Back to Unsplash.

oooo

oooo

oooo

Folks, that’s all for today!

Dogs are animals of integrity. We have much to learn from them.

Year: 2025

Back to Unsplash.

oooo

oooo

oooo

Folks, that’s all for today!

A riveting article from George Monbiot.

George Monbiot published an article in The Guardian recently that was as hard-hitting as I have ever read from him.

I found it very powerful even though I have not been living in England since 2008. Mr Monbiot has previously given me permission to republish his articles and here it is.

ooOOoo

Posted on 3rd June 2025

Keir Starmer has accidentally given us four years in which to build a new political system. We should seize the chance.

By George Monbiot, published in the Guardian 27th May 2025

This feels terminal. The breaches of trust have been so frequent, so vast and so decisive that the voters Labour has already lost are unlikely to return. In one forum after another, I hear the same sentiments: “I voted for change, not the same or worse.” “I’ve voted Labour all my life, but that’s it for me.” “I feel I’ve been had.”

It’s not dissatisfaction. It’s not disillusionment. It’s revulsion: visceral fury, anger on a level I’ve seldom seen before, even towards Tory cruelties. Why? Because these are Tory cruelties, delivered by a party that claimed to be the only alternative, in our first-past-the-post electoral system.

Everyone can name at least some of the betrayals:

cutting disability benefits; supplying weapons and, allegedly, intelligence to the Israeli government as it pursues genocide in Gaza; channelling Reform UK and Enoch Powell in maligning immigrants; slashing international aid; trashing wildlife and habitats while insulting and abusing people who want to protect them; announcing yet another draconian anti-protest law; leaving trans people in legal limbo; rigidly adhering to outdated and socially destructive fiscal rules; imposing further austerity on government departments and public services. Once the great hope of the oppressed, Labour has become the oppressor.

Like many people, I was wary of Keir Starmer. I had limited expectations, but I willed Labour to succeed. So I’ve watched aghast as he and his inner circle have squandered one of the greatest opportunities the party has ever been granted. They seem to despise people who voted for them, while courting and flattering those who didn’t and won’t.

The results? Last week, the polling company Thinks Insight & Strategy found that 52% of those who voted Labour in the 2024 general election are considering switching to the Liberal Democrats or the Greens. That’s more than twice as many as might migrate to Reform UK. The research group Persuasion UK estimates that Labour could lose 250 seatsas a result of this flight to more progressive parties (again, more than twice as many as it could lose through voters shifting to Reform). Figures compiled by the progressive thinktank Compass show that Labour would lose its majority on just a 6% swing. Already, while it won a massive majority on a measly 34% vote at the election, it now polls at just 22%.

Labour’s strategy is incomprehensible. Experience from the rest of Europe shows that when centrist parties adopt far-right rhetoric and policies, they empower the far right while shedding their own supporters.

What explains this idiocy? Labour has succumbed, quickly and hard, to the defining sickness of our undemocratic political system: the sofa cabinet system of close advisers. Opaque and unaccountable government favours opaque and unaccountable power. Ever receptive to the demands of rentiers, oligarchs, non-doms and corporations, Labour’s oh-so-clever strategists are moronically giftwrapping the country for Nigel Farage.

Governments don’t start conservative and turn radical. The cruelty will set like concrete. The likely result is annihilation in 2029. On this trajectory, it might not be surprising if Labour were left with seats in only double figures.

Perhaps it’s a blessing that Starmer has shown his hand so soon, as we now have four years in which to prepare. I’m not a party person: for me, it’s a question of what works. And now we can clearly see the shape of it.

The Compass analysis, published in December, reveals extreme electoral volatility. This is caused by a combination of public fury towards austerity, exclusion, rip-off rents and startlingly low rates of wellbeing, and the “democratic mayhem” resulting from a first-past-the-post system in which five parties are now polling at 10% or more. Small vote shifts in this situation can cause wild fluctuations in the allocation of seats.

The report points out that the UK is an overwhelmingly progressive nation: in all but one election since 1979 most voters have supported left or centre-left parties. Of 15 nations surveyed, the UK has the extraordinary distinction of being both the furthest to the left and the most consistent elector of rightwing governments. Why? Because of our first-past-the-post system, which is grossly unfair not by accident but by design. Labour refuses to change it, as it wants to rule alone. The result is that most of the time it doesn’t rule at all.

The thinktank was hoping to mobilise the progressive majority around a revitalised Labour party, but that moment has passed. What the figures show, however, is massive potential for more radical change. A YouGov survey reveals that almost twice as many people want proportional representation in this country as those who wish to preserve the current system. So let’s build a government of parties that will introduce it.

Here’s the strategy. Join the Lib Dems, Greens, SNP or Plaid Cymru. As their numbers rise, other voters will see the tide turning. Encourage troubled Labour MPs to defect. Most importantly, begin the process in each constituency of bringing alienated voters together around a single candidate. This is what we did before the last election in South Devon, where polls had shown the anti-Tory vote evenly split between Labour and the Lib Dems. Through the People’s Primary designed by locals, the constituency decided to back the Lib Dems. The proof of the method can be seen less in the spectacular routing of the Conservatives (as similar upsets occurred elsewhere) than in the collapse in Labour’s numbers, which fell from 17% in 2019, and 26% in a poll before the primary began, to 6% in the 2024 election. The voters took back control, with startling results.

Whether you fully support any of these parties is beside the point. This coalition would break for ever the lesser-of-two-evils choice that Starmer has so cruelly abused, and which has for so long poisoned politics in this country. Game the system once and we’ll never have to game it again.

No longer will we be held hostage, no longer represented by people who hate us. It will be a tragedy if, as seems likely, Keir Starmer has destroyed the Labour party as a major political force. But it will be a blessing if he has also destroyed the two-party system.

ooOOoo

Proportional representation is explained in detail here. There is also an explanation on WikiPedia here. From which I quote a small section:

Proportional representation (PR) refers to any electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to political divisions (political parties) among voters. The aim of such systems is that all votes cast contribute to the result so that each representative in an assembly is mandated by a roughly equal number of voters, and therefore all votes have equal weight. Under other election systems, a bare plurality or a scant majority in a district are all that are used to elect a member or group of members. PR systems provide balanced representation to different factions, usually defined by parties, reflecting how votes were cast. Where only a choice of parties is allowed, the seats are allocated to parties in proportion to the vote tally or vote share each party receives.

That is a timely and powerful article from George Monbiot.

A YouTube video.

When my son, Alex, and Lisa, were with us in the second half of last month, they spoke of the tremendous joy they experienced in visiting Yellowstone before they came to us.

What a fabulous memory!

We are talking of prime numbers.

Science and mathematics have been a long interest of mine and I regret that I did not go to university to study science. But that was a long time ago!

However, thanks to The Conversation I can write about mathematics, in this case Prime Numbers.

ooOOoo

Jeremiah Bartz, University of North Dakota

A shard of smooth bone etched with irregular marks dating back 20,000 years puzzled archaeologists until they noticed something unique – the etchings, lines like tally marks, may have represented prime numbers. Similarly, a clay tablet from 1800 B.C.E. inscribed with Babylonian numbers describes a number system built on prime numbers.

As the Ishango bone, the Plimpton 322 tablet and other artifacts throughout history display, prime numbers have fascinated and captivated people throughout history. Today, prime numbers and their properties are studied in number theory, a branch of mathematics and active area of research today.

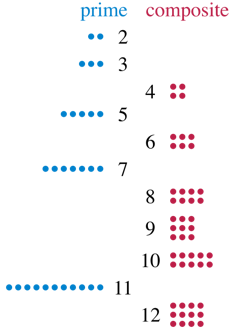

Informally, a positive counting number larger than one is prime if that number of dots can be arranged only into a rectangular array with one column or one row. For example, 11 is a prime number since 11 dots form only rectangular arrays of sizes 1 by 11 and 11 by 1. Conversely, 12 is not prime since you can use 12 dots to make an array of 3 by 4 dots, with multiple rows and multiple columns. Math textbooks define a prime number as a whole number greater than one whose only positive divisors are only 1 and itself.

Math historian Peter S. Rudman suggests that Greek mathematicians were likely the first to understand the concept of prime numbers, around 500 B.C.E.

Around 300 B.C.E., the Greek mathematician and logician Euler proved that there are infinitely many prime numbers. Euler began by assuming that there is a finite number of primes. Then he came up with a prime that was not on the original list to create a contradiction. Since a fundamental principle of mathematics is being logically consistent with no contradictions, Euler then concluded that his original assumption must be false. So, there are infinitely many primes.

The argument established the existence of infinitely many primes, however it was not particularly constructive. Euler had no efficient method to list all the primes in an ascending list.

In the middle ages, Arab mathematicians advanced the Greeks’ theory of prime numbers, referred to as hasam numbers during this time. The Persian mathematician Kamal al-Din al-Farisi formulated the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, which states that any positive integer larger than one can be expressed uniquely as a product of primes.

From this view, prime numbers are the basic building blocks for constructing any positive whole number using multiplication – akin to atoms combining to make molecules in chemistry.

Prime numbers can be sorted into different types. In 1202, Leonardo Fibonacci introduced in his book “Liber Abaci: Book of Calculation” prime numbers of the form (2p – 1) where p is also prime.

Today, primes in this form are called Mersenne primes after the French monk Marin Mersenne. Many of the largest known primes follow this format.

Several early mathematicians believed that a number of the form (2p – 1) is prime whenever p is prime. But in 1536, mathematician Hudalricus Regius noticed that 11 is prime but not (211 – 1), which equals 2047. The number 2047 can be expressed as 11 times 89, disproving the conjecture.

While not always true, number theorists realized that the (2p – 1) shortcut often produces primes and gives a systematic way to search for large primes.

The number (2p – 1) is much larger relative to the value of p and provides opportunities to identify large primes.

When the number (2p – 1) becomes sufficiently large, it is much harder to check whether (2p – 1) is prime – that is, if (2p – 1) dots can be arranged only into a rectangular array with one column or one row.

Fortunately, Édouard Lucas developed a prime number test in 1878, later proved by Derrick Henry Lehmer in 1930. Their work resulted in an efficient algorithm for evaluating potential Mersenne primes. Using this algorithm with hand computations on paper, Lucas showed in 1876 that the 39-digit number (2127 – 1) equals 170,141,183,460,469,231,731,687,303,715,884,105,727, and that value is prime.

Also known as M127, this number remains the largest prime verified by hand computations. It held the record for largest known prime for 75 years.

Researchers began using computers in the 1950s, and the pace of discovering new large primes increased. In 1952, Raphael M. Robinson identified five new Mersenne primes using a Standard Western Automatic Computer to carry out the Lucas-Lehmer prime number tests.

As computers improved, the list of Mersenne primes grew, especially with the Cray supercomputer’s arrival in 1964. Although there are infinitely many primes, researchers are unsure how many fit the type (2p – 1) and are Mersenne primes.

By the early 1980s, researchers had accumulated enough data to confidently believe that infinitely many Mersenne primes exist. They could even guess how often these prime numbers appear, on average. Mathematicians have not found proof so far, but new data continues to support these guesses.

George Woltman, a computer scientist, founded the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search, or GIMPS, in 1996. Through this collaborative program, anyone can download freely available software from the GIMPS website to search for Mersenne prime numbers on their personal computers. The website contains specific instructions on how to participate.

GIMPS has now identified 18 Mersenne primes, primarily on personal computers using Intel chips. The program averages a new discovery about every one to two years.

Luke Durant, a retired programmer, discovered the current record for the largest known prime, (2136,279,841 – 1), in October 2024.

Referred to as M136279841, this 41,024,320-digit number was the 52nd Mersenne prime identified and was found by running GIMPS on a publicly available cloud-based computing network.

This network used Nvidia chips and ran across 17 countries and 24 data centers. These advanced chips provide faster computing by handling thousands of calculations simultaneously. The result is shorter run times for algorithms such as prime number testing.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation is a civil liberty group that offers cash prizes for identifying large primes. It awarded prizes in 2000 and 2009 for the first verified 1 million-digit and 10 million-digit prime numbers.

Large prime number enthusiasts’ next two challenges are to identify the first 100 million-digit and 1 billion-digit primes. EFF prizes of US$150,000 and $250,000, respectively, await the first successful individual or group.

Eight of the 10 largest known prime numbers are Mersenne primes, so GIMPS and cloud computing are poised to play a prominent role in the search for record-breaking large prime numbers.

Large prime numbers have a vital role in many encryption methods in cybersecurity, so every internet user stands to benefit from the search for large prime numbers. These searches help keep digital communications and sensitive information safe.

Jeremiah Bartz, Associate Professor of Mathematics, University of North Dakota

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ooOOoo

I find it unbelievable that there are prizes for the first 100 million-digit prime number and also the first 1 billion-digit prime number. It is so far away from my understanding of these numbers that all I can say is: I find it unbelievable!