expansion.” On Earth, “expanding” means something is getting bigger. And in regard to the universe, that’s true, sort of. Expansion might also mean “everything is getting farther from us,” which is also true with regard to the universe. Point a telescope at distant galaxies and they all do appear to be moving away from us.

What’s more, the farther away they are, the faster they appear to be moving. Those galaxies also seem to be moving away from each other. So it’s more accurate to say that everything in the universe is getting farther away from everything else, all at once.

This idea is subtle but critical. It’s easy to think about the creation of the universe like exploding fireworks: Start with a big bang, and then all the galaxies in the universe fly out in all directions from some central point.

But that analogy isn’t correct. Not only does it falsely imply that the expansion of the universe started from a single spot, which it didn’t, but it also suggests that the galaxies are the things that are moving, which isn’t entirely accurate.

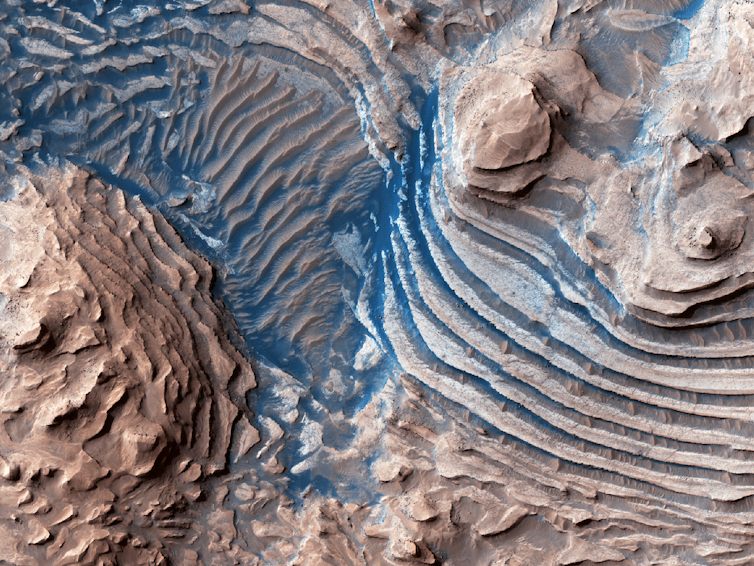

It’s not so much the galaxies that are moving away from each other – it’s the space between galaxies, the fabric of the universe itself, that’s ever-expanding as time goes on. In other words, it’s not really the galaxies themselves that are moving through the universe; it’s more that the universe itself is carrying them farther away as it expands.

A common analogy is to imagine sticking some dots on the surface of a balloon. As you blow air into the balloon, it expands. Because the dots are stuck on the surface of the balloon, they get farther apart. Though they may appear to move, the dots actually stay exactly where you put them, and the distance between them gets bigger simply by virtue of the balloon’s expansion.

Now think of the dots as galaxies and the balloon as the fabric of the universe, and you begin to get the picture.

Unfortunately, while this analogy is a good start, it doesn’t get the details quite right either.

The 4th dimension

Important to any analogy is an understanding of its limitations. Some flaws are obvious: A balloon is small enough to fit in your hand – not so the universe. Another flaw is more subtle. The balloon has two parts: its latex surface and its air-filled interior.

These two parts of the balloon are described differently in the language of mathematics. The balloon’s surface is two-dimensional. If you were walking around on it, you could move forward, backward, left, or right, but you couldn’t move up or down without leaving the surface.

Now it might sound like we’re naming four directions here – forward, backward, left and right – but those are just movements along two basic paths: side to side and front to back. That’s what makes the surface two-dimensional – length and width.

The inside of the balloon, on the other hand, is three-dimensional, so you’d be able to move freely in any direction, including up or down – length, width and height.

This is where the confusion lies. The thing we think of as the “center” of the balloon is a point somewhere in its interior, in the air-filled space beneath the surface.

But in this analogy, the universe is more like the latex surface of the balloon. The balloon’s air-filled interior has no counterpart in our universe, so we can’t use that part of the analogy – only the surface matters.

So asking, “Where’s the center of the universe?” is somewhat like asking, “Where’s the center of the balloon’s surface?” There simply isn’t one. You could travel along the surface of the balloon in any direction, for as long as you like, and you’d never once reach a place you could call its center because you’d never actually leave the surface.

In the same way, you could travel in any direction in the universe and would never find its center because, much like the surface of the balloon, it simply doesn’t have one.

Part of the reason this can be so challenging to comprehend is because of the way the universe is described in the language of mathematics. The surface of the balloon has two dimensions, and the balloon’s interior has three, but the universe exists in four dimensions. Because it’s not just about how things move in space, but how they move in time.

Our brains are wired to think about space and time separately. But in the universe, they’re interwoven into a single fabric, called “space-time.” That unification changes the way the universe works relative to what our intuition expects.

And this explanation doesn’t even begin to answer the question of how something can be expanding indefinitely – scientists are still trying to puzzle out what powers this expansion.

So in asking about the center of the universe, we’re confronting the limits of our intuition. The answer we find – everything, expanding everywhere, all at once – is a glimpse of just how strange and beautiful our universe is.

Rob Coyne, Teaching Professor of Physics, University of Rhode Island

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

That last paragraph says it all: ‘So in asking about the center of the universe, we’re confronting the limits of our intuition.’

Just wonderful!